Continued.....

But that is all public relations; there is no legally significant difference between an SOE merchant ship and a privately owned merchant ship, so far as privateering would be concerned. All enemy merchant ships—SOE or otherwise—may be captured, and in some cases destroyed, if located outside neutral territory. Further, for the purpose of determining whether any given vessel is a lawful object of attack, both privately owned merchant vessels and SOE vessels are fair game if they constitute a military objective.14

1. Dean Acheson, “Remarks on the Cuba Quarantine,”

Proceedings of the American Society of International Law, 57th Annual Meeting (1963), 14.

2. Jean Pictet, ed.,

Commentary on the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, vol. 2

: Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea (Geneva, Switzerland: International Committee of the Red Cross, 1960); Second Geneva Convention, article 13(2); Third Geneva Convention, article 4(2).

3. Lassa Oppenheim,

International Law: A Treatise, 8th ed., H. Lauterpacht ed., vol. II:

Disputes, War & Neutrality, 461; James Kraska and Raul Pedrozo,

International Maritime Security Law (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff, 2013), 867; Hisakazu Fujita,

The Law of Naval Warfare, Natalino Ronzitti ed. (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff, 1988), 68, 70.

4. Sir Francis Taylor Piggott,

The Declaration of Paris, 1856: A Study, Documented (London: University of London Press ltd., 1919), 142–49; Carlton Savage,

Policy of the United States toward Maritime Commerce in War, vol. I:

1776–1914 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1935), 76–81, 89–90.

5. “The

Marie Glaeser,”

Times Legal Reports 31 (1914), 1, 10; William McKinley, “Proclamation 413—Standards of Conduct and Respect of Neutral Rights in the War with Spain.”

6. Piggott,

The Declaration of Paris, note 4 at 154–61, 206–13.

7. U.S. House of Representatives, 55th Congress, 3rd Session,

Papers Related to the Foreign Relations of the United States (Serial Set 3743) (Washington, DC: GPO, 1901), 1170–71; J. B. Moore,

A Digest of International Law, vol. 7 (Washington, DC: 1906), 541–42; Charles H. Stockton,

The Declaration of Paris, 14; American Society of International Law,

American Journal of International Law 14 (1920), 356, 362, 367.

8. President Franklin Pierce,

Second Annual Message to Congress, 4 December 1854.

9. See John B. Bellinger III and William J. Haynes II, “A U.S. Government Response to the International Committee of the Red Cross Study

Customary International Humanitarian Law,”

International Review of the Red Cross 89 (2007): 443 at n. 4; “Principles Applicable to the Formation of General Customary International Law,” International Law Association (ILA),

Report of the Sixty-Ninth Conference (London: 2000), Principle 14, Commentary, paragraph (e), 26.

10. ILA, note 9 at Principle 15, 27–29.

11. “Letter of Mr. Marcy, Sec. of State, to Mr. Sartiges,” 28 July 1856, in

Miscellaneous Documents of the U.S. Senate (Washington, DC: GPO, 1886); U.S. Congress,

An Act Concerning Letters of Marque, Prizes, and Prize Goods, chapter 85 (3 March 1863).

12. James Brown Scott,

The Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907: A Series of Lectures Delivered before the Johns Hopkins University in the Year 1908, vol. 2 (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1909), 222–23.

13. Franklin D. Roosevelt,

Message to Congress on the Arming of Merchant Ships, 9 October 1941.

14. DoD,

Law of War Manual, note 1 at §5.7 and §13.5.2.

----

Posted for fair use.....

The threat of privateers to China’s maritime economy could strengthen deterrence and possibly prevent a war.

www.usni.org

Unleash the Privateers!

The United States should issue letters of marque to fight Chinese aggression at sea.

