Yes to be accurate the title should read "WWII-Era reminiscent" but at least the narrative of the article is pretty inclusive, though it begs the question of why not either build a new turboprop version of the Skyraider (without the counter-rotating prop problems of the Skyshark) or the twin engine Bronco since they're both prominently mentioned in the article......

For links see article source.....

Posted for fair use.....

http://motherboard.vice.com/read/low-and-slow

Motherboard

Newsletter

- All Fronts -

The WWII-Era Plane Giving the F-35 a Run for Its Money

Written by John Ismay, Adrian Bonenberger, and Damien Spleeters

September 18, 2015 // 08:15 AM EST

On December 5, 2001, an American B-52 flying tens of thousands of feet above the ground mistakenly dropped a 2,000-pound satellite-guided bomb on an Army Special Forces team in Afghanistan. The aircrew had been fed the wrong coordinates, but had the plane been flying as low and slow as older generations of attack planes did, the crew might’ve realized their error simply by looking down at the ground.

It was not long after the Twin Towers fell, and American soldiers were killed in Afghanistan by an American bomb dropped by an American plane. That this mistake happened illustrates just how poorly the air campaign in the United States’ longest war was executed, and how efforts ultimately failed to make things better by going after high-tech solutions that aren’t what they’re cracked up to be compared to the old tried and true technology.

That bomber was on a 30-plus hour round trip flight from the remote island of Diego Garcia, 900 miles south of India. The plane those Green Berets really needed, the low-and-slow flying A-10 Warthog, wasn’t available yet in Afghanistan. Famously rugged and even more famously lethal, the Warthog was the first American jet to actually land at the decrepit Bagram Airfield. Soon after the runway was repaired, many dozens of F-15, F-16, and F/A-18 fighter jets—wholly different creatures—came streaming in.

According to former Defense Department official Pierre Sprey, the US Air Force could have left those other jets out, had they sent three full squadrons of A-10s—72 planes total—to Afghanistan instead. But Sprey says the Air Force “never had more than 12 Warthogs in-country at any given time during the entire war.”

“The A-10 is the best ‘close attack’ plane ever made, period,” Sprey tells me. “But the Air Force hates that mission. They’ll do anything they can to kill that plane.” He says retiring the iconic A-10, a twin-engine attack jet with 30-mm cannons that hit with 14 times the kinetic energy of the 20-mm guns mounted on America’s current fleet of supersonic fighters, became an article of faith among high ranking Air Force officers, generations of whom had been raised to believe in the redemptive power of technological innovation.

They wanted something with more punch. More lethality. They soon found a plane built for exactly this purpose.

That mentality drove production of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the world’s first $1 trillion weapons system. Development of the F-35 was going on in the background throughout the Afghan War despite mountains of evidence that the stealthy jet would never be able to attack ground targets like the A-10 could. Far away from the fighting, the generals in Washington, DC supported the F-35 because they believed “more technology is always better.”

This same thinking drove the push for armed drones over Afghanistan too. But no matter their technological wizardry, remote-piloted hunter-killer aircraft like the Predator and Reaper were arguably even worse at helping ground troops than even the highest-tech manned jets.

So if the A-10 was never going to be around in enough numbers, what could be done? Only one group had enough distance from the Air Force and enough independent money to consider a viable alternative: buying a cheap, lightweight attack plane on their own. That was the Navy SEALs. A group of them met with the Secretary of the Navy in 2006 to tell him about the problems they faced with getting good enough air support.

Like other American combat troops in Afghanistan, the SEALs sometimes found that high-tech gear couldn’t reliably get the job done, or that cheaper, lower-tech solutions worked better. This is how the US military almost adopted the A-29 Super Tucano, a $4 million turboprop airplane reminiscent of WWII-era designs that troops wanted, commanders said was “urgently needed,” but Congress refused to buy.

RISE OF THE SUPER TUCANO

The Super Tucano was a throwback to a bygone era of aerial combat—a time when pilots looked through the blur of a propeller and pointed their nose at the enemy before pulling the trigger. A time before auto-pilot, guided missiles, and infrared gun “pods.” The A-29 was fast enough to get to a fight quickly and light enough to stay there in a low, slow orbit overhead the battle.

Philosophically, the Super Tucano occupies a sort of middle ground between the United States’ two main gunships. As a plane, the A-29 could reach altitudes over the Hindu Kush higher than the AH-64 Apache helicopter, and remain overhead for hours before refueling like the legendary AC-130 Spectre gunships.

But the Spectre only flew at night. By day, Super Tucano’s tight turning radius and low stall speed meant pilots could maintain constant visual contact with ground forces and instantly shift from surveillance and reconnaissance to attack. And after dark, an A-29 could use night vision and thermal sensors as sophisticated as those on any fighter jet.

“It’s a great plane,” says recently retired Air Force Lt. Col. Shamsher Mann, an F-16 pilot who has flown A-29s. “Pilots love it. It handles beautifully, sips gas, and can go anywhere. If you want to get into the fight and mix it up with the guys on the ground, the Super T is a great platform.”

Another former fighter pilot tells me that the Super Tucano provided the “low-end” air-to-ground attack capability the United States simply never had in Afghanistan—a capability the Pentagon’s F-35 could never hope to replicate.

Soon after 9/11, the pilot said, Army Special Forces famously rode horses into the Hindu Kush, but carried laptop computers and sophisticated targeting and communications gear with them as well. “Super Tucano is almost a mirror image of that in the air,” he said. “The low-tech combined with the high-tech.”

Now, five years after Congress killed the A-29 program, with the US Air Force considering a lower-tech replacement for the Warthog, the sad story of the Super Tucano feels more relevant than ever.

An A-29 Super Tucano spinning up. Photo: Senior Airman Ryan Callaghan/USAF

When former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld famously said of the Iraq invasion that “you go to war with the army you have” he also described how the United States started its fight in Afghanistan too.

Supersonic fighters, strategic bombers, and heavy attack helicopters developed to fight the Soviets succeeded in displacing the Taliban and knocking out Saddam Hussein, but proved incredibly cost-ineffective in the insurgencies that followed. Rather than take a step back to evaluate what was best suited for war in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Pentagon doubled down on big-ticket procurement items more suitable for large conventional wars than fighting insurgencies.

In America’s post-9/11 wars, however, the main combat role for tactical aircraft was something called “close air support,” where planes and helicopters are called in to wipe out enemy troops actively shooting at American ground forces. This enemy didn’t have tanks, planes, or helicopters. Sometimes it had motorcycles and pickup trucks. More often it was just people on foot, hiding in houses, in caves, or behind rocks or trees.

In Afghanistan, US troops didn't need airplanes that could evade detection from enemy radar; they needed planes that flew low enough for pilots to see the enemy eye-to-eye. They needed bombs dropped close enough to hurt them, bullets shot from the sky landing just out of arm's reach and into the enemy. They needed the Taliban dead.

