(482) 07-17-2021-to-07-23-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(483)

07-24-2021-to-07-30-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(484) 07-31-2021-to-08-06-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

---------------------------------------

LEBANON FIRES ROCKETS INTO ISRAEL

--------------------

The Winds of War Blow in Korea and The Far East

www.timebomb2000.com

www.timebomb2000.com

--------------------

First Afghan Provincial Capital Falls to Taliban

---------------------

Hummm......

www.businessinsider.com

www.businessinsider.com

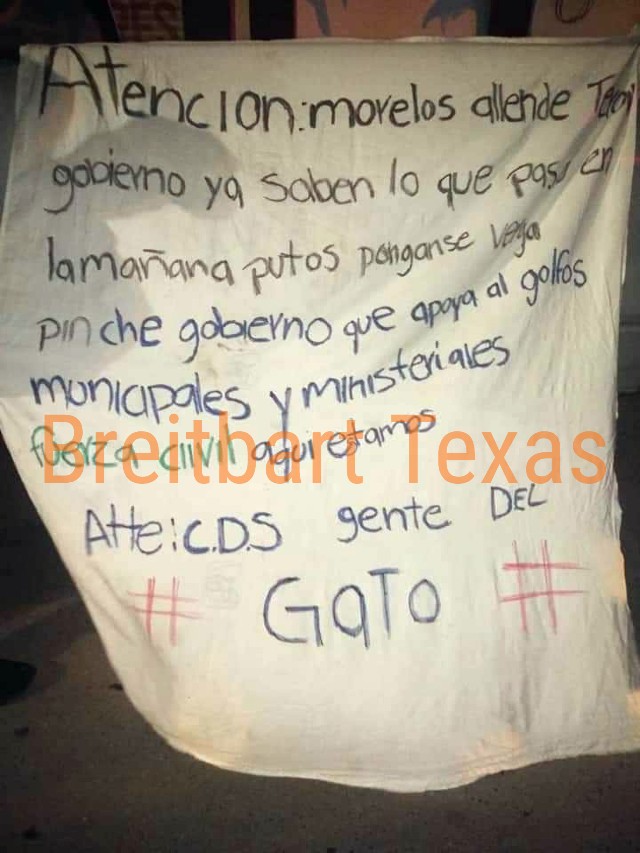

How US intelligence has helped cartels kill thousands in Mexico

Luis Chaparro

19 hours ago

Chihuahua, Mexico — Tens of thousands of people have been killed in Mexico during the "war on drugs," and while turf battles between drug cartels may drive much of the violence, US authorities have helped make some of that bloodshed possible.

The new Netflix feature series "Somos," based on a revealing article by journalist Ginger Thompson, seeks to illuminate the US's role in the massacre in Allende, a town in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila.

Thompson's 2017 article details how in 2011 the Zetas cartel "swept through" Allende and nearby towns "like a flash flood, demolishing homes and businesses and kidnapping and killing dozens, possibly hundreds, of men, women, and children."

The massacre unfolded after the DEA told Mexican authorities of a secret operation to spy on several cellphones belonging to Zetas leaders. Mexican authorities leaked details of the operation to the Zetas, who ordered the killings of everyone suspected of being informants, their families, and anyone who might be close to them.

Among the many victims were locals who had nothing to do with the cartel or with US or Mexican authorities. "They just happened to be in the way," Thompson wrote in 2017.

"I started this story because I was aware that there are many tragedies like the one in Allende, but this one in particular could show a direct link to the US," Thompson told Insider.

For Thompson this was an opportunity to "at least have policymakers thinking" about the consequences of their decisions, but she's not confident the series will lead to better policies.

"I think the story of Allende has sort of been heard in Washington. There are investigations happening as a result of that story. The Mexican government has heard and talked about what happened in Allende as a result of 'Somos,' but we'd be kidding ourselves if we think this will solve the problem," she said.

For members of the Coahuila state police, the Netflix series stirred some obscure memories but was mostly a reminder of what hasn't happened.

"After learning what happened in Allende and watching the series on Netflix the feeling I have is that nothing has changed. Organized crime keeps on top of the game and collud[ing] with most Mexican authorities," a state police intelligence agent told Insider, speaking anonymously since they were not authorized to speak with the media.

Although collaboration between drug cartels and Mexican officials is nothing new, what "Somos" and Thompson's article shed light on is the responsibility the US bears for the murders.

"Unlike most places in Mexico that have been ravaged by the drug war, what happened in Allende didn't have its origins in Mexico. It began in the United States, when the Drug Enforcement Administration scored an unexpected coup," Thompson wrote in the 2017 article.

Mike Vigil, former chief of international operations for the DEA, said that the Allende massacre could have been avoided.

"When you work with or in Mexico you have to be very careful with the information you are sharing. You could end up with a horrific situation like what happened in Allende," said Vigil, who worked in Mexico for almost 20 years.

"I think the DEA made a huge mistake by sharing information, but they've learned from that mistake. Now the ones that have to learn from this are the Mexican government," Vigil told Insider.

