Washington Is Avoiding the Tough Questions on Taiwan and China

The Case for Reconsidering U.S. Commitments in East Asia

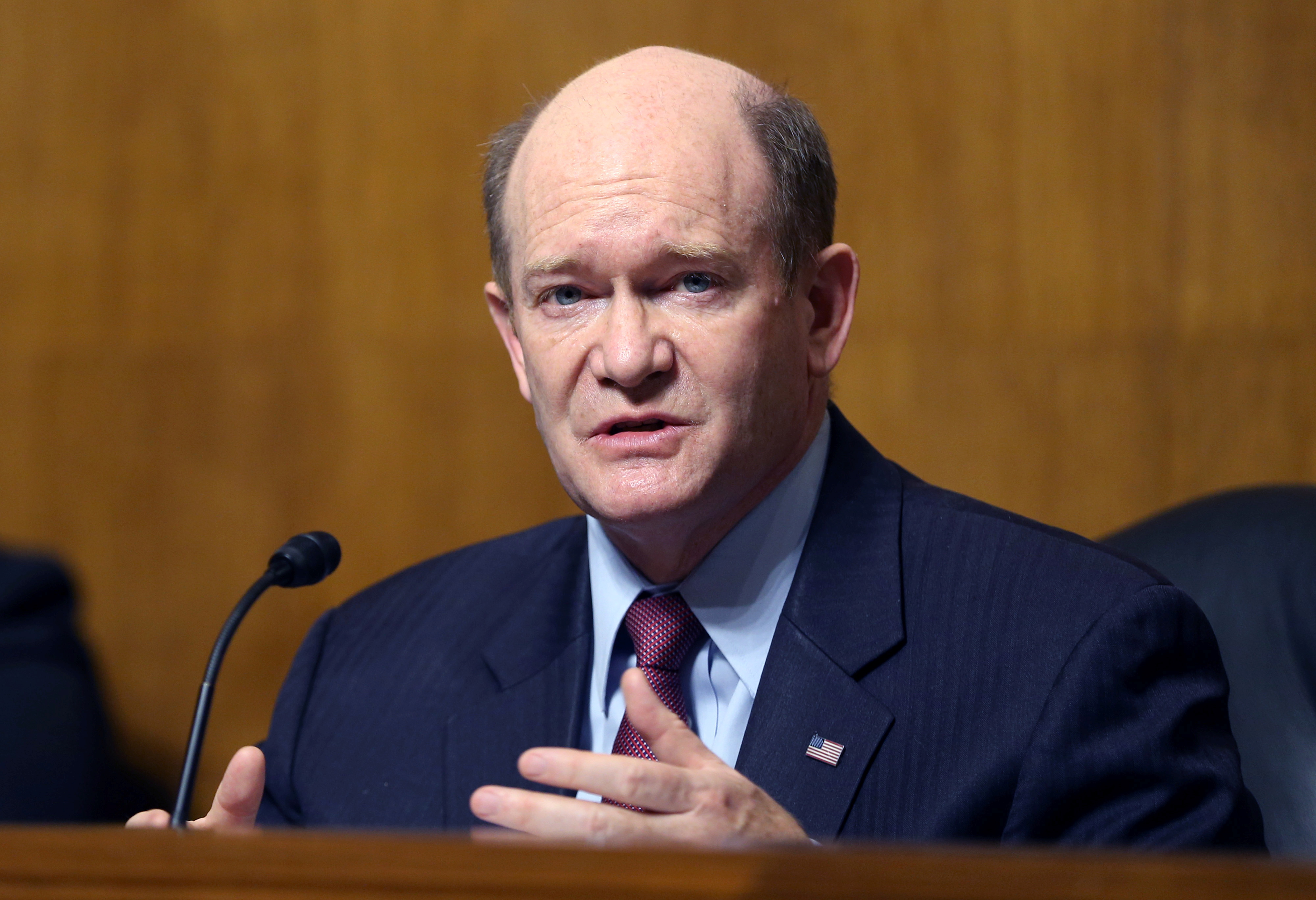

By Charles L. Glaser

April 28, 2021

The USS Ronald Reagan near Busan, South Korea, October 2017

MacAdam Kane Weissman / Reuters

On China, U.S. policymakers have reached a near consensus: the country is a greater threat than it seemed a decade ago, and so it must now be met with increasingly competitive policies. What little debate does exist focuses on questions about how to enhance U.S. credibility, what role U.S. allies should play in balancing against China, and whether it is possible to blunt Beijing’s economic coercion. But the most consequential question has been largely overlooked: Should the United States trim its East Asian commitments to reduce the odds of going to war with China?

