After the retreat: what now for Afghanistan?

After the retreat: what now for Afghanistan?

Emma Graham-Harrison

14-18 minutes

The public flogging in Obe district, captured on video that quickly went viral this spring, was a mistake, a local

Taliban judge admitted. Commanders were angry.

As the footage spread between urban Afghans, who shared it on their smartphones, it revived memories of darker times when the militants ruled the country, and an outpouring of revulsion.

Men with lashes take turns to bear down on a woman visibly bracing, even under her burqa, against the blows, and by the end screaming out in pain: “O God, I repent.” An audience of men and boys watch, or snap photos and videos.

The problem, the cleric explained, was not the punishment but the video, which circulated in April as the militants were consolidating control of the area. “She committed adultery, and I would have ordered the same thing,” he told the

Observer in a telephone interview. “But the commanders said that we shouldn’t have done it in public.”

Map of Afghanistan.

Years into taking up the post in the Taliban’s shadow administration it is a sentence he still hands down regularly for “adultery”, which in

Afghanistan can cover any sexual relationship outside marriage, and can sometimes even include rape. Men are flogged and then jailed, he added. “I recently ordered the flogging of a woman inside her home. Relatives and neighbours came to us and said there were witnesses to this man and woman being together. We lashed her 20 times.”

Obe sits just to the east of the silk-road city of Herat, a valley of grape and peach orchards nestled between two mountains, famous for the curative waters of a natural hot spring. In more peaceful times people used to head to the city at weekends for picnics, to escape the heat and dust of the city.

But for years the Taliban have been fighting in Obe’s fields and villages, and last month it became one of dozens of districts across Afghanistan to fall fully under the militants’ control, as foreign forces

accelerated a departure they are expected to complete this month. The experiences of people there offer a glimpse of what a country, or large swaths of one, ruled by the Taliban might look like, and it is a disturbing vision.

And the details of how Obe finally fell offer a worrying insight into the militants’ growing confidence, resources and ambition, and also the problems hobbling Afghan security forces – from lack of air support to questionable strategic decisions – as they start a new era of going into battle without foreign backup.

On Friday,

US troops left Bagram, the sprawling airbase north of Kabul that was the symbolic and operational heart of the American operation in Afghanistan. Fewer than 1,000 US troops are thought to be still in the country, mostly for security purposes in and around Kabul.

Britain

is expected to bring the last of its regular troops home from Afghanistan over the weekend to match the US departure, and in a few days Boris Johnson is expected to make a statement to parliament marking the change and outlining the UK’s future diplomatic presence in, and military posture towards, Afghanistan.

Afghan women fear the return of the Taliban. Photograph: Reuters/Alamy

America and its allies arrived in the country in 2001, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, to topple the Taliban and find terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden.

The al-Qaida leader is long dead, but few politicians are willing to dwell on the reality that the international forces are leaving with the Taliban – who seemed utterly routed 20 years ago –

resurgent on the ground.

Through withdrawal talks with the Americans, the militants have also gained a form of international recognition they had long craved. The group’s senior envoys have responded by burnishing the image they present to the wider world.

At peace talks in the Qatari capital Doha, and across other platforms including a

New York Times opinion column

by their deputy leader, the Taliban’s representatives have been presenting an image of change. They use the language of peace and reconciliation, and have promised women their rights as “granted by Islam – from the right to education to the right to work”.

Yet in Obe they have revived most of the brutal and misogynist policies that marked their rule in the 1990s, according to multiple accounts collected by the

Observer.

We spoke to civilians living in Obe, others who had recently fled, the Taliban judge, engineers working on district development projects, government soldiers who fought in the bitter last stand for the district’s centre, an activist who is in regular contact with women there, and local and provincial officials. Almost all asked to remain anonymous, for fear of reprisals against them or their relatives.

“The international platform for the Taliban is truly disturbing. We live under the Taliban, we deal with them and we know they have not changed,” said Halima Salimi, a women’s rights activist based in Herat who receives regular death threats for her work.

She is still in contact with fellow activists in Obe, who say they are now confined to their homes and barred from work.