When US troops were under fire, they needed aircraft that could stay through the fight, be accurate, and be deadly. Often times, troops needed ordnance “danger close”—generally inside of 500 meters from their own positions—and they’d rather have a pilot down low walk those shots in by eye than risk getting killed by an errant bomb dropped from a high-tech jet from 30,000 feet up, where a pilot can’t even see the target.

But for decades the arrow of progress had firmly pointed toward building and buying higher-tech planes. This would be an uphill battle pitting the worst-case scenario conventional war we might have to fight in the future against the insurgent war we were actually in now.

The Air Force insisted it would have to retire the Warthog fleet to pay for the world’s most expensive plane, the F-35. A plane which, incidentally, can’t fly or fight very well, so much so that the Air Force watered the fighter jet program down to save face. And the Air Force Chief of Staff recently begged off a comparison between the F-35 and A-10 as a “silly exercise,” probably because he knows just how badly the Joint Strike Fighter would fare head-to-head.

Political infighting like this led to poor air support in Afghanistan. And by 2006, a group of SEALs in Afghanistan were fed up with it. They asked the Secretary of the Navy personally for his help in getting a better plane overhead.

Not long after the SEALs’ request, the Secretary put together a small team and charged them with finding a better aircraft for this kind of war. Consensus quickly grew around a lightweight turboprop-driven plane. The team took possession of a couple old Vietnam-era OV-10 Broncos that last saw combat in Desert Storm, and started flying them. But they wanted something with more punch. More lethality. They soon found a plane built for exactly this purpose.

The classified Imminent Fury project was born.

“At least the A-29 can get close enough to see where the friendlies are, and not bomb them”

In response to the SEALs’ request, the Navy committed Pentagon heresy by going backwards in airplane technology. Instead of jet engines, they found a propellor-driven plane worked better.

Years before, a Brazilian company called Embraer had built a plane specially made for the close-in aerial fighting that the dirty wars South American and African insurgencies required. The Navy immediately leased one of them for testing. (A later phase would have raised the number to four.) This is how Embraer’s EMB-314 Tucano became reborn as the A-29B Super Tucano.

The plane was refitted at the Navy’s test facility in Patuxent River, Maryland, and flown to an out-of-the-way airbase in Nevada so it could be seen how well this “Super T” could fight.

Around this time, someone decided to paint an iconic logo on the plane: a horse in solid black silhouette. It was a respectful nod to a legendary fighting unit in naval history. Back in Vietnam, the Navy’s VAL-4 squadron, the “Black Ponies,” saw heavy combat flying the turboprop OV-10 Bronco. It was a clear sign that these pilots saw their role as close combat with the enemy. And although it was an unofficial designation for the new A-29s, the Black Ponies were reborn.

Navy and Air Force pilots jumped at the chance to volunteer. Upon selection, pilots simply disappeared from their regular units. They started working with SEALs trained to call in airstrikes. This was a special operations mission, and this was a specops plane. On paper, they now worked for the Navy’s Irregular Warfare Office on Imminent Fury.

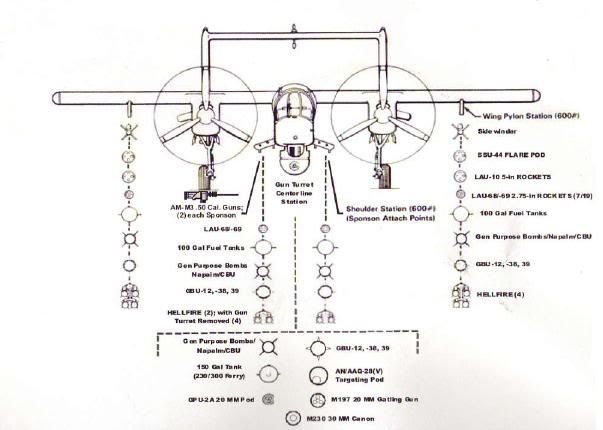

In Nevada, they shot 50-caliber machine guns mounted in the A-29’s wings. They dropped small laser-guided and GPS-guided bombs. They fired thousands of 2.75-inch rockets, some of which had laser-guidance upgrades. These were the types of weapons best suited to the war in Afghanistan. And for self-defense, the A-29 could even fire the same Sidewinder air-to-air missile used in their previous lives as jet pilots.

Multiple Imminent Fury test pilots, including Lt. Col. Mann, tell me that the plane was perfect for fighting guerrillas in Afghanistan. The commander in Afghanistan, Gen. Stanley McChrystal, wanted four of them flying in his skies immediately. But would the Pentagon really fight for this plane? Especially one that, technologically, ran in the complete opposite direction of its stealthy F-35?

CLOSER

In a way, the fight over the Super Tucano mirrored a little-known epoch from the Vietnam War. Back then, the Pentagon was busy purging the last of the Korean War-era planes from its fleet and investing heavily on Mach 2 fighters like the F-4 Phantom II, which it felt was needed for war with the Soviet Union.

But in 1971, while the Pentagon dithered over possible future wars with the Soviets, young Air Force pilots like Byron “Hook” Hukee were busy fighting a low, slow, dirty war in Southeast Asia. And to Hukee, “close air support” in war is simple.

“Close is 100 meters, not 1,000 meters,” he says.

Hukee flew the Korean War-era A-1 Skyraider, providing cover for helicopters trying to rescue downed American pilots in North Vietnam. And he says without equivocation that today’s bombs are just too big for supporting troops on the ground.

He often dropped the 250-pound Mark 81 bomb, nicknamed the Lady Finger for its slim shape and small size, within 100 meters of downed Americans fighting off North Vietnamese attackers. But in Afghanistan, the smallest bomb readily available was the 500-pound Mark 82, which can’t be safely used inside of nearly 600 meters from friendly ground troops.

Hukee also had a complement of even smaller weapons, such as the 100-pound M47 white phosphorous bomb that dated back to WWII, and he could also release small groups of a half-dozen cluster bombs on the enemy. Today, the smallest cluster bombs used in Afghanistan weigh about a 1,000 pounds and are loaded with more than 200 bomblets.

Hukee often had to fire rockets or shoot his four 20-mm cannons on a target, and because of his A-1’s slow speed he could adjust his point of aim and fire again before zooming overhead and turning around for another pass.

That’s impossible to do in a jet aircraft. Hukee says the F-4 jet pilots’ motto in Vietnam was “One Pass, Haul Ass,” meaning they’d typically drop 500-pound or larger bombs only once and then zoom off. But for Skyraiders, they’d come in low, slow, and pound the target—sometimes making a dozen or more passes before having to refuel.

