jward

passin' thru

U.S.-Europe Communiqué on the Afghan Peace Process

Media Note

Office of the Spokesperson

May 7, 2021

The following is the text of a communiqué issued by the United States of America, European Union, France, Germany, Italy, NATO, Norway, and the United Kingdom on the Afghan Peace Process.

Begin Text:

Special Envoys and Special Representatives of the United States of America, European Union, France, Germany, Italy, NATO, Norway, and the United Kingdom met in Berlin on May 6th, 2021.

Respectful of the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Afghanistan, participants exchanged views on the current status of the Afghanistan peace process and discussed ways to support the Afghan people’s desire for a just and lasting peace. To that end, participants:

www.state.gov

www.state.gov

Media Note

Office of the Spokesperson

May 7, 2021

The following is the text of a communiqué issued by the United States of America, European Union, France, Germany, Italy, NATO, Norway, and the United Kingdom on the Afghan Peace Process.

Begin Text:

Special Envoys and Special Representatives of the United States of America, European Union, France, Germany, Italy, NATO, Norway, and the United Kingdom met in Berlin on May 6th, 2021.

Respectful of the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Afghanistan, participants exchanged views on the current status of the Afghanistan peace process and discussed ways to support the Afghan people’s desire for a just and lasting peace. To that end, participants:

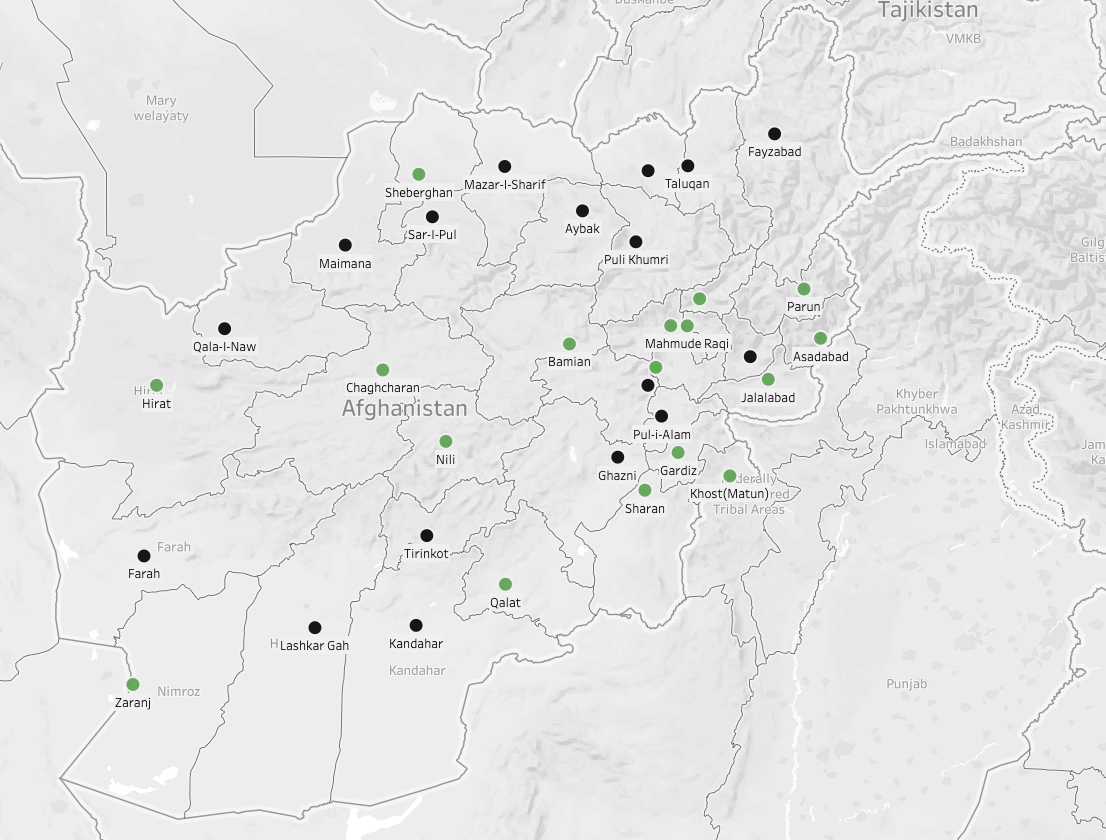

- Acknowledged the widespread and sincere demand of the Afghan people for an end to the war and a fair and lasting peace, and confirmed that such a peace can only be achieved through an inclusive, negotiated political settlement among Afghans. Participants affirmed their commitment to UNSC resolution 2513 (2020) and emphasized that they oppose the establishment in Afghanistan of any government by force which would constitute a threat to regional stability.

- Highlighted the need to accelerate the pace of the Afghan-led and Afghan-owned peace negotiations and committed to work with the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the Taliban, and other Afghan political and civil society leaders to reach a comprehensive and sustainable peace agreement and political compromise that ends the war for the benefit of all Afghans and that contributes to regional stability and global security.