The question of which commitments to keep and which to cut should come up whenever there are big shifts in the global balance of power. A rising power may be able to achieve previously unobtainable goals and embrace new goals, while the declining power may find that its existing commitments are becoming costlier and riskier to maintain.

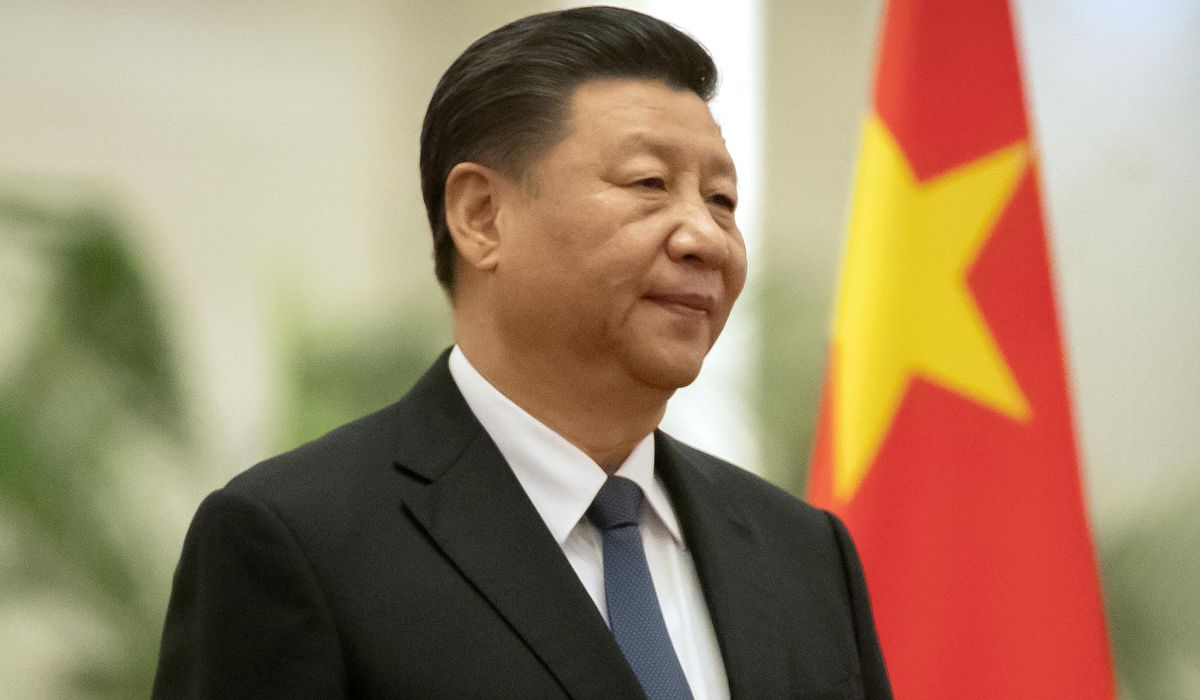

Such is the case with China and the United States today. Beijing has acquired military capabilities that were far beyond its reach a couple of decades ago. It has built up its “anti-access/area-denial” (A2/AD) capabilities, which are designed to prevent U.S. forces from operating close to Chinese territory. It now has a reasonable prospect of prevailing in a war over Taiwan and is acquiring the ability to sustain naval forces across the South China Sea. At the same time, its leaders are becoming more provocative and have made it exceedingly clear that unification with Taiwan is a pressing goal. China’s improved military capabilities reduce the United States’ ability to deter, and its increasingly intense maritime disputes raise the risk of accidents. As a result, a terrifying prospect is growing more likely: a major war between the world’s two foremost powers.

The emerging debate over U.S. China policy, however, recognizes only half of the logic of decline. Officials and analysts understand that as its capabilities increase, China will increasingly challenge U.S. commitments, and the probability of war will rise. But they are forgetting the second part of the equation: that for the declining power, the best option may be to cut back on its commitments. In East Asia, that would mean giving Beijing greater leeway in the South China Sea, letting go of Taiwan, and accepting that the United States is no longer the dominant power it once was in the region. These are hard choices, but maintaining the status quo is also a choice—and an increasingly dangerous one.

COMMITMENT ISSUES

To evaluate the United States’ commitments in East Asia, one must first rank the country’s interests there and estimate China’s capability to threaten them. All else being equal, Washington should be much more reluctant to reduce commitments that protect vital interests than ones that protect secondary interests. Fortunately, the one truly vital interest—the safety of the U.S. homeland—is not at risk. The United States and China are separated by a vast ocean, which makes conventional invasion virtually impossible. And even though China is modernizing its nuclear force, the U.S. arsenal is far bigger and more advanced. Washington will be able to maintain its deterrent capabilities with ease.