By Colonel Mark Cancian, U.S. Marine Corps (Retired) and Brandon Schwartz

April 2020

Proceedings

Vol. 146/4/1,406

For a discussion of the law regarding letters of marque, see: U.S. Privateering Is Legal

Naval strategists are struggling to find ways to counter a rising Chinese Navy. The easiest and most comfortable course is to ask for more ships and aircraft, but with a defense budget that may have reached its peak, that may not be a viable strategy. Privateering, authorized by letters of marque, could offer a low-cost tool to enhance deterrence in peacetime and gain advantage in wartime. It would attack an asymmetric vulnerability of China, which has a much larger merchant fleet than the United States. Indeed, an attack on Chinese global trade would undermine China’s entire economy and threaten the regime’s stability. Finally, despite pervasive myths to the contrary, U.S. privateering is not prohibited by U.S. or international law.

What are Letters of Marque?

Privateering is not piracy—there are rules and commissions, called letters of marque, that governments issue to civilians, allowing them to capture or destroy enemy ships.1 The U.S. Constitution expressly grants Congress the power to issue them (Article I, section 8, clause 11). Captured vessels and goods are called prizes, and prize law is set out in the U.S. Code. In the United States, prize claims are adjudicated by U.S. district courts, with proceeds traditionally paid to the privateers.2 (“Privateer” can refer to the crew of a privateering ship or to the ship itself, which also can be referred to as a letter of marque).

Congress would likely set policy—for example, specifying privateer targets, procedures, and qualifications—then authorize the President to oversee the privateering regime.3 Congress also could indemnify privateers from certain liabilities and curb the potential for abuse and violations of international law through surety bonds and updated regulations on conduct.

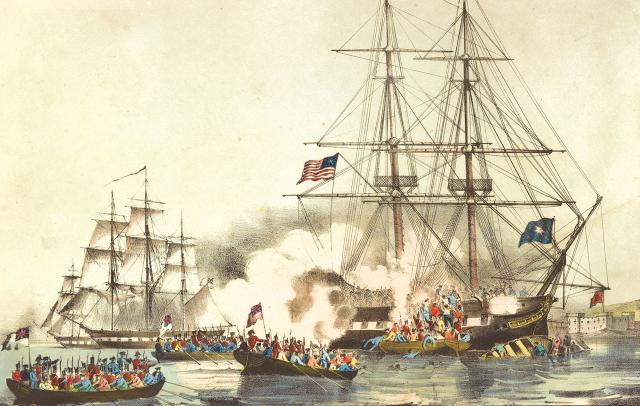

Letters of marque could be issued quickly, with privateers on the hunt within weeks of the start of a conflict. By contrast, it would take four years to build a single new combatant for the Navy. During the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, privateers vastly outnumbered Navy ships, with one U.S. official calling privateers “our cheapest and best navy.”4 Though many were lost, thousands sailed and disrupted British trade.5 British officials complained they could not guarantee the safety of civilian trade.

Privateering constitutes a once universally accepted but now thoroughly unconventional way of harnessing the private sector in war.

A Rising Chinese Navy

The rise of the Chinese military has been well documented, but a few points highlight why privateering would be a useful element of U.S. naval strategy.

