WAR - 09-12-2020-to-09-18-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(434) 08-22-2020-to-08-28-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** WAR - 08-22-2020-to-08-28-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** (435) 08-29-2020-to-09-04-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****...

www.timebomb2000.com

(438) 09-19-2020-to-09-25-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

WAR - 09-19-2020-to-09-25-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

Sorry for the delay folks.....Meat world will have it's pound of flesh...... WAR - 08-29-2020-to-09-04-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** Sorry for the delay....HC (432) 08-08-2020-to-08-14-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****...

www.timebomb2000.com

www.timebomb2000.com

(439) 09-26-2020-to-10-02-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

www.timebomb2000.com

www.timebomb2000.com

---------------------------------------------------

jward

passin' thru

56 minutes ago

‘Blue Homeland’ and the Irredentist Future of Turkish Foreign Policy - War on the Rocks

---------------------------------------------------

Hummm........

Posted for fair use.....

mwi.usma.edu

mwi.usma.edu

A Great Power War Could Require More Troops, and more Quickly, than the United States Can Generate—even with a Draft

Justin Lynch | October 1, 2020

Great power competition has become a popular topic in defense circles—and that’s putting it mildly. The National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy both address it, events are held to discuss it, and the phrase may even be so popular that it becomes a cliche. Despite this focus, very little literature about the topic addresses a closely related and pressing issue (especially given the prospect of competition between great powers becoming conflict between great powers): the United States’ ability to quickly generate trained personnel to replace field losses during high-intensity conflicts. As long as this remains unaddressed, the United States will struggle to understand the limitations of its conventional military power in protracted wars.

If the United States needed to, it could almost certainly put one million new soldiers under arms. The issue here is not the ability to draft a large number of people; it’s the draft’s inability to train and deploy soldiers quickly enough to preserve strategic and operational advantages in a peer conflict. The best way to understand this issue is through a thought experiment. What follows is not a predictive model. It is a tool to help explain the implications of the military’s force structure and the Selective Service System’s policies. For simplicity’s sake, it will only address Army personnel.

Thought Experiment: Is the Selective Service System Ready for Great Power Conflict?

Background

The most likely scenario for a draft is a great power war. Many pundits today argue that nuclear weapons, economic entanglement, and other factors mean that any great power war will be short. However, earlier this year, the Center for a New American Security published “Protracted Great-Power War: A Preliminary Assessment.” In it, Dr. Andrew Krepinevich argues that there are contingencies in which nuclear-armed combatants will impose constraints on vertical escalation even while remaining committed enough to continue fighting a high-intensity conflict for an extended period.

