(267) 08-27-2022-to-09-02-2022__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(268) 09-03-2022-to-09-09-2022__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(269) 09-10-2022-to-09-16-2022__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

=======================================================

ALERT - RUSSIA INVADES UKRAINE - Consolidated Thread

Dr. Mark P. Barry @DrMarkPBarry 12m It's possible Putin's restraint in not escalating the war in Ukraine is because he knows he risks losing even China's tacit support. If Putin escalates, he throws China under the bus; and Xi could respond by isolating Russia. Who knows what was privately...

CHAT - Since it looks like Russia's military may be a paper tiger...

Unlike almost all the other countries on this planet.....our only saving grace is the guns we have behind EVERY BLADE OF GRASS!! And....GOD of course. :sal: the chinese have 3 guns behind every blade of grass. i don't remember where i read this, maybe here. the chinese aren't shipping much...

WAR - BREAKING NEWS HEAVY FIGHTING in KHERSON Ukraine Russians Fleeing City - LIVE

An apparent live feed, BREAKING NEWS HEAVY FIGHTING in KHERSON Ukraine Russians Fleeing City View: https://youtu.be/SvGe7rhtfvc

WAR - Ukraine's Top General Doesn't Rule Out "Limited" Nuclear War

...there's probably no such thing, really. Fair use cited so on and so forth. https://www.zerohedge.com/geopolitical/ukraines-top-general-doesnt-rule-out-limited-nuclear-war Ukraine's Top General Doesn't Rule Out "Limited" Nuclear War by Tyler Durden Friday, Sep 09, 2022 - 06:55 AM...

WAR - The Kharkov game changer - Pepe Escobar

Sept 13th 2022 This is an existential war. A do or die affair, Pepe Escobar writes. Wars are not won by psyops. Ask Nazi Germany. Still, it’s been a howler to watch NATOstan media on Kharkov, gloating in unison about “the hammer blow that knocks out Putin”, “the Russians are in trouble”, and...

WAR - Regional conflict brewing in the Mediterranean

OSINTdefender @sentdefender 2h There are Unconfirmed reports that Turkish Armored Units are being transported from the Turkish Mainland by Ferry to the Demilitarized Greek-Claimed Island of Imbros, this comes less than 24 hours since President Erdogan said a Turkish Attack on Greece could not...

WAR - Greek forces fire on a ship in Aegean Sea amid rising danger of war with Turkey

Greek forces fire on a ship in Aegean Sea amid rising danger of war with Turkey On Saturday, the Greek coast guard opened fire on the Comoros-flagged ship Anatolian, as it sailed in international waters 11 nautical miles off the Turkish island of Bozcaada at the Aegean Sea entrance of the...

WAR - Main Armenia Versus Azerbaijan War Thread - Open Hostilities Underway Now

MoD of Armenia @ArmeniaMODTeam (1/2) The statement ofthe Armenian MoD The claims of the #Azerbaijan'i MoD that the shelling was started by the #Armenia'n side are completely #false. Moreover, the military-political leadership of was preparing an obvious information base for this provocation...

WAR - CHINA THREATENS TO INVADE TAIWAN

Taiwan warns Russia, China ties 'harm' international peace - Insider Paper AFP Taiwan said on Friday ties between Russia and China were a threat to global peace and that the international community must resist the “expansion of...

ALERT - The Winds of War Blow in Korea and The Far East

https://twitter.com/Apex_WW Apex @Apex_WW Update: South Korea National Security Advisor: South Korea, U.S., Japan agree there will be no soft response in case of North Korea nuclear test "Should North Korea conduct its seventh nuclear test, our (SK, U.S., Japan) reaction will certainly be...

WAR - Main Persian Gulf Trouble thread

Israel Radar @IsraelRadar_com Iran's supreme leader Khamenei cancelled all public appearances due to illness, is currently under medical observation, @kann_new reports; full details about his health condition unknown at this time. 12:03 PM · Sep 16, 2022·Twitter Web App Iran’s Supreme...

=====================================================================

Hummm.........

Posted for fair use.....

