How one powerful family wrecked a country

Ishaan Tharoor

7-9 minutes

You’re reading an excerpt from the Today’s WorldView newsletter. Sign up to get the rest, including news from around the globe, interesting ideas, and opinions to know sent to your inbox every weekday.

There are falls from grace and then there’s what’s happening to Mahinda Rajapaksa in Sri Lanka. For the better part of the past two decades, he loomed large over the island nation’s politics — first as president for a decade between 2005 and 2015 and then, after a brief interregnum, as prime minister in a government where his brother, Gotabaya, served as president. The Rajapaksa clan had its hands on various apparatuses of state, from exerting control over the security forces to commanding influence over major sectors of the economy.

The first part of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s years in power were defined by his ruthless defeat of the long-running Tamil Tiger insurgency; in the latter years, the populist quasi-autocrat, who seemed at times to style himself as

an uncrowned warrior king, leaned heavily into majoritarian nationalist politics aimed at courting the votes of Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese Buddhist majority. A defeat in presidential elections in 2015 seemed to signal a political ebb for the Rajapaksa family, but they came roaring back to power in the wake of

the deadly Easter Sunday terrorist attacks in 2019, campaigning on their supposed national security bona fides.

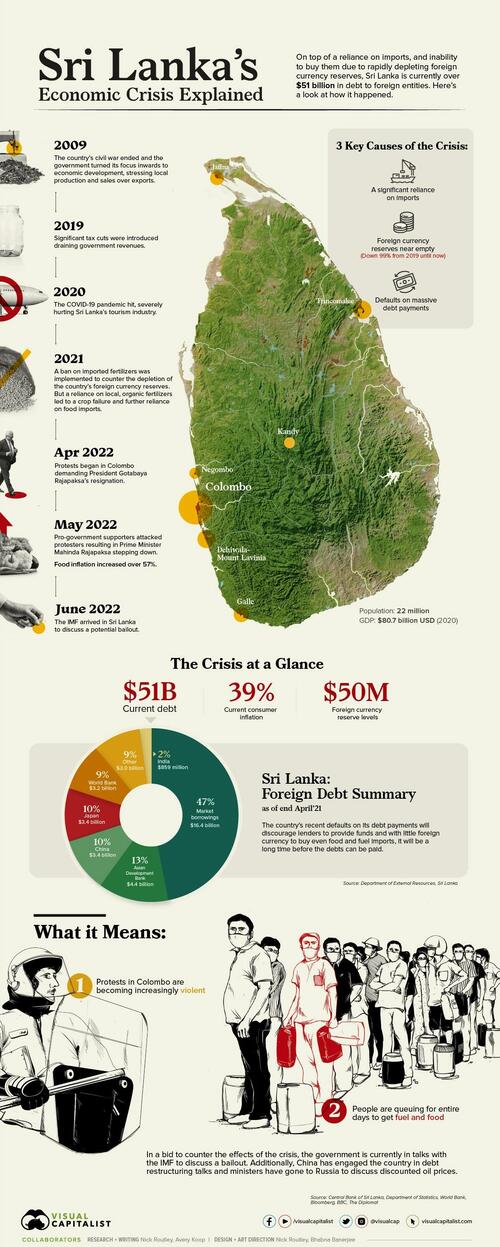

Now, their era of dominance could be finally coming to a close. Sri Lanka is in the grips of the worst economic crisis in its history as an independent country. A

cascading set of woes — including spiraling inflation, deepening government debt and emptying foreign exchange coffers — meant that the country has struggled to import basic essential goods, while prices for food and fuel have skyrocketed over the past year. Power cuts have blanketed the nation of 22 million people in darkness. Shortages of medicines and medical equipment led some aid groups to liken the situation in Sri Lankan hospitals to

a humanitarian disaster.

Following weeks of mass protests against his government, as well as deadly violence in the streets on Monday, Rajapaksa was

compelled to resign his post as prime minister. His capitulation made him the fourth member of his family to give up a high-powered role in the space of a month — following his brothers Basil and Chamal (now former ministers of finance and irrigation, respectively) and his son Namal (former minister of sports and youth affairs). The attention falls on President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the biggest link in a long nepotistic chain.

