You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

ALERT The Winds of War Blow in Korea and The Far East

- Thread starter northern watch

- Start date

jward

passin' thru

Joseph Dempsey

@JosephHDempsey

North Korea confirms third round of cruise missile launches within a week.

Notable indicating a move toward Hwasal-2 training rather than testing.

View: https://twitter.com/JosephHDempsey/status/1752476508667388189?s=20

@JosephHDempsey

North Korea confirms third round of cruise missile launches within a week.

Notable indicating a move toward Hwasal-2 training rather than testing.

View: https://twitter.com/JosephHDempsey/status/1752476508667388189?s=20

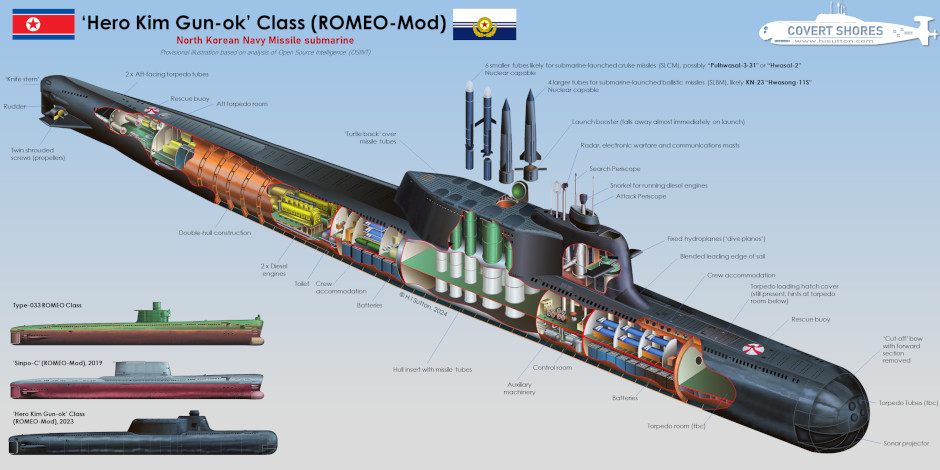

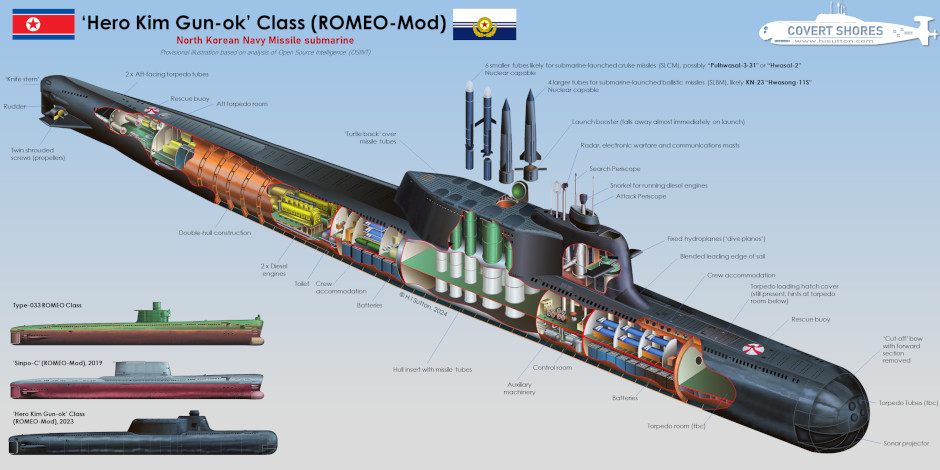

My concern is whether or not they can launch them out of the torpedo tubes on the 20 Romeo SSKs they still have?......

Posted for fair use.......

Friday

February 2, 2024

![A Hwasal-2 cruise missile flies at low altitude on the western coast of North Korea on Tuesday morning in this photo released by Pyongyang's state-controlled Korean Central News Agency on Wednesday. [YONHAP] A Hwasal-2 cruise missile flies at low altitude on the western coast of North Korea on Tuesday morning in this photo released by Pyongyang's state-controlled Korean Central News Agency on Wednesday. [YONHAP]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/02/02/96851ef2-c1b6-4f90-8608-457f6d809994.jpg)

A Hwasal-2 cruise missile flies at low altitude on the western coast of North Korea on Tuesday morning in this photo released by Pyongyang's state-controlled Korean Central News Agency on Wednesday. [YONHAP]

North Korea fired several cruise missiles from its western coast on Friday morning, according to the South Korean military.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) told reporters in a text message that it detected multiple cruise missiles being fired around 11 a.m., but did not specify the number of missiles.