Next in this hierarchy of U.S. interests is the protection of East Asian allies—chief among them Japan and South Korea. For decades, the United States has cherished its security alliances with these large, rich, and strategically located countries. U.S. leaders still consider these relationships essential for preventing China from dominating its region, stopping South Korea and Japan from obtaining nuclear weapons, and preserving U.S. global leadership. Even scholars who advocate a more limited grand strategy of “offshore balancing” and wish to withdraw U.S. forces from Europe and the Persian Gulf maintain that U.S. alliances in Asia are necessary.

The prospects for defending these interests remain good. China’s ability to threaten U.S. allies is growing, but Japan, with U.S. help, should be able to fend off a Chinese attack. Invasion across several hundred miles of water has never been easy, and it is even harder today thanks to advanced surveillance technologies and accurate conventional weapons. Although China would have an easier time enacting a blockade designed to strangle and coerce Japan, that, too, would likely fail. Japan lies beyond the effective reach of

China’s A2/AD capabilities and could thus be supplied from its eastern ports. South Korea, closer to China, is

more vulnerable, but it, too, would likely prevail with U.S. help.

A terrifying prospect is growing more likely: a major war between the world’s two foremost powers.

Further down the hierarchy of U.S. interests is Taiwan. Since formally recognizing China in 1979, the United States has maintained unofficial relations with the Taiwanese government. Washington has signaled a somewhat ambiguous commitment to defend the island if China launches an unprovoked attack and has sold it tens of billions of dollars’ worth of arms. Compared with the U.S. commitment to Japan and South Korea, the obligation to Taiwan is much riskier. Beijing has both the motive and, increasingly, the means to forcibly bring Taiwan under its control. Chinese leaders consider the island part of China, and with only 110 miles separating Taiwan from the mainland, it is more vulnerable to Chinese conventional forces.

Taiwan is not a vital U.S. interest—its size and wealth put it at a rank below the major powers—but it is a vibrant democracy of 23 million people. Unlike Japan and South Korea, Taiwan is rarely framed in terms of U.S. security. Instead, the key rationales that U.S. officials offer for protecting the island are ideological and humanitarian: democracies in general should be defended, and Taiwan in particular is worthy of protection, since it is a precious success story that would no doubt be snuffed out were it to fall under China’s authoritarian control. Beginning in the 1980s, Beijing spoke of “one country, two systems,” the idea that Taiwan would be integrated with the mainland but governed under its own system. That notion was always a bit tenuous. China’s recent repression of Hong Kong has made it appear entirely unrealistic.

Although the ideological and humanitarian rationales for protecting Taiwan are sound, many analysts go further, arguing that basic U.S. security interests are at stake, too. If Washington were to terminate its commitment to Taiwan, they say, U.S. credibility across the region would suffer. China would question whether the United States would actually come to the defense of Japan or South Korea. Harboring the same doubts, U.S. allies might be tempted to bandwagon with Beijing. Some analysts make a second claim, contending that by controlling Taiwan, China could extend its military reach by basing both its attack submarines and its nuclear-armed submarines there. The ability of U.S. conventional forces to reach China would be reduced; China’s ability to respond to a nuclear attack, increased.

But there is good reason to doubt this doomsday scenario. Even if it ended its commitment to Taiwan, the United States could preserve its credibility with Japan and South Korea. These allies would no doubt understand that Taiwan was less important to the United States than they are and that the risks of protecting it were much higher. Letting go of Taiwan should suggest little, if anything, about the strength of Washington’s commitment to Tokyo and Seoul. What’s more, the United States could take action to reinforce these commitments—for example, stationing more troops in the Indo-Pacific and further integrating military planning and operations with allies.

For a declining power, the best option may be to cut back on its commitments.

As for the effect that China’s control of Taiwan would have on its ability to fight the United States, there is likewise little cause for concern. Even if Chinese nuclear-armed submarines enjoyed newfound access to the Pacific Ocean, whose vast expanse might increase their survivability, the United States’ retaliatory capability would not be diminished. Its nuclear deterrent would remain highly effective. The conventional military threat is harder to assess, but again, there is evidence to suggest that the threat posed by Chinese submarines might be bigger, but not by much. China’s land- and sea-based forces already pose a threat to U.S. forces within range of China. Moreover, the U.S. Navy could likely deploy its antisubmarine warfare assets—attack submarines, maritime patrol aircraft, and ocean surveillance ships—to greatly reduce the ability of Chinese submarines to leave Taiwan. All that said, even if Chinese conventional capabilities did grow as a result of control over Taiwan, it wouldn’t matter as much; because the United States would no longer be committed to protecting Taiwan, the odds of a major war with China would drop precipitously.