More than four decades later, the tests at Naval Air Station Fallon, in western Nevada, showed that the Super T was the closest thing yet to the Skyraider’s capabilities. The A-29 was capable of flying and fighting from less than 1,000 feet above the ground. An armed Tucano has a loiter time of up to four hours, far better than fuel-hungry fighter jets which would usually stay overhead for as little as 20 minutes at a time before needing to refuel.

Typical fighter jets could only fly loose, three- or four-mile radius circles around a fight, but the Super T could remain as close as 500 meters to the target area. Perfect for responsive air strikes.

A-29 Super Tucano, rear cockpit. Photo: Senior Airman Ryan Callaghan/USAF

There was another technology battle as fundamental as the propeller-versus-jet-engine controversy, and that was about something the pilots call “pods.”

Short for “targeting pods,” these are removable electro-optical devices attached to the underside of an airplane that contain cameras and lasers to help with airstrikes. Looking at a plane like an F-16, one could easily mistake the pod for just another bomb. These pods allow pilots to more accurately drop bombs from high altitude, but the zoomed-in view of the ground the pilot sees is most often compared to looking at the horizon through a drinking straw.

The simple fact is that A-10 pilots didn’t need to rely on their pods in Afghanistan during daytime. They were flying low enough to verify friendly and enemy positions by just looking out their canopies—something pilots still jokingly refer to as “using the Mark-1 Mod 0 Eyeball.”

A-29 would have augmented the A-10 in this low-altitude daytime role, and it had a targeting pod for nighttime use to boot. This pod had an additional advantage of giving pilots confronted by heavy ground fire the possibility to engage from further away, if necessary.

But whenever possible, the A-29 would, like a true airborne killer, fly low and slow—able to support soldiers on the ground, as well as providing the type of backup checks that could prevent friendly fire accidents. This quality flies right in the face of the Air Force’s rationale behind using “fast mover” jets like the F-16 or the Navy’s F/A-18, which depend on what’s known as “the 8-minute rule.”

From the US Air Force and Navy’s perspective, it shouldn’t take a pilot more than eight minutes to reach troops fighting enemy combatants. It was a well-intentioned policy, but made a number of assumptions, chief of which was that responding to enemy attacks as fast as possible was the single best way to support troops. The Taliban quickly learned that US air power could arrive at a fight quickly, but taking advantage of that speed often ended up limiting the time those planes could spend overhead.

“Getting there in 8 minutes sounds accurate, but what you do then is a completely ****ing different thing”

Jets could race to a fight on afterburners, but be so low on gas by the time they arrived that they’d immediately have to refuel from an airborne tanker.

“Whenever air showed up, the Taliban would hunker down for a half hour or an hour, and after the aircraft left, they’d come right back and start shooting again,” says former US Army infantry captain Justin Quisenberry.

Quisenberry spent more than 30 months in Afghanistan during three combat tours, leading soldiers in numerous firefights. For him, air power was an indispensable component of Americans emerging on top from firefights with the Taliban, and to him loiter time was the decisive factor, not reaction speed.

The Super Tucano’s turboprop engine enabled it to fly as much as 12 times longer than jets like the F-16, which could’ve given Quisenberry almost non-stop air cover during his patrols. By 2006 that air power Quisenberry could draw from mainly came from just three airbases—at Kandahar, Bagram, and Camp Bastion—each with asphalt runways over 10,000 feet long.

Unlike the fast movers at those major bases, A-29s needed less than 4,000 feet of runway, which could be flattened dirt, gravel, or grass. This meant that Super Ts could be securely based at dozens of pre-existing small airfields all over Afghanistan—making up for their relatively slower top speed by being closer to where the troops needed them for greater stretches of time.

Listen to more on tech and forever war from Motherboard:

This would have been a revolutionary change, especially considering how the air war ran in the early days. Because Congress kept the defense money flowing after 9/11, the Air Force and Navy were never forced to consider how incredibly expensive their war plans were.

Moving B-52s and fuel tankers to the Middle East was about the only change made to save any time and money. Instead of flying 30-plus hour round trips (like it did right after 9/11) from Diego Garcia, the Air Force saved some time by flying out of Al Udeid Airbase in Qatar instead.

At first, the Air Force rotated all of their fighter jet squadrons in and out of Afghanistan every 90 days—that often included flying in and out all necessary tools and spare parts by cargo plane. Eventually those deployments stretched to four and even six months. But the flying service never had a dedicated lower-maintenance attack airplane like the Super Tucano, which it could just keep in the country until the war was over.

Similarly, the Navy rotated its Nimitz-class aircraft carrier in the northern Arabian Sea off Pakistan approximately every six months, though it could’ve just land-based squadrons of F/A-18s in Afghanistan like the Marines did.

Cruising up to 100 nautical miles from the port town of Karachi, the Navy’s carriers routinely launched F/A-18 Hornets (the Navy’s primary strike airplane) on 7-hour patrols over Pakistani airspace and into Afghanistan. Their typical profile: Enter Afghan airspace; refuel; spend 20 minutes “on station,” available in case ground troops needed them; refuel a second time; spend another 20 minutes on-station; refuel a third time before entering Pakistani airspace; and then fly back over that country and land on the carrier steaming offshore.

A few years after 9/11, those F/A-18s were going into Afghanistan loaded with just one laser-guided 500-pound bomb, one GPS-guided 500-pound bomb, and one AIM-9 air-to-air missile for self-defense. All of which a Super T can likewise carry on long-duration missions. The only difference is the Hornet’s internal 20-mm cannon, which is significantly larger than a Super T’s wing-mounted .50-cal machine guns. But an add-on 20-mm gun pod can be mounted underneath the A-29 fuselage, essentially matching the F/A-18’s typical weapons load and lethal capabilities.

Most of the time, those Hornets landed back on the carrier with all bombs still attached and guns unfired. The Hornet’s cost per flight hour? $25,000 to $30,000, according to official Navy figures. It’s estimated the F-35 costs anywhere between $31,900 to $38,400 per hour to fly. As for the Super T? $600 per hour, according to the Sierra Nevada Corporation, manufacturer of the A-29.

An A-29 Super Tucano flying (although not part of Imminent Fury). Photo: Senior Airman Ryan Callaghan/USAF

A look at a recent Navy aircraft carrier deployment provides some insight into the cost of doing business. When the USS Harry S. Truman returned to its homeport of Norfolk, Virginia, in 2014, the ship’s air wing had flown 2,902 combat sorties totaling 16,450 hours of flight time over Afghanistan. Low-balling the cost per flight hour of the Hornet flights at $25,000 per hour, this comes to roughly $411 million in taxpayer dollars spent on flight operations alone for the Truman’s deployment.

That amount of money could have bought more than enough of the $4 million Super Ts to cover all the “low-end” air support needs across Afghanistan. An Imminent Fury pilot who asked to remain anonymous adds that this would’ve lessened the wear and and tear on higher-end aircraft like the F-16s and F/A-18s, which had much of their services lives used up flying close-air support in Afghanistan.