The launches on Friday mark the fourth cruise missile salvo fired by the North since the beginning of the year.

On Tuesday, the North conducted what it later said was a test of the Hwasal-2 cruise missile, which also took place off its western coast.

The North test-fired newly developed Pulhwasal-3-31 cruise missiles for the first time from its western coast on Jan. 24. The regime said it also fired Pulhwasal-3-31 cruise missiles from an unspecified underwater launch platform off its eastern coast on Sunday.

Hwasal in Korean means “arrow,” while Pulhwasal means “flaming arrow.”

In its message, the JCS said that the South Korean military “is closely coordinating with the United States to monitor additional signs of North Korea’s provocations.”

While the North is formally barred from carrying out tests of ballistic missile technology under resolutions passed by the United Nations Security Council, no such restrictions apply to its cruise missile program.

However, experts say the North’s cruise missiles still pose a risk to South Korea and Japan because they are harder to detect by radar and intercept.

It remains unclear why the North has ramped up testing of its latest line of cruise missiles, but South Korean military officials have told reporters on condition of anonymity that the quick succession of launches is likely aimed at perfecting the new weapons system in a short period.

BY MICHAEL LEE [lee.junhyuk@joongang.co.kr]

Posted for fair use.......

North fires several cruise missiles from western coast: JCS

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) told reporters in a text message that it detected multiple cruise missiles being fired around 11 a.m., but did not specify the number of missiles.

koreajoongangdaily.joins.com

Friday

February 2, 2024

North fires several cruise missiles from western coast: JCS

![A Hwasal-2 cruise missile flies at low altitude on the western coast of North Korea on Tuesday morning in this photo released by Pyongyang's state-controlled Korean Central News Agency on Wednesday. [YONHAP] A Hwasal-2 cruise missile flies at low altitude on the western coast of North Korea on Tuesday morning in this photo released by Pyongyang's state-controlled Korean Central News Agency on Wednesday. [YONHAP]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/02/02/96851ef2-c1b6-4f90-8608-457f6d809994.jpg)

A Hwasal-2 cruise missile flies at low altitude on the western coast of North Korea on Tuesday morning in this photo released by Pyongyang's state-controlled Korean Central News Agency on Wednesday. [YONHAP]

North Korea fired several cruise missiles from its western coast on Friday morning, according to the South Korean military.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) told reporters in a text message that it detected multiple cruise missiles being fired around 11 a.m., but did not specify the number of missiles.

The launches on Friday mark the fourth cruise missile salvo fired by the North since the beginning of the year.

On Tuesday, the North conducted what it later said was a test of the Hwasal-2 cruise missile, which also took place off its western coast.

The North test-fired newly developed Pulhwasal-3-31 cruise missiles for the first time from its western coast on Jan. 24. The regime said it also fired Pulhwasal-3-31 cruise missiles from an unspecified underwater launch platform off its eastern coast on Sunday.

Hwasal in Korean means “arrow,” while Pulhwasal means “flaming arrow.”

In its message, the JCS said that the South Korean military “is closely coordinating with the United States to monitor additional signs of North Korea’s provocations.”

Related Article

Yoon warns against North meddling in April's general elections

South Korean envoy warns North that provocations strengthen trilateral resolve

North says it conducted Hwasal-2 cruise missile drill

North says Kim oversaw test of 'sub-launched' cruise missiles

While the North is formally barred from carrying out tests of ballistic missile technology under resolutions passed by the United Nations Security Council, no such restrictions apply to its cruise missile program.

However, experts say the North’s cruise missiles still pose a risk to South Korea and Japan because they are harder to detect by radar and intercept.

It remains unclear why the North has ramped up testing of its latest line of cruise missiles, but South Korean military officials have told reporters on condition of anonymity that the quick succession of launches is likely aimed at perfecting the new weapons system in a short period.