US authorities could be linked to another massacre like the one in Allende, especially after Mexico's recent reform of its National Security Law, Vigil said.

"This new law is requiring all foreign agents to report any interaction with Mexico. This means that all of the sensitive information is going to be shared with unknown Mexican officials and could jeopardize not only operations but many lives," he said.

The US and Mexican governments need to work together better, Thompson said, but it is unclear if they can or what would come of it.

"It is hard to know how reliable both governments are on this subject, but what is clear is that this fight is one for both countries. It is both governments' responsibility," she said.

Mexico's defense secretary, Luis Cresencio Sandoval, was in charge of the military garrison in Allende when the massacre took place but has deflected responsibility for failing to stop the killings.

"On March 1, 2011, I officially was assigned to be responsible for this military garrison, but I arrived a few days later and our military responsibilities during those years were not operative but administrative," Sandoval said in July.

Thompson said she is hopeful the series would find a new and broader audience for the story of what happened in Allende, although she is not sure if a news story or a Netflix series could stop such a massacre from happening again.

"I do think the series captures the essence of what happened there, and if we can get the message out there it would be amazing," Thompson said. "I really hope it won't happen again, but I think it is happening now. People are still disappearing. The drug war is still going on. People are still dying."

(483)

07-24-2021-to-07-30-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(484) 07-31-2021-to-08-06-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

---------------------------------------

LEBANON FIRES ROCKETS INTO ISRAEL

--------------------

The Winds of War Blow in Korea and The Far East

ALERT - The Winds of War Blow in Korea and The Far East

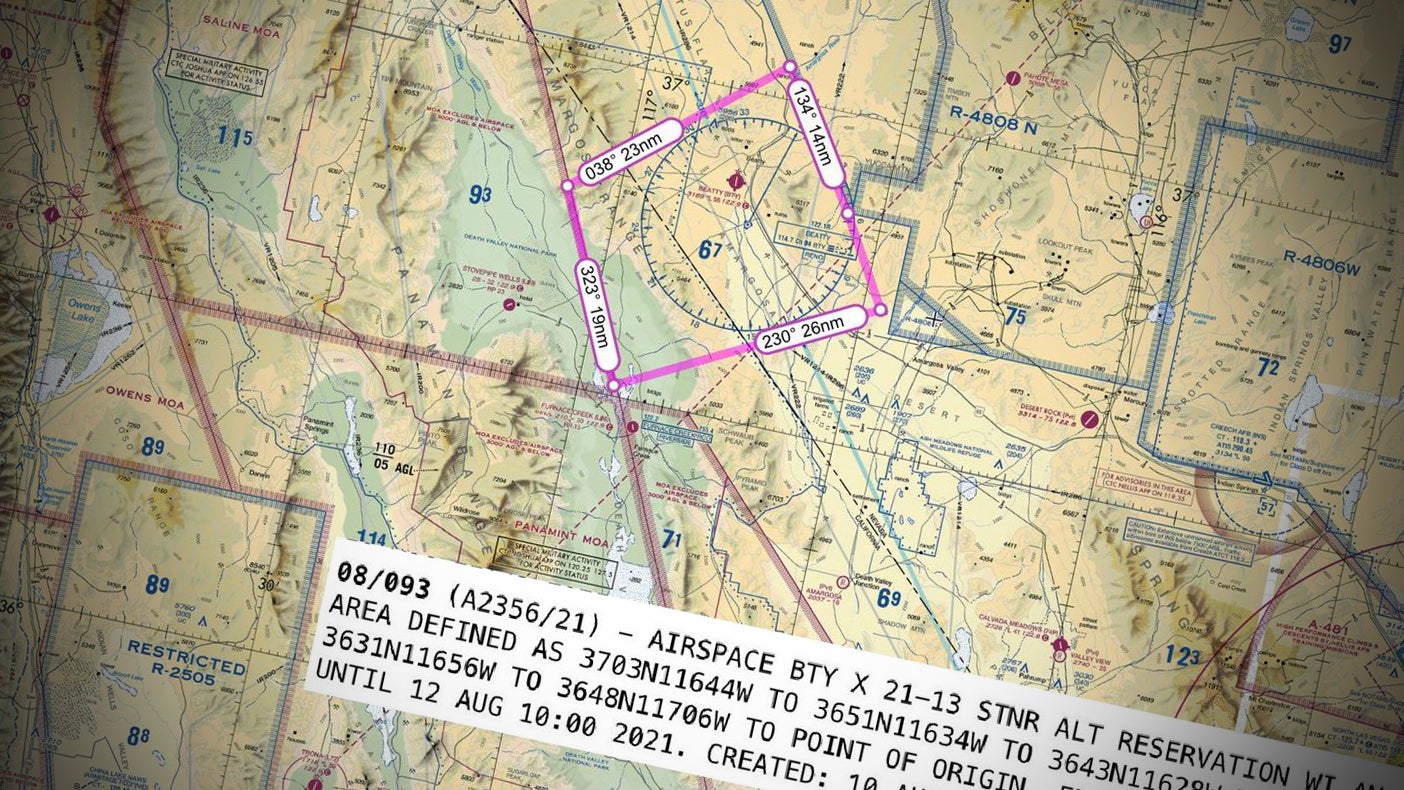

The biggest mobilization of the last 40 years: All U.S. Navy fleets on combat readiness! The largest mobilization of the last 40 years(!) began with the U.S. Navy putting the Fleets on combat readiness. In a move described as "unprecedented" the US Navy is proceeding with a global...