And that was just one carrier deployment. Since 9/11, there have been dozens to the Pakistani coast.

When asked to quantify just how much taxpayer money has been spent on fuel and maintenance for even one carrier-based airplane over a decade of war, no government official will hazard even a qualified guess.

WHAT YOU DO WHEN YOU GET THERE

In testimony before Congress, admirals and generals continued to stress that speed was the most important factor in deciding which planes should be used in Afghanistan. But the “8-minute rule” standard breaks down when you talk to veteran pilots and air controllers.

“Getting there in 8 minutes sounds accurate, but what you do then is a completely ****ing different thing,” says an active-duty Army Special Forces air controller who also wished to not be named. “It might take 10 minutes to dial-in the fast mover,” the controller, who’s completed multiple combat tours, says, noting the time required to orient a jet pilot to the situation on the ground upon arrival.

He says dealing with unmanned aerial systems like the vaunted Predator and Reaper drones is even worse, taking twice as long to get dialed-in as the jets do. The reason is that drone pilots are only looking through their sensors and targeting pods.

“They can’t look out the canopy and see me, and then see the enemy,” the soldier explains. The pod, he says, “just doesn’t show you much of the ground, and so it can take a long time to make sure the pilot knows where I am, where the enemy is, and to make sure we’re both talking about the same thing. I won’t let him fire until I’m sure of both.”

“A lot depends on both the skill of the [air controller] and the skill of the pilot,” he adds. “It ain’t how fast you can get to the fight, it’s what you do when you get there that counts.”

Sadly, on June 9, 2014, more Americans died in a friendly fire incident that might not have happened with an A-29 overhead. A bomb dropped by a supersonic-capable B-1 Lancer bomber (built to pierce 1980s-era Soviet air defenses) flying high overhead killed five Americans and one Afghan. The soldiers who called in the airstrike thought the aircrew above could see the infrared strobes at the friendly position, but it turns out that kind of light can’t be detected at the altitude and ranges the B-1 was at. Not seeing the friendly strobes, the B-1 crew dropped a bomb on what it mistakenly thought were Taliban fighters.

Another high-altitude bomber dropping “precision” munitions on a target they couldn’t even see. Twelve-and-a-half years after the first high-profile friendly-fire bombing, American troops were still dying for lack of a better attack plane.

Even though Congress couldn’t see the value in having Americans flying the A-29 in Afghanistan, the Pentagon started to realize it might be a key part of their effort to turn the war back over to Afghan government forces.

While American units were fighting Taliban in 2010, America was leaving Iraq, and searching for opportunities to leave Afghanistan. Different procurement priorities and outright hostility from the Navy and Air Force left the A-29 vulnerable to political fights. Imminent Fury died in a Congressional committee in 2010.

Furthermore, one of the most vocal proponents of Imminent Fury, Gen. Stanley McChrystal, was forced to retire for his comments in a Rolling Stone interview about a week after Congress killed the A-29 program, thus removing the one advocate with enough political horsepower to possibly resurrect it. In the turmoil following McChrystal’s firing, Imminent Fury fell through the cracks and was largely forgotten about.

When that happened, the services didn’t put up a fight. One former Imminent Fury pilot jokes about how the Air Force didn’t want the Super T because “it couldn’t carry AMRAAM [missiles] or nukes, and the Navy didn’t want it because it didn’t have folding wings or a tailhook.”

Dominican Republic air force pilot and maintenance airman inspect an A-29 Super Tucano before a nighttime flight. Photo: Capt. Justin Brockhoff/USAF

Even with the demise of Imminent Fury, however, the Super T would not stay grounded for long, as Pentagon planners realized that it just might be the right plane for the Iraqis and Afghans to fly themselves.

The Pentagon decided the fledgling Afghan Air Force needed a “light support aircraft” to support their own ground troops after the Americans left. The Super Tucano had flown active combat missions against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, and proven itself off the test range. But Congress couldn’t decide whether to procure the A-29 or a competitor aircraft, a weaponized version of Beechcraft’s trainer airplane the company calls the AT-6B.

Even though the Air Force was cold about the idea of Americans buying and flying the A-29 in Afghanistan themselves, when it came to providing the Afghan Air Force with the same plane, the US Air Force was positively effusive, describing it as “indispensable to the operational and strategic success” of Afghanistan.

“The ‘cost’ of delay is more than a calculation of dollars and cents,” reads an Air Force memo in 2013. “In this case, further delay with resulting capability gaps could easily mean the loss of military and civilian lives.”

When asked if the Super Tucano could’ve helped American ground forces by filling the gap left by not having nearly enough A-10s, Pierre Sprey, the former DoD official, says, “Oh, beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

“At least the A-29 can get close enough to see where the friendlies are, and not bomb them. Close support is all about a constantly changing minute-to-minute firefight,” he tells me. “And if you’re not close enough to see where the puffs of smoke are from the enemy machine guns, you’re going to kill friendlies.”

The low-and-slow Super Tucano, manufactured in Brazil and completed in Florida, began arriving at a US Air Force base in September 2014, so that American pilots could train Afghans to fly them. Across the battlefields of Afghanistan, friendly Afghan forces are waiting for their promised air support, ready to begin learning to fly the planes themselves, and hoping to stave off a military catastrophe like the one that has struck Iraq.

Sierra Nevada is currently preparing to deliver even more Super Tucanos. The planes won’t be helping American soldiers, but they’ll likely play a role helping Afghans fight the Taliban. Meanwhile, the AT-6B has gone into production, too—to help the Iraqi Air Force’s fight against ISIS.

All Fronts is a series about technology and forever war. Follow along here.

This story was completed with support from the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

--

Topics: planes, all fronts, A-29B Super Tucano, Super Tucano, Super T, war, military, US Air Force, US navy, SEALs, Navy SEALs, Imminent Fury, machines, afghanistan, iraq, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, F-15, F-16, F/A-18, jets

Recommended

The US Air Force Watered Down the F-35 Fighter Jet to Avoid Embarrassment

The Japanese Space Agency Tested a Supersonic Plane With Less Sonic Boom

Russia Is Concerned About America's Far-Off Space Weapons

The Author of Our Best SF Military Novel Explains the Future of War

The UK's 'Dronecode' Is the Simplest Guide Yet for Drone Pilots

Moonshots for Planes: NASA's Got Out-There Concepts for Aviation Too

Comments 45

© 2015 Vice Media LLC

About Motherboard

For links see article source.....