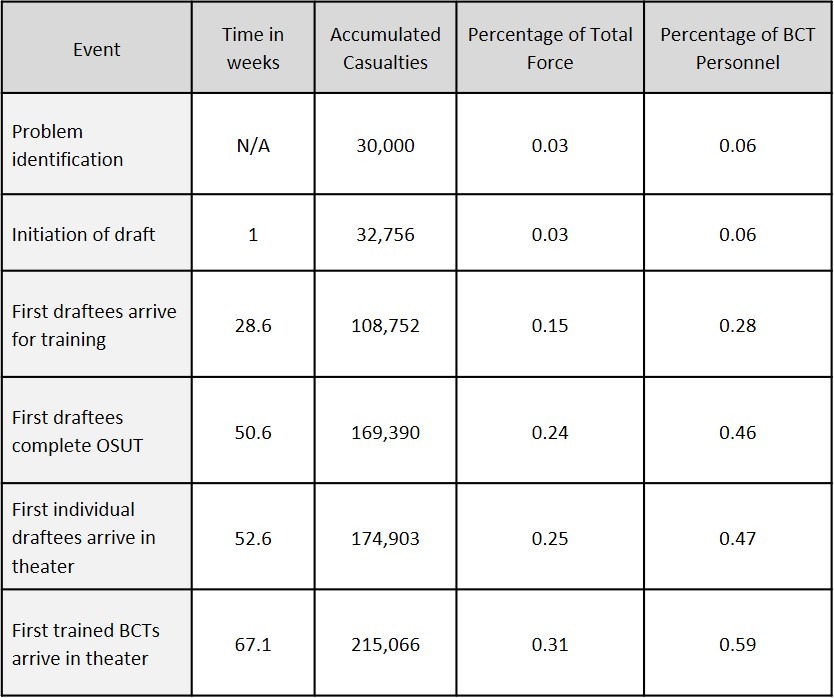

The United States fought two great power wars against peer adversaries in the twentieth century, World War I and World War II. Adversaries in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan did not have the same relative economic, technological, or military capabilities, and therefore do not meet the criteria for great power conflict. During World War I, 106,378 American soldiers died and 193,663 suffered non-fatal wounds over the fifty-four weeks between the start and finish of US combat operations. During World War II, 318,274 American soldiers died and 565,861 suffered non-fatal wounds during 191 weeks between the beginning and end of combat operations. If it is assumed based on trends from World War II that only 20 percent of treated, wounds were able to return to duty, the United States averaged a loss of 4,213 soldiers per week during protracted great power wars against peer rivals.

Congress authorizes the Army an end strength of 478,000 Regular Army, 189,250 Army Reserve, and 335,500 Army National Guard soldiers. This force has thirty-one active duty and National Guard brigade combat teams (BCTs) composed of 480,000 soldiers. The rest of the Army’s manpower is assigned to the institutional Army, such as schools, as well as functional and multifunctional brigades.

Scenario

Consider a scenario in which the United States is fighting a major, non-nuclear, protracted war against a great power adversary. As noted above, Dr. Krepinevich argues this to be both politically and strategically feasible. Assume the United States will lose thirty thousand soldiers before military and political leaders decide the Army will not be able to continue to meet its operational requirements with its existing force structure. Once the government has that realization, it could turn to the Selective Service System.

Timeline

To initiate a draft, Congress needs to amend the Military Selective Service Act. It is unlikely that doing so would be popular among the American people. Richard Kohn, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who studies war and the military, has described any move to reinstate the draft as likely to be “one of the most unpopular proposals presented to the Congress in many years.” Assume it would take one week for a hypothetical Congress to authorize and a hypothetical president to initiate a draft. Once this takes place, the Selective Service System is required to deliver the first inductees to the military for training within 193 days of its activation, or 27.5 weeks.

The inductees’ next step would be basic training. Drafts have historically been used to create large numbers of infantry soldiers. Today, the US Army’s infantry training, or one-station unit training, lasts twenty-two weeks. It is reasonable to assume that it would take an additional two weeks for newly drafted soldiers to begin arriving in theater to fight. If the above timeline holds true, it would take 368 days—just over one year—from the time military and political leaders realize the US Army’s force structure is insufficient to meet a conflict’s demands for the first draftees to arrive in theater.

Continued......

(434) 08-22-2020-to-08-28-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** WAR - 08-22-2020-to-08-28-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** (435) 08-29-2020-to-09-04-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****...

www.timebomb2000.com

(438) 09-19-2020-to-09-25-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

WAR - 09-19-2020-to-09-25-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

Sorry for the delay folks.....Meat world will have it's pound of flesh...... WAR - 08-29-2020-to-09-04-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** Sorry for the delay....HC (432) 08-08-2020-to-08-14-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****...

(439) 09-26-2020-to-10-02-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

WAR - 09-26-2020-to-10-02-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(436) 09-05-2020-to-09-11-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** WAR - 09-05-2020-to-09-11-2020___****THE****WINDS****of****WAR**** (433)...

---------------------------------------------------

jward

passin' thru

56 minutes ago

‘Blue Homeland’ and the Irredentist Future of Turkish Foreign Policy - War on the Rocks

---------------------------------------------------

Hummm........

Posted for fair use.....