Below Taiwan in the hierarchy of U.S. interests in East Asia lies the South China Sea. In these waters, many analysts argue, Washington has an interest in preventing China from interrupting the flow of trade. The United States has long sworn to preserve freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, made ambiguous commitments to protect the Philippines’ maritime claims, and criticized China for building military bases in the Spratly Islands.

Again, the danger of ending this commitment is probably overstated. In peacetime, of course, all countries have an interest in keeping these sea-lanes open. But even in the midst of a war in which China managed to close off the South China Sea, shipping that usually entered that sea after passing through the Strait of Malacca could instead bypass the South China Sea, reaching Japan and South Korea via the archipelagic waters of Indonesia and the Philippines. China, by contrast, would be in a much tighter spot. Goods coming to and from its major ports have little choice but to pass through the South China Sea. And even if China somehow managed to solve this problem, much of Chinese trade would still need to travel across the Indian Ocean, which would remain dominated by the U.S. Navy.

the case for concessions

Not all interests are created equal, nor are the threats to them equivalent. So why should the United States treat its varied interests in East Asia the same way? The alliances with Japan and South Korea are both important and relatively low risk, so Washington should continue protecting them. But when it comes to the commitments to Taiwan and to the South China Sea, the logic of current policy is much less defensible. There is a strong case for cutting back on these commitments.

Concessions on these interests could take a variety of forms. The most attractive type would be a

grand bargain, in which the United States agreed to end its commitment to Taiwan in exchange for China agreeing to resolve its South China Sea disputes with the other claimants. Yet the time for such a geopolitical compromise has passed. China has hardened its positions on the South China Sea and on the U.S. role in East Asia.

Without acknowledging it, U.S. officials are accepting a great deal of risk.

That leaves a less attractive option: the unilateral shedding of U.S. commitments. One form that choice could take is appeasement—concessions that were granted with no expectation of reciprocity and designed to satisfy China’s interest in expansion. Appeasement, however, would now be a bad bet, given that a total U.S. withdrawal from East Asia might be required to satisfy Beijing. A better bet would be

retrenchment. The United States could end its commitment to Taiwan and scale back its opposition to China’s assertive policies simply to avoid conflict.

Washington would be seeking a clear benefit: lowered odds of a crisis or going to war over secondary or tertiary interests. Retrenchment’s success would not depend on whether China’s goals are limited or on whether China agreed with the United States on the purpose of the concessions.

What would this policy look like in practice? The United States would make its revised position public, thereby laying the foundation to minimize pressure from foreign policy elites and the public to intervene if China attacked Taiwan. It would continue to make clear that China’s use of force to conquer Taiwan would violate international norms, and it could even continue to sell arms to Taiwan to make conquest more difficult. Retrenchment need not necessarily entail defense cuts. In fact, Washington could boost spending to preserve and even enhance its capability to defend Japan and South Korea. These investments would send a clear signal to China and to U.S. allies: the United States is determined to protect the commitments it hasn’t cut.

HARD Choices

Under the current strategy of preserving all U.S. commitments in East Asia, the risk of a major war with China is small (although growing). But unlikely events with massive consequences deserve to be taken seriously. The costs of a U.S.-Chinese war would be enormous, even catastrophic were it to go nuclear. And yet policymakers have shown little interest in scaling back the commitments that make such a war imaginable.

Retrenchment may not be getting the hearing it deserves because it clashes with the United States’ self-perception as the global superpower. For those who see the United States as the winner of the Cold War, the creator and leader of the liberal international order, and the protector of much of what is worth protecting, retrenchment is simply too jarring.

This is a dangerous reflex. This attachment to a certain identity could act as a barrier to revising policy, leading the United States to insist on preserving the status quo when its material interests point in the opposite direction. Although China’s rise should not cause the United States to change its values, including respect for democracies, it should prompt it to update its self-image and accept some loss of status.

Most observers appear to believe that the United States is pursuing a cautious policy: after all, it is simply maintaining its existing commitments. Yet a declining power determined to preserve the status quo can in fact be engaging in very risky behavior. This is what the United States is doing today. Without acknowledging it, U.S. officials are accepting a great deal of risk, clinging to old commitments as the balance of power in East Asia shifts.

The burden for sustaining the current policy should lie with its proponents, who should acknowledge the risks and spell out why they are warranted. Without having this debate, the United States will continue, almost on autopilot, to preserve its commitments in the region, even though what is likely called for is a long-overdue change in course.

You are reading a free article.

Posted for fair use

For a declining power, the best option to avoid war may be to cut back on its commitments.

www.foreignaffairs.com

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/WV45PWEYUVKWXCFL4KW725ZAMQ.jpg)