--------------------

First Afghan Provincial Capital Falls to Taliban

---------------------

Hummm......

How US intelligence has helped cartels kill thousands in Mexico

"When you work with or in Mexico you have to be very careful with the information you are sharing," a former DEA official told Insider.

How US intelligence has helped cartels kill thousands in Mexico

Luis Chaparro

19 hours ago

- Drug-related violence has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths in Mexico over the past two decades.

- Criminal groups drive that violence, but US and Mexican authorities have helped make some of it possible.

- "When you work with or in Mexico you have to be very careful with the information you are sharing," a former DEA official said.

Chihuahua, Mexico — Tens of thousands of people have been killed in Mexico during the "war on drugs," and while turf battles between drug cartels may drive much of the violence, US authorities have helped make some of that bloodshed possible.

The new Netflix feature series "Somos," based on a revealing article by journalist Ginger Thompson, seeks to illuminate the US's role in the massacre in Allende, a town in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila.

Thompson's 2017 article details how in 2011 the Zetas cartel "swept through" Allende and nearby towns "like a flash flood, demolishing homes and businesses and kidnapping and killing dozens, possibly hundreds, of men, women, and children."

The massacre unfolded after the DEA told Mexican authorities of a secret operation to spy on several cellphones belonging to Zetas leaders. Mexican authorities leaked details of the operation to the Zetas, who ordered the killings of everyone suspected of being informants, their families, and anyone who might be close to them.

Among the many victims were locals who had nothing to do with the cartel or with US or Mexican authorities. "They just happened to be in the way," Thompson wrote in 2017.

"I started this story because I was aware that there are many tragedies like the one in Allende, but this one in particular could show a direct link to the US," Thompson told Insider.

For Thompson this was an opportunity to "at least have policymakers thinking" about the consequences of their decisions, but she's not confident the series will lead to better policies.

"I think the story of Allende has sort of been heard in Washington. There are investigations happening as a result of that story. The Mexican government has heard and talked about what happened in Allende as a result of 'Somos,' but we'd be kidding ourselves if we think this will solve the problem," she said.

For members of the Coahuila state police, the Netflix series stirred some obscure memories but was mostly a reminder of what hasn't happened.

"After learning what happened in Allende and watching the series on Netflix the feeling I have is that nothing has changed. Organized crime keeps on top of the game and collud[ing] with most Mexican authorities," a state police intelligence agent told Insider, speaking anonymously since they were not authorized to speak with the media.

Although collaboration between drug cartels and Mexican officials is nothing new, what "Somos" and Thompson's article shed light on is the responsibility the US bears for the murders.

"Unlike most places in Mexico that have been ravaged by the drug war, what happened in Allende didn't have its origins in Mexico. It began in the United States, when the Drug Enforcement Administration scored an unexpected coup," Thompson wrote in the 2017 article.

Mike Vigil, former chief of international operations for the DEA, said that the Allende massacre could have been avoided.

"When you work with or in Mexico you have to be very careful with the information you are sharing. You could end up with a horrific situation like what happened in Allende," said Vigil, who worked in Mexico for almost 20 years.

"I think the DEA made a huge mistake by sharing information, but they've learned from that mistake. Now the ones that have to learn from this are the Mexican government," Vigil told Insider.

US authorities could be linked to another massacre like the one in Allende, especially after Mexico's recent reform of its National Security Law, Vigil said.

"This new law is requiring all foreign agents to report any interaction with Mexico. This means that all of the sensitive information is going to be shared with unknown Mexican officials and could jeopardize not only operations but many lives," he said.

The US and Mexican governments need to work together better, Thompson said, but it is unclear if they can or what would come of it.

"It is hard to know how reliable both governments are on this subject, but what is clear is that this fight is one for both countries. It is both governments' responsibility," she said.

Mexico's defense secretary, Luis Cresencio Sandoval, was in charge of the military garrison in Allende when the massacre took place but has deflected responsibility for failing to stop the killings.

"On March 1, 2011, I officially was assigned to be responsible for this military garrison, but I arrived a few days later and our military responsibilities during those years were not operative but administrative," Sandoval said in July.

Thompson said she is hopeful the series would find a new and broader audience for the story of what happened in Allende, although she is not sure if a news story or a Netflix series could stop such a massacre from happening again.

"I do think the series captures the essence of what happened there, and if we can get the message out there it would be amazing," Thompson said. "I really hope it won't happen again, but I think it is happening now. People are still disappearing. The drug war is still going on. People are still dying."