On 14 June, the last government forces in the district were helicoptered out of a besieged outpost. The militants are confident enough of their control that last week they called a meeting at the mosque in the main street to lay out their laws and plans for Obe, which include a flat 10% tax on all earnings.

The district schools have been closed for years by fighting, or boycotted by parents worried their children will be caught in crossfire. But when they reopen, girls will not be allowed to study past sixth grade, interviewees said.

Women must wear the all-enveloping burqa and cannot work or leave their home for any reason without a male “guardian”, a role that can be filled even by prepubescent sons, nephews or brothers. Shopkeepers have been ordered not to serve women out alone, and Taliban beat any unaccompanied women they catch.

01:55

Joe Biden: 'It's time for American troops to come home from Afghanistan' – video

For women without a suitable relative, the militants have a complex system, said one mother of three who fled Obe after her home was destroyed in recent fighting.

“She must let the Taliban know there is no man in the house, and they will tell her she can only go to certain places – like here, here and here – making a kind of map restricting her movement.”

Mobile phones are regularly checked by Taliban fighters, another Obe resident said, and if they find music, dancing or anything supporting the government, the owner will be beaten. If they find pictures of him or her in government uniform, they are executed.

Physical punishment including amputations and floggings are handed down as sentences by judges, including the one who spoke to the Observer, who asked not to be named because he was not authorised to speak to journalists.

“Muslims agree with this. If you don’t give sharia punishment, crimes will rise. People come to us and say they are grateful,” said the judge. “When the government was in power, no robbery was investigated. Now after we came to power, people can leave their doors open.”

In his court, which meets regularly and hears three or four cases a day, often on land and water disputes, “testimony from two women equals that from one man”, he added.

The refugee mother conceded that the group had brought an end to lawlessness, but for her it was not enough to offset all the cruelty and restrictions.

“The Taliban have already made a really big reduction in robbery – I know many people support them and are satisfied because of this, but I don’t want them [ruling the area].

“They had special people responsible for beating women, they used rope or pieces of wood to hit them,” she said. Men are beaten for not praying, and not fasting during Ramadan, and there are other petty restrictions like a ban on makeup. “It was exactly like last time they were in power [before 2001]. I was in Obe then too.”

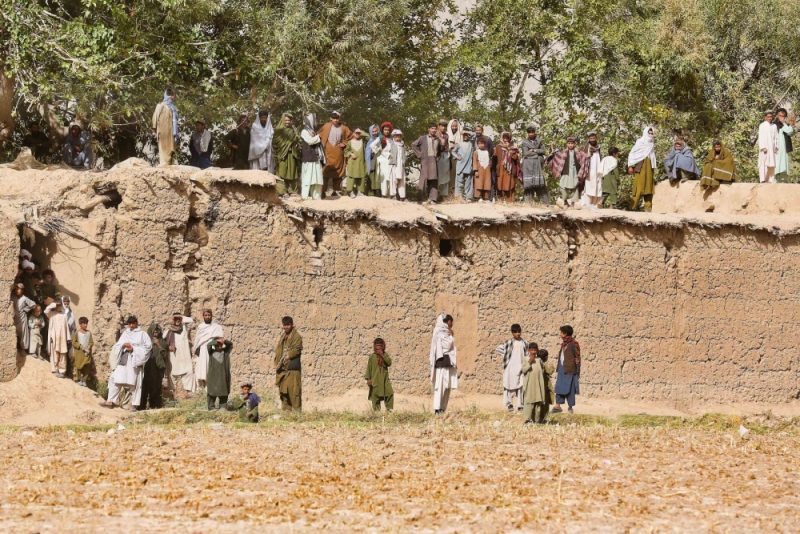

Afghan militia fighters with regular soldiers at a gathering in Kabul last month. Photograph: Rahmat Gul/AP

One man still living in the area said: “Of course you just worry about the children’s future.” There was a bleak sense of history repeating itself, he said. “I was only educated until fifth grade, then I had to drop out for the same reason.”

The Taliban, despite their public commitment to ending “the killing and maiming”, are accused of war crimes. In the cities they have been linked to

targeted assassinations; in Obe, locals say they have used families as human shields.