- Expressed appreciation to the Government of Qatar for its long-standing contribution to facilitate the peace process, including hosting and supporting Afghanistan Peace Negotiations since September 12th, 2020, and underlined their support for the continuation of discussions between the parties’ negotiating teams in Doha. Appreciated the offer from the Republic of Turkey, the United Nations, and the State of Qatar to co-convene a senior-level peace conference in Istanbul and welcomed plans for related events to channel civil society voices into the process. Urged the immediate resumption, without pre-conditions, of substantive negotiations on the future of Afghanistan with the aim to develop and negotiate realistic compromise positions on power sharing that can lead to an inclusive and legitimate government and a just and durable settlement.

- Welcomed an expanded role for the United Nations in contributing to the Afghanistan peace and reconciliation process, including by leveraging its considerable experience and expertise in supporting other peace processes.

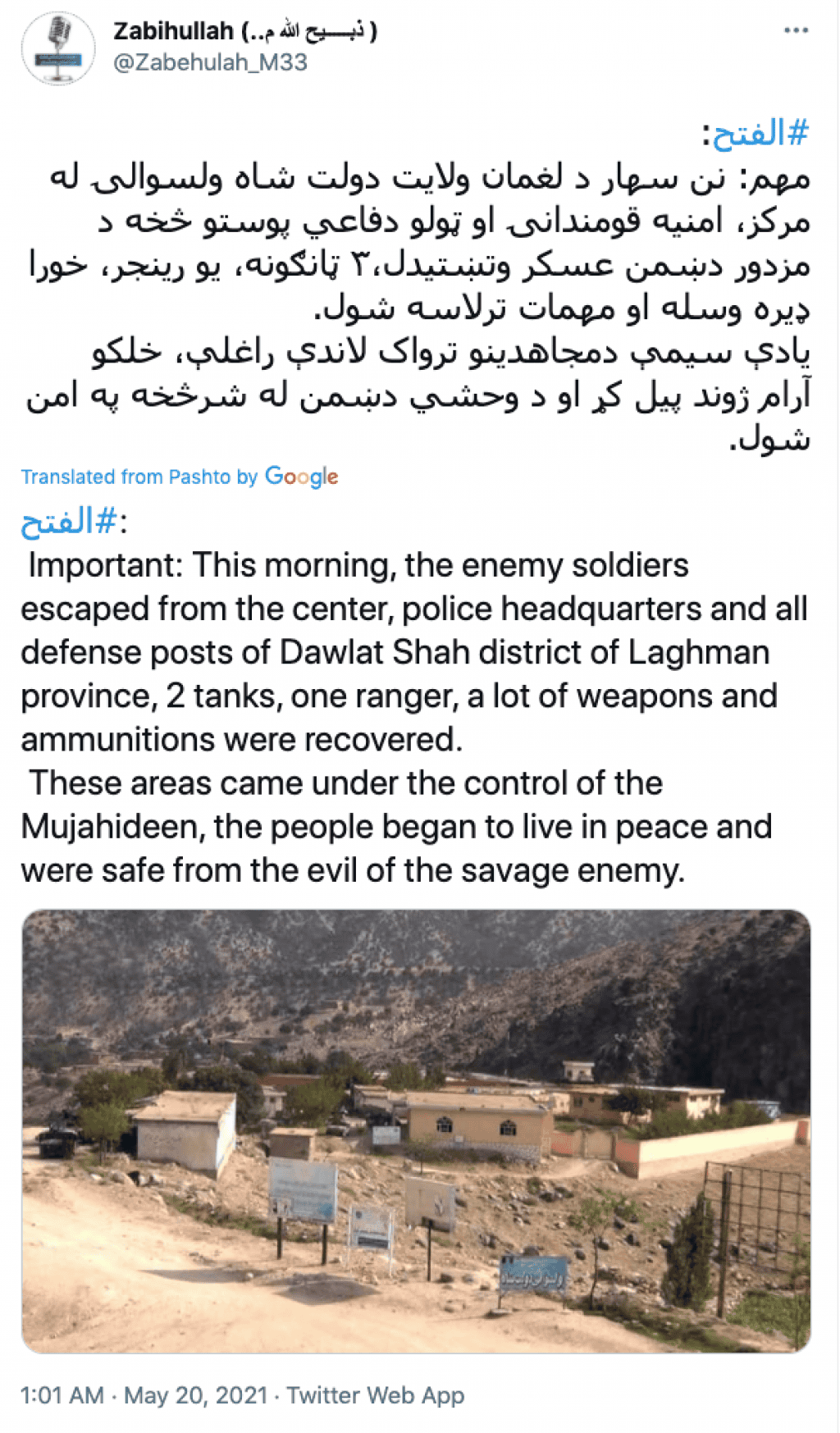

- Strongly condemned the continued violence in Afghanistan for which the Taliban are largely responsible and demanded all parties to take immediate and necessary steps to reduce violence and in particular, to avoid civilian casualties in order to create an environment conducive to reaching a political settlement. Participants further called on all parties to respect their obligations under international humanitarian law in all circumstances, including those related to protection of civilians, and urged all sides to immediately agree on steps that enable the successful implementation of a permanent and comprehensive ceasefire.