Back Door Proliferation: The IAEA, AUKUS And Nuclear Submarine Technology – OpEd

In Vienna, China’s permanent mission to the United Nations has been rather exercised of late. Members of the mission have been particularly irate with the International Atomic Energy Agency and its…

www.eurasiareview.com

www.eurasiareview.com

Back Door Proliferation: The IAEA, AUKUS And Nuclear Submarine Technology – OpEd

September 18, 2022 Binoy Kampmark 0 CommentsBy Binoy Kampmark

In Vienna, China’s permanent mission to the United Nations has been rather exercised of late. Members of the mission have been particularly irate with the International Atomic Energy Agency and its Director General, Rafael Grossi, who addressed the IAEA’s Board of Governors on September 12.

Grossi was building on a confidential report by the IAEA which had been circulated the previous week concerning the role of nuclear propulsion technology for submarines to be supplied to Australia under the AUKUS security pact.

When the AUKUS announcement was made in September last year, its significance shook security establishments in the Indo-Pacific. It was also no less remarkable, and troubling, for signalling the transfer of otherwise rationed nuclear technology to a third country. As was rightly observed at the time by Ian Stewart, executive director of the James Martin Center in Washington, such “cooperation may be used by non-nuclear states as more ammunition in support of a narrative that the weapons states lack good faith in their commitments to disarmament.”

Having made that sound point, Stewart, revealing his strategic bias, suggested that, as such cooperation would not involve nuclear weapons by Australia, and would be accompanied by safeguards, few had reason to worry. This was all merely “a relatively straightforward strategic step.”

James M. Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, was far less sanguine. “[T]he nonproliferation implications of the AUKUS submarine deal are both negative and serious.” Australia’s operation of nuclear-powered submarines would make it the first non-nuclear weapon state to manipulate a loophole in the inspection system of the IAEA.

In setting this “damaging precedent”, aspirational “proliferators could use naval reactor programs as cover for the development of nuclear weapons – with the reasonable expectation that, because of the Australia precedent, they would not face intolerable costs for doing so.” It did not matter, in this sense, what the AUKUS members intended; a terrible example that would undermine IAEA safeguards was being set.

A few countries in the region have been quietly riled by the march of this technology sharing triumvirate in the Indo-Pacific. In a leaked draft of its submission to the United Nations tenth review conference of the Parties to the Treaty of the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT RevCon), Indonesia opined that the transfer of nuclear technology for military purposes was at odds with the spirit and objective of the NPT.

In the sharp words of the draft, “Indonesia views any cooperation involving the transfer of nuclear materials and technology for military purposes from nuclear-weapon states to any non-nuclear weapon states as increasing the associated risks [of] catastrophic humanitarian and environmental consequences.”

At the nuclear non-proliferation review conference, Indonesian diplomats pushed the line that nuclear material in submarines should be monitored with greater stringency. The foreign ministry argued that it had achieved some success in proposing for more transparency and tighter scrutiny on the distribution of such technology, claiming to have received support from AUKUS members and China. “After two weeks of discussion in New York, in the end all parties agreed to look at the proposal as the middle path,” announced Tri Tharyat, director-general for multilateral cooperation in Indonesia’s foreign ministry.