Posted for fair use.....

http://motherboard.vice.com/read/low-and-slow

Motherboard

Newsletter

- All Fronts -

The WWII-Era Plane Giving the F-35 a Run for Its Money

Written by John Ismay, Adrian Bonenberger, and Damien Spleeters

September 18, 2015 // 08:15 AM EST

On December 5, 2001, an American B-52 flying tens of thousands of feet above the ground mistakenly dropped a 2,000-pound satellite-guided bomb on an Army Special Forces team in Afghanistan. The aircrew had been fed the wrong coordinates, but had the plane been flying as low and slow as older generations of attack planes did, the crew might’ve realized their error simply by looking down at the ground.

It was not long after the Twin Towers fell, and American soldiers were killed in Afghanistan by an American bomb dropped by an American plane. That this mistake happened illustrates just how poorly the air campaign in the United States’ longest war was executed, and how efforts ultimately failed to make things better by going after high-tech solutions that aren’t what they’re cracked up to be compared to the old tried and true technology.

That bomber was on a 30-plus hour round trip flight from the remote island of Diego Garcia, 900 miles south of India. The plane those Green Berets really needed, the low-and-slow flying A-10 Warthog, wasn’t available yet in Afghanistan. Famously rugged and even more famously lethal, the Warthog was the first American jet to actually land at the decrepit Bagram Airfield. Soon after the runway was repaired, many dozens of F-15, F-16, and F/A-18 fighter jets—wholly different creatures—came streaming in.

According to former Defense Department official Pierre Sprey, the US Air Force could have left those other jets out, had they sent three full squadrons of A-10s—72 planes total—to Afghanistan instead. But Sprey says the Air Force “never had more than 12 Warthogs in-country at any given time during the entire war.”

“The A-10 is the best ‘close attack’ plane ever made, period,” Sprey tells me. “But the Air Force hates that mission. They’ll do anything they can to kill that plane.” He says retiring the iconic A-10, a twin-engine attack jet with 30-mm cannons that hit with 14 times the kinetic energy of the 20-mm guns mounted on America’s current fleet of supersonic fighters, became an article of faith among high ranking Air Force officers, generations of whom had been raised to believe in the redemptive power of technological innovation.

They wanted something with more punch. More lethality. They soon found a plane built for exactly this purpose.

That mentality drove production of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the world’s first $1 trillion weapons system. Development of the F-35 was going on in the background throughout the Afghan War despite mountains of evidence that the stealthy jet would never be able to attack ground targets like the A-10 could. Far away from the fighting, the generals in Washington, DC supported the F-35 because they believed “more technology is always better.”

This same thinking drove the push for armed drones over Afghanistan too. But no matter their technological wizardry, remote-piloted hunter-killer aircraft like the Predator and Reaper were arguably even worse at helping ground troops than even the highest-tech manned jets.

So if the A-10 was never going to be around in enough numbers, what could be done? Only one group had enough distance from the Air Force and enough independent money to consider a viable alternative: buying a cheap, lightweight attack plane on their own. That was the Navy SEALs. A group of them met with the Secretary of the Navy in 2006 to tell him about the problems they faced with getting good enough air support.

Like other American combat troops in Afghanistan, the SEALs sometimes found that high-tech gear couldn’t reliably get the job done, or that cheaper, lower-tech solutions worked better. This is how the US military almost adopted the A-29 Super Tucano, a $4 million turboprop airplane reminiscent of WWII-era designs that troops wanted, commanders said was “urgently needed,” but Congress refused to buy.

RISE OF THE SUPER TUCANO

The Super Tucano was a throwback to a bygone era of aerial combat—a time when pilots looked through the blur of a propeller and pointed their nose at the enemy before pulling the trigger. A time before auto-pilot, guided missiles, and infrared gun “pods.” The A-29 was fast enough to get to a fight quickly and light enough to stay there in a low, slow orbit overhead the battle.

Philosophically, the Super Tucano occupies a sort of middle ground between the United States’ two main gunships. As a plane, the A-29 could reach altitudes over the Hindu Kush higher than the AH-64 Apache helicopter, and remain overhead for hours before refueling like the legendary AC-130 Spectre gunships.

But the Spectre only flew at night. By day, Super Tucano’s tight turning radius and low stall speed meant pilots could maintain constant visual contact with ground forces and instantly shift from surveillance and reconnaissance to attack. And after dark, an A-29 could use night vision and thermal sensors as sophisticated as those on any fighter jet.

“It’s a great plane,” says recently retired Air Force Lt. Col. Shamsher Mann, an F-16 pilot who has flown A-29s. “Pilots love it. It handles beautifully, sips gas, and can go anywhere. If you want to get into the fight and mix it up with the guys on the ground, the Super T is a great platform.”

Another former fighter pilot tells me that the Super Tucano provided the “low-end” air-to-ground attack capability the United States simply never had in Afghanistan—a capability the Pentagon’s F-35 could never hope to replicate.

Soon after 9/11, the pilot said, Army Special Forces famously rode horses into the Hindu Kush, but carried laptop computers and sophisticated targeting and communications gear with them as well. “Super Tucano is almost a mirror image of that in the air,” he said. “The low-tech combined with the high-tech.”

Now, five years after Congress killed the A-29 program, with the US Air Force considering a lower-tech replacement for the Warthog, the sad story of the Super Tucano feels more relevant than ever.

An A-29 Super Tucano spinning up. Photo: Senior Airman Ryan Callaghan/USAF

When former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld famously said of the Iraq invasion that “you go to war with the army you have” he also described how the United States started its fight in Afghanistan too.

Supersonic fighters, strategic bombers, and heavy attack helicopters developed to fight the Soviets succeeded in displacing the Taliban and knocking out Saddam Hussein, but proved incredibly cost-ineffective in the insurgencies that followed. Rather than take a step back to evaluate what was best suited for war in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Pentagon doubled down on big-ticket procurement items more suitable for large conventional wars than fighting insurgencies.

In America’s post-9/11 wars, however, the main combat role for tactical aircraft was something called “close air support,” where planes and helicopters are called in to wipe out enemy troops actively shooting at American ground forces. This enemy didn’t have tanks, planes, or helicopters. Sometimes it had motorcycles and pickup trucks. More often it was just people on foot, hiding in houses, in caves, or behind rocks or trees.

In Afghanistan, US troops didn't need airplanes that could evade detection from enemy radar; they needed planes that flew low enough for pilots to see the enemy eye-to-eye. They needed bombs dropped close enough to hurt them, bullets shot from the sky landing just out of arm's reach and into the enemy. They needed the Taliban dead.

When US troops were under fire, they needed aircraft that could stay through the fight, be accurate, and be deadly. Often times, troops needed ordnance “danger close”—generally inside of 500 meters from their own positions—and they’d rather have a pilot down low walk those shots in by eye than risk getting killed by an errant bomb dropped from a high-tech jet from 30,000 feet up, where a pilot can’t even see the target.

But for decades the arrow of progress had firmly pointed toward building and buying higher-tech planes. This would be an uphill battle pitting the worst-case scenario conventional war we might have to fight in the future against the insurgent war we were actually in now.