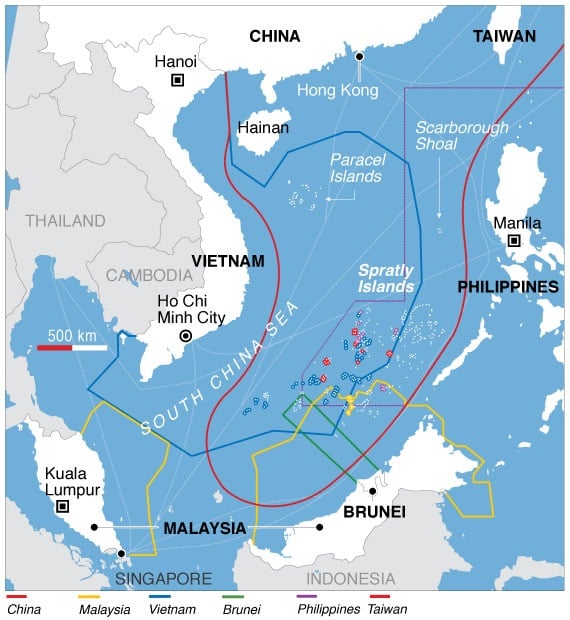

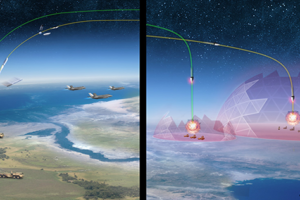

China has built a powerful defensive network around its homeland, sometimes called an antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) envelope. As one element of this strategy, China has expanded its navy from a modest coastal force in the 1980s to an oceangoing force of at least 200 ships, with sophisticated air defenses, antiship missiles, and even aircraft carriers. Backing up the navy are land-based missiles and bombers.

Cracking open such a defense would require a naval campaign more demanding than anything the U.S. Navy has done in the past 70 years, leaving little capability for other tasks, such as hunting down China’s global merchant fleet. Whatever limited naval forces might be left over from a campaign in the Pacific would be needed to keep an eye on other potential adversaries, such as Russia, Iran, or North Korea.

Asymmetric Vulnerabilities

A print showing the U.S. privateer General Armstrong under attack by HMS Plantagenet, a 74-gun British ship of the line, in 1814. Though it has been two centuries since the U.S. government issued letters of marque, the prospect of a fight in the western Pacific makes this a good time to reconsider their use.

Library of Congress

China has aggressively expanded its global economic and diplomatic influence through its Belt and Road Initiative, but this expansion creates a vulnerability, as these investments must be protected. Chinese vulnerability goes deeper. China’s economy has doubled in the past 15 years, driven by exports carried in Chinese hulls. Thirty-eight percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) comes from trade, against only 9 percent of U.S. GDP.6 Chinese social stability is built on a trade-off: The Chinese Communist Party has told the people they will not have democratic institutions, but they will receive economic prosperity.

China’s merchant fleet is large, because the cost to China of building and operating merchant ships is low, and its export-driven economy creates a huge demand. In 2018, China had 2,112 ships in its global merchant fleet and Hong Kong had another 2,185.7 In addition, China has a massive long-distance fishing fleet, estimated at 2,500 vessels.8

By contrast, the United States has only 246 ships in its merchant fleet. That fleet—expensive to build and operate—is sustained mainly by the Jones Act, which mandates that ships conveying cargo between U.S. ports must be U.S.-flagged.

This asymmetric vulnerability gives the United States a major strategic advantage. The threat privateering poses to the Chinese economy—and hence the Communist Party—could provide the United States with a major wartime advantage and enhance peacetime deterrence, thus making war less likely. Even if China threatens to dispatch its own privateers, U.S. vulnerability is comparatively small.

Size of the Dog in the Fight

The ordinary course of action would be to have U.S. Navy warships drive China’s merchant fleet from the seas. However, the U.S. Navy would have its hands full taking on the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). The U.S. fleet is down to about 295 ships, and though it may reach and surpass 340 in the early 2040s before declining again, the goal of 355 ships is probably out of reach.9 A conflict with China would likely require this entire fleet; indeed, against a capable PLAN adversary defending its home waters, even 355 ships might be too few.

By contrast, in World War II, the U.S. Navy grew to 6,700 ships, counting neither Great Britain’s huge fleet nor contributions from other allies.10 And the allies, Britain and France particularly, had a global network of colonies that denied adversaries sanctuary and provided bases for operations against enemy ships. Comparable assets will not be available in a future conflict. Indeed, some former allies and colonies might even give sanctuary to Chinese vessels.11

Cruise the Seas for Chinese Gold

Capitalizing on Chinese vulnerabilities requires large numbers of ships, and the private sector could provide them. The ocean is large, and there are thousands of ports to hide in or dash between. While the Navy could not afford to have a multibillion-dollar destroyer sitting outside Rio de Janeiro for weeks waiting for Chinese vessels to leave, a privateer could patiently wait nearby as U.S. diplomats put pressure on (presumably neutral) Brazil.