A Great Power War Could Require More Troops, and more Quickly, than the United States Can Generate—even with a Draft - Modern War Institute

Great power competition has become a popular topic in defense circles—and that’s putting it mildly. The National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy both address it, events are held to […]

mwi.usma.edu

mwi.usma.edu

A Great Power War Could Require More Troops, and more Quickly, than the United States Can Generate—even with a Draft

Justin Lynch | October 1, 2020

Great power competition has become a popular topic in defense circles—and that’s putting it mildly. The National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy both address it, events are held to discuss it, and the phrase may even be so popular that it becomes a cliche. Despite this focus, very little literature about the topic addresses a closely related and pressing issue (especially given the prospect of competition between great powers becoming conflict between great powers): the United States’ ability to quickly generate trained personnel to replace field losses during high-intensity conflicts. As long as this remains unaddressed, the United States will struggle to understand the limitations of its conventional military power in protracted wars.

If the United States needed to, it could almost certainly put one million new soldiers under arms. The issue here is not the ability to draft a large number of people; it’s the draft’s inability to train and deploy soldiers quickly enough to preserve strategic and operational advantages in a peer conflict. The best way to understand this issue is through a thought experiment. What follows is not a predictive model. It is a tool to help explain the implications of the military’s force structure and the Selective Service System’s policies. For simplicity’s sake, it will only address Army personnel.

Thought Experiment: Is the Selective Service System Ready for Great Power Conflict?

Background

The most likely scenario for a draft is a great power war. Many pundits today argue that nuclear weapons, economic entanglement, and other factors mean that any great power war will be short. However, earlier this year, the Center for a New American Security published “Protracted Great-Power War: A Preliminary Assessment.” In it, Dr. Andrew Krepinevich argues that there are contingencies in which nuclear-armed combatants will impose constraints on vertical escalation even while remaining committed enough to continue fighting a high-intensity conflict for an extended period.

The United States fought two great power wars against peer adversaries in the twentieth century, World War I and World War II. Adversaries in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan did not have the same relative economic, technological, or military capabilities, and therefore do not meet the criteria for great power conflict. During World War I, 106,378 American soldiers died and 193,663 suffered non-fatal wounds over the fifty-four weeks between the start and finish of US combat operations. During World War II, 318,274 American soldiers died and 565,861 suffered non-fatal wounds during 191 weeks between the beginning and end of combat operations. If it is assumed based on trends from World War II that only 20 percent of treated, wounds were able to return to duty, the United States averaged a loss of 4,213 soldiers per week during protracted great power wars against peer rivals.

Congress authorizes the Army an end strength of 478,000 Regular Army, 189,250 Army Reserve, and 335,500 Army National Guard soldiers. This force has thirty-one active duty and National Guard brigade combat teams (BCTs) composed of 480,000 soldiers. The rest of the Army’s manpower is assigned to the institutional Army, such as schools, as well as functional and multifunctional brigades.

Scenario

Consider a scenario in which the United States is fighting a major, non-nuclear, protracted war against a great power adversary. As noted above, Dr. Krepinevich argues this to be both politically and strategically feasible. Assume the United States will lose thirty thousand soldiers before military and political leaders decide the Army will not be able to continue to meet its operational requirements with its existing force structure. Once the government has that realization, it could turn to the Selective Service System.

Timeline

To initiate a draft, Congress needs to amend the Military Selective Service Act. It is unlikely that doing so would be popular among the American people. Richard Kohn, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who studies war and the military, has described any move to reinstate the draft as likely to be “one of the most unpopular proposals presented to the Congress in many years.” Assume it would take one week for a hypothetical Congress to authorize and a hypothetical president to initiate a draft. Once this takes place, the Selective Service System is required to deliver the first inductees to the military for training within 193 days of its activation, or 27.5 weeks.

The inductees’ next step would be basic training. Drafts have historically been used to create large numbers of infantry soldiers. Today, the US Army’s infantry training, or one-station unit training, lasts twenty-two weeks. It is reasonable to assume that it would take an additional two weeks for newly drafted soldiers to begin arriving in theater to fight. If the above timeline holds true, it would take 368 days—just over one year—from the time military and political leaders realize the US Army’s force structure is insufficient to meet a conflict’s demands for the first draftees to arrive in theater.

Continued......

It's the new Concorde! Jet start-up company Boom unveils...

It's the new Concorde! Jet start-up company Boom unveils... Astronauts aboard the International Space Station receive...