The Air Force insisted it would have to retire the Warthog fleet to pay for the world’s most expensive plane, the F-35. A plane which, incidentally, can’t fly or fight very well, so much so that the Air Force watered the fighter jet program down to save face. And the Air Force Chief of Staff recently begged off a comparison between the F-35 and A-10 as a “silly exercise,” probably because he knows just how badly the Joint Strike Fighter would fare head-to-head.

Political infighting like this led to poor air support in Afghanistan. And by 2006, a group of SEALs in Afghanistan were fed up with it. They asked the Secretary of the Navy personally for his help in getting a better plane overhead.

Not long after the SEALs’ request, the Secretary put together a small team and charged them with finding a better aircraft for this kind of war. Consensus quickly grew around a lightweight turboprop-driven plane. The team took possession of a couple old Vietnam-era OV-10 Broncos that last saw combat in Desert Storm, and started flying them. But they wanted something with more punch. More lethality. They soon found a plane built for exactly this purpose.

The classified Imminent Fury project was born.

“At least the A-29 can get close enough to see where the friendlies are, and not bomb them”

In response to the SEALs’ request, the Navy committed Pentagon heresy by going backwards in airplane technology. Instead of jet engines, they found a propellor-driven plane worked better.

Years before, a Brazilian company called Embraer had built a plane specially made for the close-in aerial fighting that the dirty wars South American and African insurgencies required. The Navy immediately leased one of them for testing. (A later phase would have raised the number to four.) This is how Embraer’s EMB-314 Tucano became reborn as the A-29B Super Tucano.

The plane was refitted at the Navy’s test facility in Patuxent River, Maryland, and flown to an out-of-the-way airbase in Nevada so it could be seen how well this “Super T” could fight.

Around this time, someone decided to paint an iconic logo on the plane: a horse in solid black silhouette. It was a respectful nod to a legendary fighting unit in naval history. Back in Vietnam, the Navy’s VAL-4 squadron, the “Black Ponies,” saw heavy combat flying the turboprop OV-10 Bronco. It was a clear sign that these pilots saw their role as close combat with the enemy. And although it was an unofficial designation for the new A-29s, the Black Ponies were reborn.

Navy and Air Force pilots jumped at the chance to volunteer. Upon selection, pilots simply disappeared from their regular units. They started working with SEALs trained to call in airstrikes. This was a special operations mission, and this was a specops plane. On paper, they now worked for the Navy’s Irregular Warfare Office on Imminent Fury.

In Nevada, they shot 50-caliber machine guns mounted in the A-29’s wings. They dropped small laser-guided and GPS-guided bombs. They fired thousands of 2.75-inch rockets, some of which had laser-guidance upgrades. These were the types of weapons best suited to the war in Afghanistan. And for self-defense, the A-29 could even fire the same Sidewinder air-to-air missile used in their previous lives as jet pilots.

Multiple Imminent Fury test pilots, including Lt. Col. Mann, tell me that the plane was perfect for fighting guerrillas in Afghanistan. The commander in Afghanistan, Gen. Stanley McChrystal, wanted four of them flying in his skies immediately. But would the Pentagon really fight for this plane? Especially one that, technologically, ran in the complete opposite direction of its stealthy F-35?

CLOSER

In a way, the fight over the Super Tucano mirrored a little-known epoch from the Vietnam War. Back then, the Pentagon was busy purging the last of the Korean War-era planes from its fleet and investing heavily on Mach 2 fighters like the F-4 Phantom II, which it felt was needed for war with the Soviet Union.

But in 1971, while the Pentagon dithered over possible future wars with the Soviets, young Air Force pilots like Byron “Hook” Hukee were busy fighting a low, slow, dirty war in Southeast Asia. And to Hukee, “close air support” in war is simple.

“Close is 100 meters, not 1,000 meters,” he says.

Hukee flew the Korean War-era A-1 Skyraider, providing cover for helicopters trying to rescue downed American pilots in North Vietnam. And he says without equivocation that today’s bombs are just too big for supporting troops on the ground.

He often dropped the 250-pound Mark 81 bomb, nicknamed the Lady Finger for its slim shape and small size, within 100 meters of downed Americans fighting off North Vietnamese attackers. But in Afghanistan, the smallest bomb readily available was the 500-pound Mark 82, which can’t be safely used inside of nearly 600 meters from friendly ground troops.

Hukee also had a complement of even smaller weapons, such as the 100-pound M47 white phosphorous bomb that dated back to WWII, and he could also release small groups of a half-dozen cluster bombs on the enemy. Today, the smallest cluster bombs used in Afghanistan weigh about a 1,000 pounds and are loaded with more than 200 bomblets.

Hukee often had to fire rockets or shoot his four 20-mm cannons on a target, and because of his A-1’s slow speed he could adjust his point of aim and fire again before zooming overhead and turning around for another pass.

That’s impossible to do in a jet aircraft. Hukee says the F-4 jet pilots’ motto in Vietnam was “One Pass, Haul Ass,” meaning they’d typically drop 500-pound or larger bombs only once and then zoom off. But for Skyraiders, they’d come in low, slow, and pound the target—sometimes making a dozen or more passes before having to refuel.

More than four decades later, the tests at Naval Air Station Fallon, in western Nevada, showed that the Super T was the closest thing yet to the Skyraider’s capabilities. The A-29 was capable of flying and fighting from less than 1,000 feet above the ground. An armed Tucano has a loiter time of up to four hours, far better than fuel-hungry fighter jets which would usually stay overhead for as little as 20 minutes at a time before needing to refuel.

Typical fighter jets could only fly loose, three- or four-mile radius circles around a fight, but the Super T could remain as close as 500 meters to the target area. Perfect for responsive air strikes.

A-29 Super Tucano, rear cockpit. Photo: Senior Airman Ryan Callaghan/USAF

There was another technology battle as fundamental as the propeller-versus-jet-engine controversy, and that was about something the pilots call “pods.”

Short for “targeting pods,” these are removable electro-optical devices attached to the underside of an airplane that contain cameras and lasers to help with airstrikes. Looking at a plane like an F-16, one could easily mistake the pod for just another bomb. These pods allow pilots to more accurately drop bombs from high altitude, but the zoomed-in view of the ground the pilot sees is most often compared to looking at the horizon through a drinking straw.

The simple fact is that A-10 pilots didn’t need to rely on their pods in Afghanistan during daytime. They were flying low enough to verify friendly and enemy positions by just looking out their canopies—something pilots still jokingly refer to as “using the Mark-1 Mod 0 Eyeball.”

A-29 would have augmented the A-10 in this low-altitude daytime role, and it had a targeting pod for nighttime use to boot. This pod had an additional advantage of giving pilots confronted by heavy ground fire the possibility to engage from further away, if necessary.