For days across the country, the largely peaceful demonstrations have pulled in irate Sri Lankans from all walks of life. In Colombo, they gathered at a popular waterfront promenade known as Galle Face and turned it into

a kind of Tahrir Square on the Indian Ocean, a carnival of activism replete with tent encampments, makeshift public libraries, and health and food facilities. Their message was clear: They would go only after the Rajapaksas did.

On Monday, pro-government supporters likely bused into the city by Rajapaksa and his allies violently attacked the site at Galle Place and protesters elsewhere in the capital. That assault,

my colleagues reported, “triggered a wave of furious retaliation. Vigilantes poured into the streets, chased and beat government loyalists, erected their own checkpoints on roads, and burned down homes owned by the Rajapaksas and their allies. By Tuesday morning, the former prime minister had reportedly fled to a military base in the country’s northeast, which was soon surrounded by angry citizens.”

The mood in the country is uneasy: Gotabaya is struggling to hold on politically, urging an interim unity government that few members of the opposition wish to now join as long as he remains in power. All the while, Sri Lankan negotiators are scheduled to begin talks with the International Monetary Fund this week. The country defaulted on its debts last month — a victim, to a certain extent, of

the global disruptions sparked by both the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Analysts say the uncertainty around the country’s leadership is clouding any possibility of economic recovery. “The political situation has to be resolved before anything can happen,” Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, executive director of the Center for Policy Alternatives in Colombo,

told my colleagues. “You need a credible government. The presidency right now is a poisoned chalice.”

Rajapaksa’s critics would argue that much of that poisoning is his family’s fault. That includes widespread and documented

allegations of human rights abuses and war crimes that accompanied the Sri Lankan military’s 2009 offensive against Tamil rebels, where thousands of civilians were killed in the final stages of the war; years of violence toward and

intimidation and harassment of journalists and civil society groups; and

the stoking of ethno-religious tensions, including the tacit cultivation of orders of extremist militant Buddhist monks, who have launched attacks on the country’s minorities.

Then there was their mismanagement of the economy. The Rajapaksas expanded funding for the military even in peacetime and engaged in

a form of crony capitalism that likely enriched the family’s fortunes. They touted major Chinese-funded infrastructure projects — including a port in their family’s hometown of Hambantota — that not only turned into wasteful white elephants, but made Sri Lanka into one of the world’s leading exhibits of what happens

when a nation gets indebted to Beijing.

The roots of the current crisis, critics argue, predated both the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. “No serious observer

believed the country was going to be able to pay back the $29 billion in debts it owed over the next five years, or the nearly $7 billion in debt it owed this year,”

wrote Amita Arudpragasam in Foreign Policy. “But Sri Lanka’s government, filled with Rajapaksa family members and loyalists, was buttressed by Sinhalese Buddhist supremacists, crony capitalists, the state-owned media, and some influential private media houses. It continued to gaslight its people.”

The vehemence and endurance of the protest movement seems to suggest that gaslighting is no longer working. “The organic growth of the protest and its scale showed that the Rajapaksas were no longer the popular political family that they once were,”

wrote Sri Lankan journalist Dilrukshi Handunnetti for the Wire, an Indian online publication. “In addition to calls for collective resignations were demands for forensic audits, recovery of stolen assets and legal action against Rajapaksas. People faulted the family for the island’s state of bankruptcy.”

There are troubled times ahead, as the country grapples with both political dysfunction and profound economic pain. “In Sri Lanka, we were an extremely divided country, not in a facile sense, but because of decades of war and ethnic violence and deep cruelty toward each other in many ways,” Sharika Thiranagama, an anthropologist at Stanford University, told me.

But she described the protests as a source of hope and solidarity. “This is what a democratic mobilization can look like. … It’s people demanding accountability for corruption, demanding basic rights to dignity,” she said. “This is something that has been very nourishing at a really bad time.”