- In this regard, participants called upon the Taliban to stop their undeclared spring offensive, to refrain from attacks against civilians, and to stop immediately all attacks in the vicinity of hospitals, schools, universities, mosques and other civilian areas. In particular, participants demanded an immediate end to the campaign of targeted assassinations against civil society leaders, the clergy, journalists and other media workers, human rights defenders, healthcare personnel, judicial employees and other civilians.

- Following the April 14 announcement by the United States and NATO that U.S. and Resolute Support Mission forces will conduct an orderly, coordinated, and deliberate withdrawal from Afghanistan, to be concluded by September 11, 2021 participants reiterated that during the withdrawal, the safety of international troops must be ensured and that any Taliban attacks on our troops during this period will be met with a forceful response. Participants stressed that the process of the troop withdrawal must not serve as an excuse for the Taliban to suspend the peace process and that good-faith political negotiations must proceed in earnest.

- In light of this withdrawal of forces, the participants recommitted to a strong and enduring partnership with Afghanistan, its governing and security institutions and its people. Participants also agreed that substantial international development assistance will be needed for Afghanistan’s stability during peace negotiations and reaffirmed their commitment to mobilize international support for reconstruction following a peace agreement, based on the conditions as laid out in the outcome documents of the 2020 Geneva Conference, including the preservation and respect for the rights of all Afghans, including women and minorities. Participants underscored their commitment to conditional civilian assistance to Afghanistan beyond a military withdrawal with the aim of ensuring a better future for the Afghan people.

- Reaffirmed that any peace agreement must protect the rights of all Afghans, including women, youth, and minorities, and must respond to the strong desire of Afghans to sustain and build on the economic, social, political, and development gains achieved since 2001, including greater adherence to the rule of law, respect for Afghanistan’s international obligations, and improvements in inclusive and accountable governance. Highlighted that the Afghan parties’ ownership and leadership of intra-Afghan negotiations is important for a successful outcome. Reiterated that a stable, safe and prosperous Afghanistan is dependent on women playing full and meaningful roles in the peace negotiations and all parts of society, including in government.

- Underscored that the Taliban and the Government of the Islamic Republic must fulfill their counterterrorism commitments including to prevent al-Qaida, Daesh, or other terrorist groups and individuals from using Afghan soil to threaten or violate the security of any other country; not to host members of these groups; and to prevent them from recruiting, training, or fundraising.

- Reiterated that diplomatic personnel and property are inviolable, and that the perpetrators of any attack or threat on foreign diplomatic personnel and properties in Afghanistan must be held accountable.

- Underscored that – while fully respecting the right of the Afghan people to self-determination – the countries and organizations represented at this meeting strongly advocate a durable and just political resolution that will result in the formation of a sovereign, unified, peaceful and democratic Afghanistan, free of terrorism and an illicit drug industry, which contributes to regional stability and global security.

- Reaffirmed that current and future support to any Afghan government relies on the adherence to the principles set out in the Afghanistan Partnership Framework and progress towards the outcomes in the Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework II as decided upon at the November 2020 Geneva donor’s conference.

- Participants called upon the Government of the Islamic Republic to effectively fight corruption and promote good governance, and to implement anti-corruption legislation. Participants stressed their conviction that widespread corruption undermines the foundations of the Republic as well as the ability of the international community to continue to support Afghan institutions.

- Urged the Taliban to facilitate access for delivery of humanitarian aid, without preconditions and in accordance with international humanitarian law, to the parts of the country under their effective control.

- Stressed the importance of fighting illegal drug production and trafficking and urged both sides to eliminate the drug threat in and from Afghanistan.

- Agreed that continued international support to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces will be necessary to ensure Afghanistan can defend itself against internal and external threats.

- Encouraged all concerned countries, in particular Afghanistan’s neighbors and countries of the region, to continue to support the Afghan people and constructively contribute to a lasting peace settlement and sustainable economic development in the interest of all.

- Thanked the negotiating team of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the negotiating team of the Taliban for their important contributions to today’s meeting via video and for the frank and open discussion on challenging issues.

- Expressed their appreciation to the German government for organizing these consultations and agreed to set the date and venue of the next meeting through diplomatic channels.

U.S.-Europe Communiqué on the Afghan Peace Process - United States Department of State

Respectful of the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Afghanistan, participants exchanged views on the current status of the Afghanistan peace process and discussed ways to support the Afghan people’s desire for a just and lasting peace.

www.state.gov

www.state.gov

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/Q4ZKYW6KY5KQZH7B3OMODMBT5E.jpg)