But whenever possible, the A-29 would, like a true airborne killer, fly low and slow—able to support soldiers on the ground, as well as providing the type of backup checks that could prevent friendly fire accidents. This quality flies right in the face of the Air Force’s rationale behind using “fast mover” jets like the F-16 or the Navy’s F/A-18, which depend on what’s known as “the 8-minute rule.”

From the US Air Force and Navy’s perspective, it shouldn’t take a pilot more than eight minutes to reach troops fighting enemy combatants. It was a well-intentioned policy, but made a number of assumptions, chief of which was that responding to enemy attacks as fast as possible was the single best way to support troops. The Taliban quickly learned that US air power could arrive at a fight quickly, but taking advantage of that speed often ended up limiting the time those planes could spend overhead.

“Getting there in 8 minutes sounds accurate, but what you do then is a completely ****ing different thing”

Jets could race to a fight on afterburners, but be so low on gas by the time they arrived that they’d immediately have to refuel from an airborne tanker.

“Whenever air showed up, the Taliban would hunker down for a half hour or an hour, and after the aircraft left, they’d come right back and start shooting again,” says former US Army infantry captain Justin Quisenberry.

Quisenberry spent more than 30 months in Afghanistan during three combat tours, leading soldiers in numerous firefights. For him, air power was an indispensable component of Americans emerging on top from firefights with the Taliban, and to him loiter time was the decisive factor, not reaction speed.

The Super Tucano’s turboprop engine enabled it to fly as much as 12 times longer than jets like the F-16, which could’ve given Quisenberry almost non-stop air cover during his patrols. By 2006 that air power Quisenberry could draw from mainly came from just three airbases—at Kandahar, Bagram, and Camp Bastion—each with asphalt runways over 10,000 feet long.

Unlike the fast movers at those major bases, A-29s needed less than 4,000 feet of runway, which could be flattened dirt, gravel, or grass. This meant that Super Ts could be securely based at dozens of pre-existing small airfields all over Afghanistan—making up for their relatively slower top speed by being closer to where the troops needed them for greater stretches of time.

Listen to more on tech and forever war from Motherboard:

This would have been a revolutionary change, especially considering how the air war ran in the early days. Because Congress kept the defense money flowing after 9/11, the Air Force and Navy were never forced to consider how incredibly expensive their war plans were.

Moving B-52s and fuel tankers to the Middle East was about the only change made to save any time and money. Instead of flying 30-plus hour round trips (like it did right after 9/11) from Diego Garcia, the Air Force saved some time by flying out of Al Udeid Airbase in Qatar instead.

At first, the Air Force rotated all of their fighter jet squadrons in and out of Afghanistan every 90 days—that often included flying in and out all necessary tools and spare parts by cargo plane. Eventually those deployments stretched to four and even six months. But the flying service never had a dedicated lower-maintenance attack airplane like the Super Tucano, which it could just keep in the country until the war was over.

Similarly, the Navy rotated its Nimitz-class aircraft carrier in the northern Arabian Sea off Pakistan approximately every six months, though it could’ve just land-based squadrons of F/A-18s in Afghanistan like the Marines did.

Cruising up to 100 nautical miles from the port town of Karachi, the Navy’s carriers routinely launched F/A-18 Hornets (the Navy’s primary strike airplane) on 7-hour patrols over Pakistani airspace and into Afghanistan. Their typical profile: Enter Afghan airspace; refuel; spend 20 minutes “on station,” available in case ground troops needed them; refuel a second time; spend another 20 minutes on-station; refuel a third time before entering Pakistani airspace; and then fly back over that country and land on the carrier steaming offshore.

A few years after 9/11, those F/A-18s were going into Afghanistan loaded with just one laser-guided 500-pound bomb, one GPS-guided 500-pound bomb, and one AIM-9 air-to-air missile for self-defense. All of which a Super T can likewise carry on long-duration missions. The only difference is the Hornet’s internal 20-mm cannon, which is significantly larger than a Super T’s wing-mounted .50-cal machine guns. But an add-on 20-mm gun pod can be mounted underneath the A-29 fuselage, essentially matching the F/A-18’s typical weapons load and lethal capabilities.

Most of the time, those Hornets landed back on the carrier with all bombs still attached and guns unfired. The Hornet’s cost per flight hour? $25,000 to $30,000, according to official Navy figures. It’s estimated the F-35 costs anywhere between $31,900 to $38,400 per hour to fly. As for the Super T? $600 per hour, according to the Sierra Nevada Corporation, manufacturer of the A-29.

An A-29 Super Tucano flying (although not part of Imminent Fury). Photo: Senior Airman Ryan Callaghan/USAF

A look at a recent Navy aircraft carrier deployment provides some insight into the cost of doing business. When the USS Harry S. Truman returned to its homeport of Norfolk, Virginia, in 2014, the ship’s air wing had flown 2,902 combat sorties totaling 16,450 hours of flight time over Afghanistan. Low-balling the cost per flight hour of the Hornet flights at $25,000 per hour, this comes to roughly $411 million in taxpayer dollars spent on flight operations alone for the Truman’s deployment.

That amount of money could have bought more than enough of the $4 million Super Ts to cover all the “low-end” air support needs across Afghanistan. An Imminent Fury pilot who asked to remain anonymous adds that this would’ve lessened the wear and and tear on higher-end aircraft like the F-16s and F/A-18s, which had much of their services lives used up flying close-air support in Afghanistan.

And that was just one carrier deployment. Since 9/11, there have been dozens to the Pakistani coast.

When asked to quantify just how much taxpayer money has been spent on fuel and maintenance for even one carrier-based airplane over a decade of war, no government official will hazard even a qualified guess.

WHAT YOU DO WHEN YOU GET THERE

In testimony before Congress, admirals and generals continued to stress that speed was the most important factor in deciding which planes should be used in Afghanistan. But the “8-minute rule” standard breaks down when you talk to veteran pilots and air controllers.

“Getting there in 8 minutes sounds accurate, but what you do then is a completely ****ing different thing,” says an active-duty Army Special Forces air controller who also wished to not be named. “It might take 10 minutes to dial-in the fast mover,” the controller, who’s completed multiple combat tours, says, noting the time required to orient a jet pilot to the situation on the ground upon arrival.

He says dealing with unmanned aerial systems like the vaunted Predator and Reaper drones is even worse, taking twice as long to get dialed-in as the jets do. The reason is that drone pilots are only looking through their sensors and targeting pods.

“They can’t look out the canopy and see me, and then see the enemy,” the soldier explains. The pod, he says, “just doesn’t show you much of the ground, and so it can take a long time to make sure the pilot knows where I am, where the enemy is, and to make sure we’re both talking about the same thing. I won’t let him fire until I’m sure of both.”