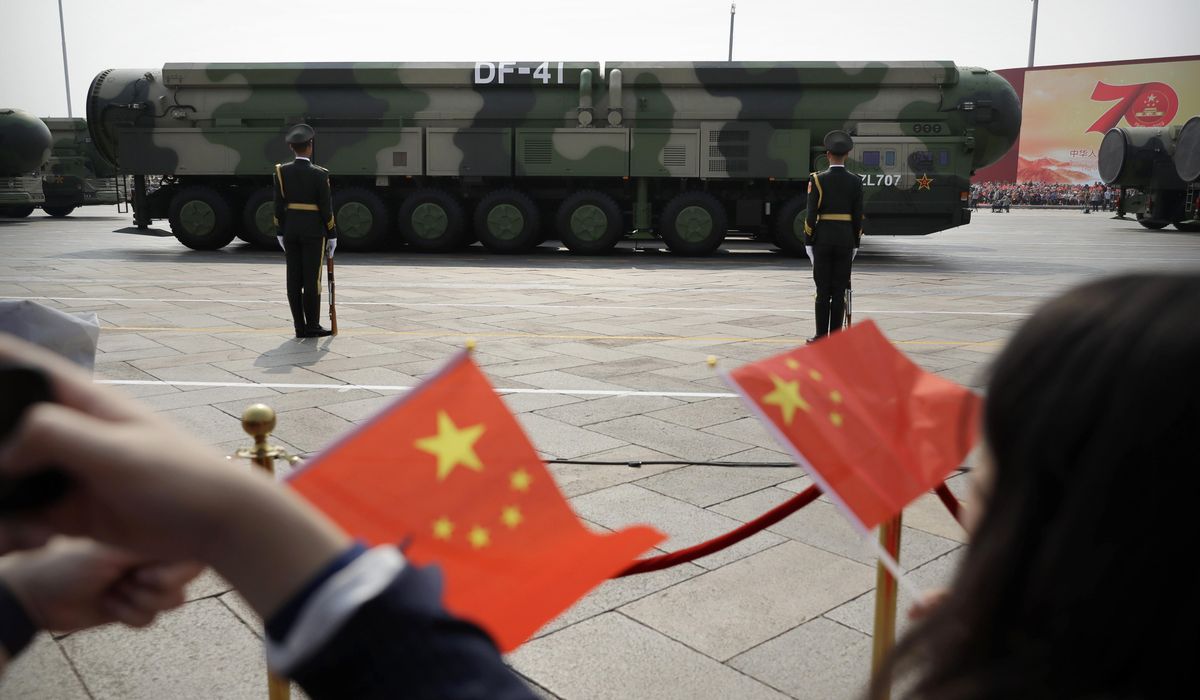

While serving to upend the apple cart of security in the region, AUKUS, in Jakarta’s view, also served to foster a potential, destabilising arms race, placing countries in a position to keep pace with an ever increasingly expensive pursuit of armaments. (Things were not pretty to start with even before AUKUS was announced, with China and the United States already eyeing each other’s military build-up in Asia.)

The concern over an increasingly voracious pursuit of arms is a view that Beijing has encouraged, with Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian having remarked that, “the US, the UK and Australia’s cooperation in nuclear submarines severely damages regional peace and stability [and] intensifies the arms race.”

Wang Qun, China’s Permanent Representative, told Grossi on September 13 that he should avoid drawing “chestnuts from the fire” in endorsing the nuclear proliferation exercise of Australia, the United States and the UK. Rossi, for his part, told the IAEA Board of Governors that four “technical meetings” had been held with the AUKUS parties, which had pleased the organisation. “I welcome the AUKUS parties’ engagement with the Agency to date and expect this to continue in order that they deliver their shared commitment to ensuring the highest non-proliferation and safeguard standards are met.”

The IAEA report also gave a nod to Canberra’s claim that proliferation risks posed by the AUKUS deal were minimal given that it would only receive “complete, welded” nuclear power units, making the removal of nuclear material “extremely difficult.” In any case, such material used in the units, were it to be used for nuclear weapons, needed to be chemically processed using facilities Australia did not have nor would seek.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning was less than impressed. “This report lopsidedly cited the account given by the US, the UK and Australia to explain away what they have done, but made no mention of the international community’s major concerns over the risk of nuclear proliferation that may arise from the AUKUS nuclear submarine cooperation.” It turned “a blind eye to many countries’ solemn position that the AUKUS cooperation violates the purpose and object of the NPT.”

Beijing’s concerns are hard to dismiss as those of a paranoid, addled mind. Despite China’s own unhelpful military build-up, attempts by the AUKUS partners to dismiss the transfer of nuclear technology to Australia as technically benign and compliant with the NPT is dangerous nonsense. Despite strides towards some middle way advocated by Jakarta, the precedent for nuclear proliferation via the backdoor is being set.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/GHAEXEXPTFE6XLIDQZMRNU4Q2U.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/T56QBU72ENGJFDW43F4OFETNJQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/SQ6IP2LJCNCSDINZW5RRN7VFEE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/DNIDNQPO2BDZ5PUOZ77HPQTEUI.jpg)