Neither recruiting crews nor the need to arm ships would constitute a major obstacle. Privateers do not need to be heavily armed, because they would be taking on lightly (or un-) armed merchant vessels, choosing vulnerable targets, or acting cooperatively with other privateers. Since the goal is to capture the hulls and cargo, privateers do not want to sink the vessel, just convince the crew to surrender. How many merchant crews would be inclined to fight rather than surrender and spend the war in comfortable internment?12

The existing private military industry would doubtless jump at the chance to privateer. Dozens of companies currently provide security services, from the equivalent of mall guards to armed antipiracy contingents on ships. A large pool of potential recruits has shown willingness to work for private contractors. At the height of the Iraq War, for example, the United States employed 20,000 armed contractors in security jobs.

In fact, private security vessels already have been created, demonstrating the concept’s viability. The private security firm Blackwater outfitted an armed patrol craft to defend commercial shipping from Somali pirates.13 At the height of Somali piracy, there were some 2,700 armed contractors on ships and 40 private armed patrol boats operating in the Indian Ocean region.14

Just as the prospect of prize money induced thousands of seamen to sign on with privateers during the Revolution and the War of 1812, similar inducements—such as the prospect of earning millions of dollars from a single capture—would attract the needed personnel in a future conflict.

New Approaches Required

The notion of privateering makes naval strategists uncomfortable because it is an approach to war that does not conform to the way the U.S. Navy has fought since 1815. There is no modern experience of their use, and there are legitimate concerns about legal foundations and international opinion. But strategists cannot argue for out-of-the-box thinking to face the rising challenge of China and then revert to conventional solutions because out-of-the-box thinking makes them uncomfortable.

As the strategic situation is new, so must our thinking be new. In wartime, privateers could swarm the oceans and destroy the maritime industry on which China’s economy—and the stability of its regime—depend. The mere threat of such a campaign might strengthen deterrence and thereby prevent a war from happening at all. In strategy, as elsewhere, everything old shall be new again.

1. Department of Defense (DoD),

Law of War Manual (2016), § 13.5.2; Louise Doswald-Beck, ed.,

San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea (International Institute of Humanitarian Law, 1995), Rules 13(i), 40–41, 59–60, 135, 138–39.

2. 10 USC § 8852. For prize law, see 10 USC §§ 8851–81, and 10 USC § 7668 (allowing courts to only pay net proceeds into the Treasury).

3. U.S. Congress,

An Act Concerning Letters of Marque, and Prizes, chapter 102, 26 June 1812.

4. Donald R. Hickey,

The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1989), 96

5. Edgar Stanton Maclay,

A History of American Privateers (London: Sampson, Low, Marston, and Co., 1900), 506; George F. Emmons,

The Navy of the United States: from the Commencement, 1775, to 1853 (Washington, DC: 1853), 170–203.

6.

World Bank Trade Database, data.worldbank.org.

7. “Merchant Marine” in

CIA Factbook 2018 (Washington, DC: 2018).

8. Gary Doyle, “

Chinese Trawlers Travel Farthest and Fish the Most: Study,” Reuters, 22 February 2018.

9. Congressional Budget Office

, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2019 Shipbuilding Plan (19 October 2018).

10. Naval History and Heritage Command, “

U.S. Ship Force Levels 1886–Present,”

www.history.navy.mil.

11. MAJ Nicholas R. Nappi, USMC, “

But Will They Fight China?” U.S. Naval Institute

Proceedings 144, no. 5 (May 2018).

12. DoD,

Law of War Manual, note 1 at §13.5.3.

13. Kim Sangupta, “

Blackwater Gunboats Will Protect Ships,”

The Independent, 19 November 2008.

14. Sean McFate,

The Modern Mercenary: Private Armies and What They Mean for World Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 142.

---------

With the number of hulls available to them (never mind domestic politics and legal issues), IMHO Beijing doing this is more likely than the other way around. HC