“A lot depends on both the skill of the [air controller] and the skill of the pilot,” he adds. “It ain’t how fast you can get to the fight, it’s what you do when you get there that counts.”

Sadly, on June 9, 2014, more Americans died in a friendly fire incident that might not have happened with an A-29 overhead. A bomb dropped by a supersonic-capable B-1 Lancer bomber (built to pierce 1980s-era Soviet air defenses) flying high overhead killed five Americans and one Afghan. The soldiers who called in the airstrike thought the aircrew above could see the infrared strobes at the friendly position, but it turns out that kind of light can’t be detected at the altitude and ranges the B-1 was at. Not seeing the friendly strobes, the B-1 crew dropped a bomb on what it mistakenly thought were Taliban fighters.

Another high-altitude bomber dropping “precision” munitions on a target they couldn’t even see. Twelve-and-a-half years after the first high-profile friendly-fire bombing, American troops were still dying for lack of a better attack plane.

Even though Congress couldn’t see the value in having Americans flying the A-29 in Afghanistan, the Pentagon started to realize it might be a key part of their effort to turn the war back over to Afghan government forces.

While American units were fighting Taliban in 2010, America was leaving Iraq, and searching for opportunities to leave Afghanistan. Different procurement priorities and outright hostility from the Navy and Air Force left the A-29 vulnerable to political fights. Imminent Fury died in a Congressional committee in 2010.

Furthermore, one of the most vocal proponents of Imminent Fury, Gen. Stanley McChrystal, was forced to retire for his comments in a Rolling Stone interview about a week after Congress killed the A-29 program, thus removing the one advocate with enough political horsepower to possibly resurrect it. In the turmoil following McChrystal’s firing, Imminent Fury fell through the cracks and was largely forgotten about.

When that happened, the services didn’t put up a fight. One former Imminent Fury pilot jokes about how the Air Force didn’t want the Super T because “it couldn’t carry AMRAAM [missiles] or nukes, and the Navy didn’t want it because it didn’t have folding wings or a tailhook.”

Dominican Republic air force pilot and maintenance airman inspect an A-29 Super Tucano before a nighttime flight. Photo: Capt. Justin Brockhoff/USAF

Even with the demise of Imminent Fury, however, the Super T would not stay grounded for long, as Pentagon planners realized that it just might be the right plane for the Iraqis and Afghans to fly themselves.

The Pentagon decided the fledgling Afghan Air Force needed a “light support aircraft” to support their own ground troops after the Americans left. The Super Tucano had flown active combat missions against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, and proven itself off the test range. But Congress couldn’t decide whether to procure the A-29 or a competitor aircraft, a weaponized version of Beechcraft’s trainer airplane the company calls the AT-6B.

Even though the Air Force was cold about the idea of Americans buying and flying the A-29 in Afghanistan themselves, when it came to providing the Afghan Air Force with the same plane, the US Air Force was positively effusive, describing it as “indispensable to the operational and strategic success” of Afghanistan.

“The ‘cost’ of delay is more than a calculation of dollars and cents,” reads an Air Force memo in 2013. “In this case, further delay with resulting capability gaps could easily mean the loss of military and civilian lives.”

When asked if the Super Tucano could’ve helped American ground forces by filling the gap left by not having nearly enough A-10s, Pierre Sprey, the former DoD official, says, “Oh, beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

“At least the A-29 can get close enough to see where the friendlies are, and not bomb them. Close support is all about a constantly changing minute-to-minute firefight,” he tells me. “And if you’re not close enough to see where the puffs of smoke are from the enemy machine guns, you’re going to kill friendlies.”

The low-and-slow Super Tucano, manufactured in Brazil and completed in Florida, began arriving at a US Air Force base in September 2014, so that American pilots could train Afghans to fly them. Across the battlefields of Afghanistan, friendly Afghan forces are waiting for their promised air support, ready to begin learning to fly the planes themselves, and hoping to stave off a military catastrophe like the one that has struck Iraq.

Sierra Nevada is currently preparing to deliver even more Super Tucanos. The planes won’t be helping American soldiers, but they’ll likely play a role helping Afghans fight the Taliban. Meanwhile, the AT-6B has gone into production, too—to help the Iraqi Air Force’s fight against ISIS.

All Fronts is a series about technology and forever war. Follow along here.

This story was completed with support from the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

--

Topics: planes, all fronts, A-29B Super Tucano, Super Tucano, Super T, war, military, US Air Force, US navy, SEALs, Navy SEALs, Imminent Fury, machines, afghanistan, iraq, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, F-15, F-16, F/A-18, jets

Recommended

The US Air Force Watered Down the F-35 Fighter Jet to Avoid Embarrassment

The Japanese Space Agency Tested a Supersonic Plane With Less Sonic Boom

Russia Is Concerned About America's Far-Off Space Weapons

The Author of Our Best SF Military Novel Explains the Future of War

The UK's 'Dronecode' Is the Simplest Guide Yet for Drone Pilots

Moonshots for Planes: NASA's Got Out-There Concepts for Aviation Too

Comments 45

© 2015 Vice Media LLC

About Motherboard

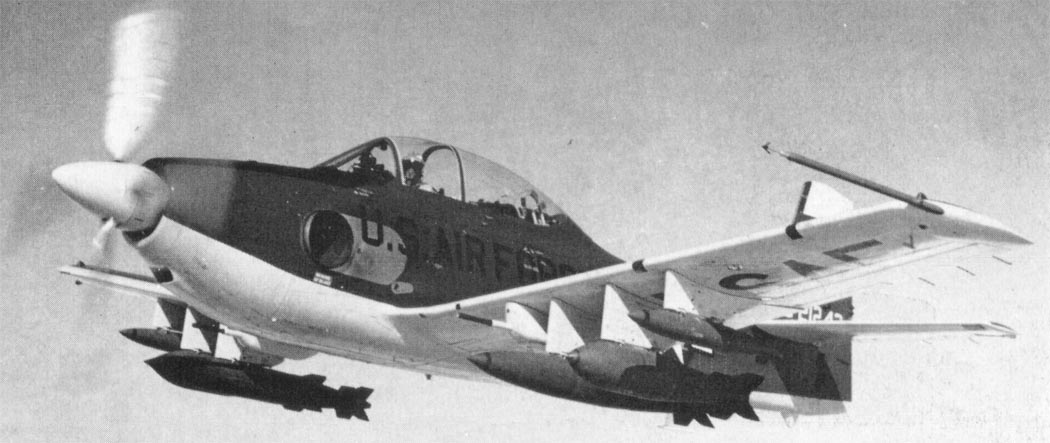

(Hard to see, but the aircraft armament placard has written on it; 30MM--the black square on the side behind the cockpit) Forest cammo seems fitting.

(Hard to see, but the aircraft armament placard has written on it; 30MM--the black square on the side behind the cockpit) Forest cammo seems fitting.