During the battle for the district centre, women and children were ordered not to leave at least one house the Taliban were using as a base for operations for several days, residents say. They believe the family were made to serve as insurance against airstrikes by government forces or American drones.

The comprehensive capture of the district centre, after years of the Taliban attacking and falling back, appears to have been made possible by an influx of fighters from other provinces, under a new commander. Rafi Shindandi, probably a nom de guerre, arrived in the area after Eid, which ended the fasting month of Ramadan in May. He brought around 60 or 70 fighters, from places including nearby Farah and Badghis provinces.

When they arrived, local Taliban warned a group of government-funded engineers working in Obe on development projects, including bridges and water supply, to leave. The engineers had previously built up a relationship with the insurgents to ensure that their civilian work, such as water supply projects, could go ahead without attacks or accidental targeting in battles.

“Local Taliban and elders told us when they arrived and warned they were dangerous,” he said. “We trusted the local fighters, but in war you can’t tell good and bad apart easily, and we didn’t have a relationship with the new ones.”

Sightings of reinforcement fighters were reported in other districts that fell to Taliban control, and may have been part of a tactic of preemptive strikes against areas that had been strongholds of resistance 20 years earlier.

“That the Taliban would launch widespread attacks while, or immediately after, US forces left was to be expected, but the scale and speed of the Afghan National Security Forces’ collapse was not,” said Kate Clark of the Afghanistan Analysts Network in a recent analysis of the Taliban’s takeover in much of the country’s north.

The insurgents held around a quarter of the country’s nearly 400 district centres at the end of June, the thinktank calculated from news reports and its own investigations. Clark went on to describe “the plunging morale of members of the ANSF in the field and … a new-found confidence among Taliban fighters that military victory was coming their way”.

In some provinces, almost all the areas beyond city limits have fallen; government supporters fear the Taliban is positioning for a push on provincial capitals. Although it has overrun several such capitals briefly in the past, it has not yet been able to take and hold them. That track record is likely to be put to the test soon.

Other factors undermining government forces are corruption, desertion and ill-thought-out policy. The air support vital to holding the Taliban at bay has dwindled, with the Afghan air force badly overstretched and the US now operating from thousands of miles away.

An Afghan soldier stands guard at Bagram airbase on Friday, the day of the US’s departure. Photograph: Mohammad Ismail/Reuters

In December last year, the government disbanded a supportive unit of the militia-like Afghan Local Police in Obe, under what looks increasingly like an ill-conceived demobilisation programme. Several other districts that fell to Taliban control had recently lost ALP forces as well, Clark wrote.

In Obe, the Taliban attack on the district centre had hardened into a siege by June. A few dozen men from the intelligence, police and army were stranded on a military base with just a glass of water a day, and dwindling food. They called desperately for air support or evacuation, but the only visitors who arrived were Red Crescent officials who had come to collect bodies.

The men had been reduced to stripping leaves off the trees to eat before a group of parents launched a three-day protest in Herat, demanding support for the besieged group. Initially polite, by day three the terrified and furious parents were burning tyres in the street and threatening suicide attacks. The next day, helicopters were dispatched, but for many it was already too late. “Bodies were carried out of injured men who would have survived if they got help sooner,” said one of the commandos bitterly.

At least one of the men trapped inside, who himself comes from Obe, has been quietly sounding out friends in the area and in Herat about organising a militia to try to reclaim the district.

For years, western-backed efforts aimed to disarm the country’s irregular militias. But the Taliban’s advances and the accelerated departure of foreign troops have convinced Afghans whose homes are threatened, and the officials who have to protect them, that they need more people to pick up guns and fight.

Militias are forming around the country, many encouraged, financed or even called up by the government itself.

The fighter from Obe has lost brothers, his father and at least 20 more distant relatives to the Taliban, and refuses to consider surrender or collaboration. “The situation is catastrophic, and the government won’t even listen to me,” he said. “So now my work is just to be killed, or liberate my town.”

As the west departs, the Taliban are resurgent. They say they have changed – but misogyny and brutality still mark their rule

www.theguardian.com