jward

passin' thru

Afghanistan: US offers to pay relatives of Kabul drone attack victims

Published

18 minutes ago

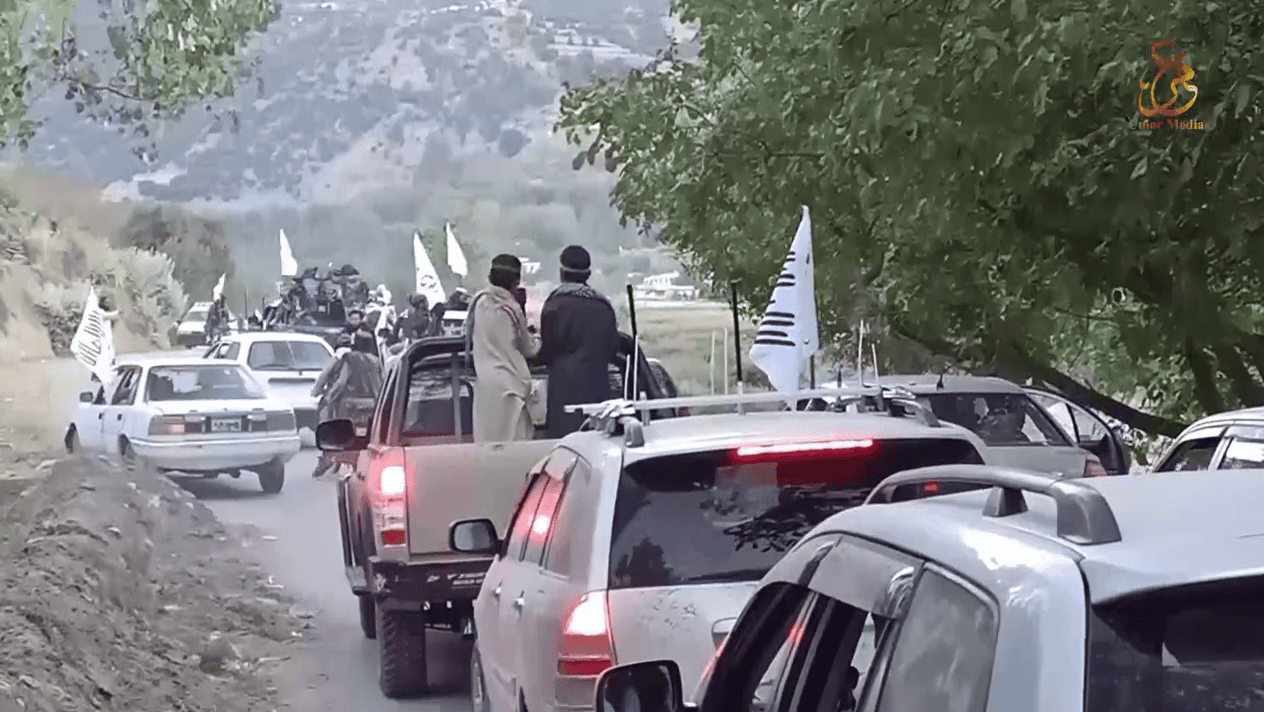

Image caption, The aftermath of the drone strike in the Afghan capital, Kabul

The US government has offered financial compensation to the relatives of 10 people mistakenly killed by the American military in a drone strike on the Afghan capital, Kabul, in August.

An aid worker and nine members of his family, including seven children, died in the strike.

The Pentagon said it was also working to help surviving members of the family relocate to the US.

The strike took place days before the US military withdrew from Afghanistan.

It came amid a frenzied evacuation effort following the Taliban's sudden return to power and only days after a devastating attack close to Kabul's airport by IS-K, a local branch of the Islamic State (IS) group.

US intelligence had tracked the aid worker's car for eight hours on 29 August, believing it was linked to IS-K militants, US Central Command's Gen Kenneth McKenzie said last month.

The investigation found the man's car had been seen at a compound associated with IS-K, and its movements aligned with other intelligence about the terror group's plans for an attack on Kabul airport.

At one point, a surveillance drone saw men loading what appeared to be explosives into the boot of the car, but these turned out to be containers of water.

Gen McKenzie described the strike as a "tragic mistake" and added that the Taliban had not been involved in the intelligence that led to the strike.

The strike happened as the aid worker - named as Zamairi Ahmadi - pulled into the driveway of his home, 3km (1.8 miles) from the airport.

The explosion set off a secondary blast, which US officials initially said was proof that the car was indeed carrying explosives. However, an investigation found it was most likely caused by a propane tank in the driveway.

One of those killed, Ahmad Naser, had been a translator with US forces. Other victims had previously worked for international organisations and held visas allowing them entry to the US.