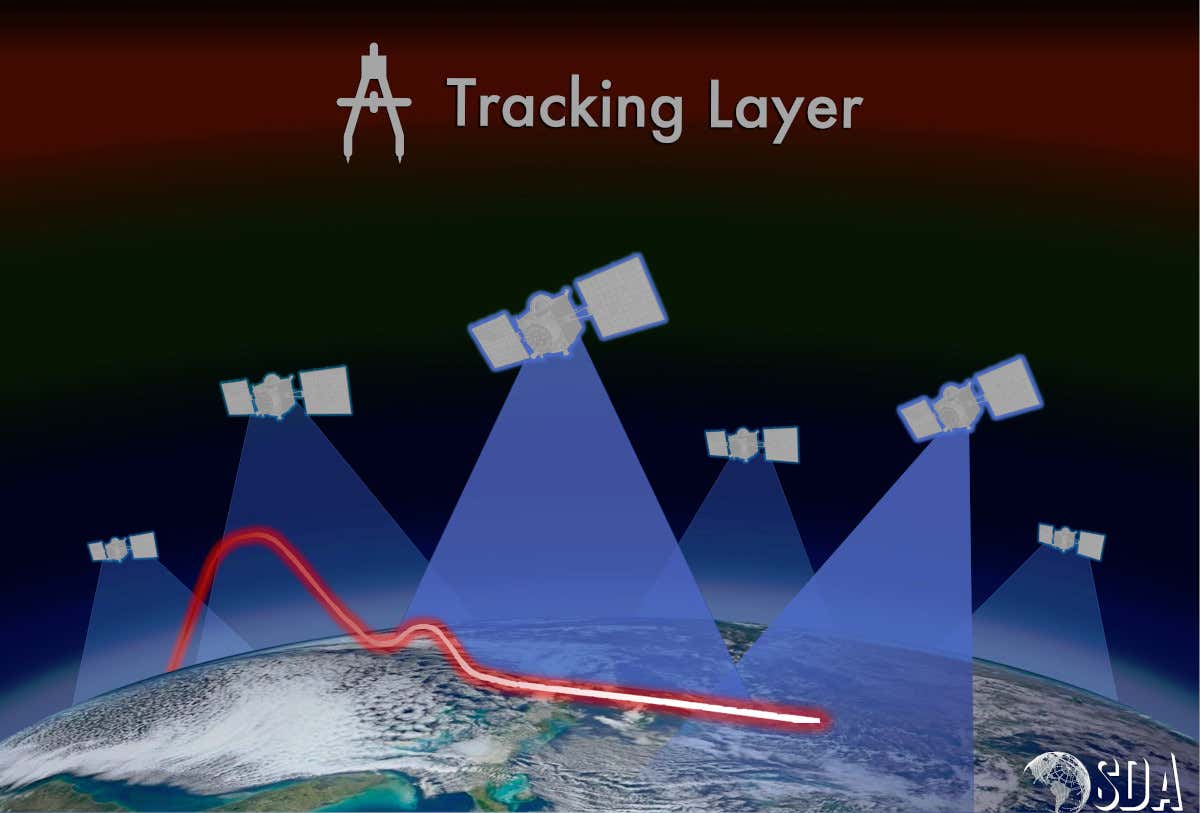

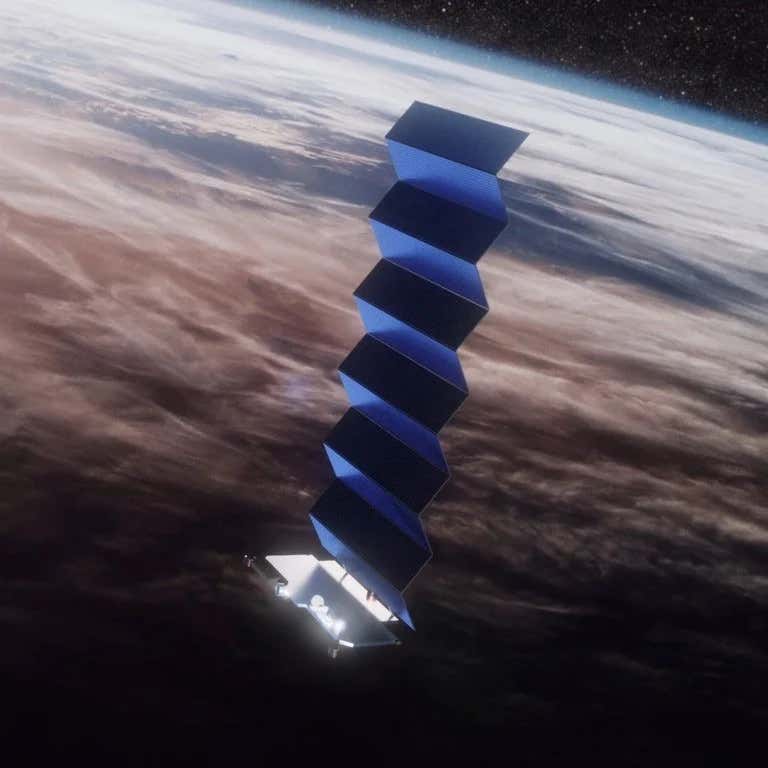

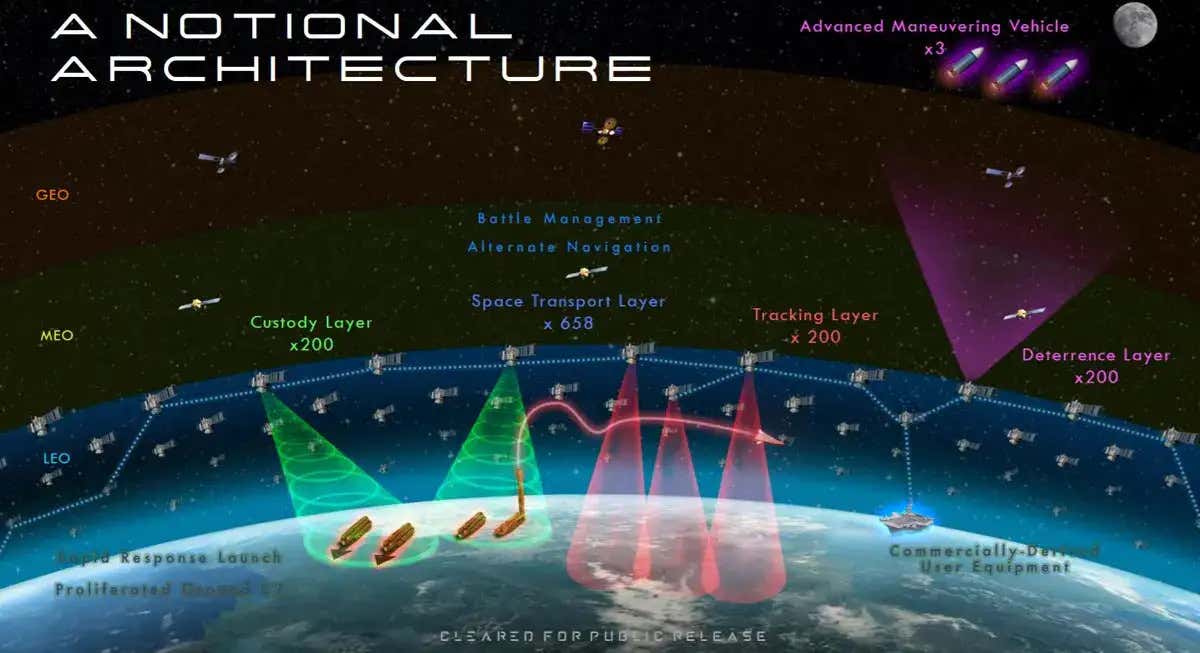

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station receive... Elon Musk's SpaceX wins $149 million contract to build..

Elon Musk's SpaceX wins $149 million contract to build.. Elon Musk's SpaceX provides Washington towns ravaged by...

Elon Musk's SpaceX provides Washington towns ravaged by...

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/I5VPMTWSHVD2ZFXOSZIVNNQNYM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/TZDVNNX6KBAVLOOSN7ARVZONE4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/R5N7KPVZKVDADHK5SSJOHIVIUE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/4P6AFFVKC5D3XEL6AUL56RI44U.jpg)