Media caption, Emal Ahmadi: "Ten people died here... including my daughter, she was two years old"

The compensation offer was made on Thursday in a meeting between Colin Kahl, the under-secretary of defence for policy, and Steven Kwon, the founder and president of an aid group active in Afghanistan called Nutrition and Education International, the Pentagon said in a statement.

Mr Kahl noted Mr Ahmadi and others who were killed "were innocent victims who bore no blame and were not affiliated with ISIS-K or threats to US forces", said a statement attributed to Defence Department spokesman John Kirby.

He reiterated Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin's commitment to the families, including "condolence payments".

Mr Austin has apologised for the botched attack, but Mr Ahmadi's 22-year-old nephew Farshad Haidari said that was not enough.

"They must come here and apologise to us face-to-face," he told the AFP news agency in Kabul.

When the US started to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan, the Taliban managed to seize control of the country within about two weeks in a rapid offensive. Kabul fell on 15 August.

It sparked a mass evacuation effort from the US and its allies, as thousands of people tried to flee. Many were foreign nationals or Afghans who had worked for foreign governments.

The security situation was further heightened after the IS-K attack on the airport. A suicide bomber killed up to 170 civilians and 13 US troops outside the airport on 26 August.

Many of those killed had been hoping to board evacuation flights leaving the city.

The last US soldier left Afghanistan on 31 August - the deadline President Joe Biden had set for the US withdrawal.

More than 124,000 foreigners and Afghans were flown out of the country beforehand. But some people were unable to get out in time, and evacuation efforts are ongoing.

video on site

www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

Published

18 minutes ago

Image caption, The aftermath of the drone strike in the Afghan capital, Kabul

The US government has offered financial compensation to the relatives of 10 people mistakenly killed by the American military in a drone strike on the Afghan capital, Kabul, in August.

An aid worker and nine members of his family, including seven children, died in the strike.

The Pentagon said it was also working to help surviving members of the family relocate to the US.

The strike took place days before the US military withdrew from Afghanistan.

It came amid a frenzied evacuation effort following the Taliban's sudden return to power and only days after a devastating attack close to Kabul's airport by IS-K, a local branch of the Islamic State (IS) group.

US intelligence had tracked the aid worker's car for eight hours on 29 August, believing it was linked to IS-K militants, US Central Command's Gen Kenneth McKenzie said last month.

The investigation found the man's car had been seen at a compound associated with IS-K, and its movements aligned with other intelligence about the terror group's plans for an attack on Kabul airport.

At one point, a surveillance drone saw men loading what appeared to be explosives into the boot of the car, but these turned out to be containers of water.

Gen McKenzie described the strike as a "tragic mistake" and added that the Taliban had not been involved in the intelligence that led to the strike.

The strike happened as the aid worker - named as Zamairi Ahmadi - pulled into the driveway of his home, 3km (1.8 miles) from the airport.

The explosion set off a secondary blast, which US officials initially said was proof that the car was indeed carrying explosives. However, an investigation found it was most likely caused by a propane tank in the driveway.

One of those killed, Ahmad Naser, had been a translator with US forces. Other victims had previously worked for international organisations and held visas allowing them entry to the US.

Media caption, Emal Ahmadi: "Ten people died here... including my daughter, she was two years old"

The compensation offer was made on Thursday in a meeting between Colin Kahl, the under-secretary of defence for policy, and Steven Kwon, the founder and president of an aid group active in Afghanistan called Nutrition and Education International, the Pentagon said in a statement.

Mr Kahl noted Mr Ahmadi and others who were killed "were innocent victims who bore no blame and were not affiliated with ISIS-K or threats to US forces", said a statement attributed to Defence Department spokesman John Kirby.

He reiterated Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin's commitment to the families, including "condolence payments".

Mr Austin has apologised for the botched attack, but Mr Ahmadi's 22-year-old nephew Farshad Haidari said that was not enough.

"They must come here and apologise to us face-to-face," he told the AFP news agency in Kabul.

When the US started to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan, the Taliban managed to seize control of the country within about two weeks in a rapid offensive. Kabul fell on 15 August.

It sparked a mass evacuation effort from the US and its allies, as thousands of people tried to flee. Many were foreign nationals or Afghans who had worked for foreign governments.

The security situation was further heightened after the IS-K attack on the airport. A suicide bomber killed up to 170 civilians and 13 US troops outside the airport on 26 August.

Many of those killed had been hoping to board evacuation flights leaving the city.

The last US soldier left Afghanistan on 31 August - the deadline President Joe Biden had set for the US withdrawal.

More than 124,000 foreigners and Afghans were flown out of the country beforehand. But some people were unable to get out in time, and evacuation efforts are ongoing.

video on site

Afghanistan: US offers to pay relatives of Kabul drone attack victims

Ten people were mistakenly killed by the US military in a drone strike on the Afghan capital.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/GF2OBV7ASBI3DG3W4LE7UZ7BLI.jpg)