BY MICHAEL LEE [lee.junhyuk@joongang.co.kr]

northern watch

TB Fanatic

jward

passin' thru

Paul Sperry

@paulsperry_

DEVELOPING: The Taliban has asked to join China's Belt & Road Initiative and has already signed contracts with China allowing the Communist regime to drill for oil and gas in Afghanistan and to mine lithium and copper in the mineral-rich country, a new Pentagon IG report reveals.

10:40 PM · Feb 2, 2024

3,694

Views

jward

passin' thru

The US Is Raising Tensions With North Korea

In January, two veteran Korea watchers — Robert Carlin and Siegfried Hecker — published a provocative short piece that argues that, “like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war.” Carlin and Hecker contend that in the wake of the Hanoi Summit’s failure in 2019, the Kim regime abandoned North Korea’s thirty-year goal of normalizing relations with the United States. Citing recent shifts in government rhetoric and policy, they warn that “the situation may have reached the point that we must seriously consider a worst case” — meaning North Korean military action backed up by nuclear weapons.

Alarmist claims about North Korea are common, but the piece raised eyebrows precisely because the two analysts are not known for them. Both are widely respected and eminently credentialed: Carlin is the former head of the Northeast Asia Division in the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the State Department, and Hecker is a former director of Los Alamos who has actually visited North Korean nuclear facilities.

Their argument was provocative enough that it even garnered coverage in the mainstream press, with NBC News asking in a headline: “Is Kim Jong Un preparing North Korea for war?” While the Korea-watcher community has been skeptical, the article does raise some questions: what would lead two dovish analysts to warn of a strategic shift by North Korea? Is it possible the Kim government really has decided to go to war?

The news from North Korea is bad and getting worse, but it does not add up to incontrovertible evidence of a pro-war strategic shift. That said, I think Carlin and Hecker are correct to draw attention to North Korea’s changing approach to the United States.

Something is happening. Where once better relations were held out as a distant possibility, the Kim government now seems to be foreclosing on that option — and replacing it with closer coordination with US adversaries. But to understand why the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) may be making that change, we have to move beyond analyzing its relationship with the United States per se and instead explore the ongoing militarization of the Pacific, the impact of right-wing governance in South Korea, the negative consequences of US sanctions, and the Biden administration’s commitment to what is euphemistically called “great power competition.”

One Country’s Exercise Is Another Country’s Provocation

The failed Hanoi Summit has certainly played a major role in North Korea’s shifting pose. Faced with an opportunity to limit the North Korean nuclear arsenal, the Trump administration instead demanded total disarmament — and walked away with nothing. US commentators praised Donald Trump for rejecting a bad deal, but as nuclear weapons expert Jeffrey Lewis wrote at the time, the deal was probably the best the United States could have gotten.

Kim Jong Un no doubt felt he had been taken for a ride, especially given the propaganda shifts necessary to undertake negotiations in 2018 and 2019. When the summit fell apart, North Korea responded by making 2019 a record year for missile tests. In 2022, it more than doubled that record.

But while Hanoi has been a key factor in North Korea’s increasingly antagonistic posture, subsequent events have been just as important. For one thing, the Biden administration simply has not made North Korea a diplomatic priority. The administration often stresses its willingness to talk “without preconditions,” but it has done little if anything to entice North Korea to the negotiating table.

The DPRK’s reluctance to talk is frustrating, but as a fellow analyst recently mentioned, conditions may be exactly what the Kim regime needs to hear from the US. If you want to avoid an embarrassing repeat of Hanoi, it makes sense to want to see concrete goals and ground rules for talks ahead of time.

Relations are stuck in a vicious cycle. The administration declares its willingness to talk but is unwilling to make concessions to incentivize the North Koreans to negotiate; North Korea views US messaging skeptically and refuses to talk. The US responds by beefing up “deterrence,” stressing that while it remains open to negotiations, an expanded military presence in the region is necessary to keep Kim Jong Un in check. (Perhaps more important, it also fits with the overriding US goal of countering China.) North Korea then sees these deployments as evidence of nefarious intentions and views the next US statement with even greater suspicion. The cycle continues.

The point is that military assets will always speak louder than words — and the Biden administration’s approach to the Korean peninsula relies heavily on military assets. In July, it broke forty years of precedent by sending a nuclear-armed submarine to make a port call in Busan, South Korea. President Yoon Suk-yeol boarded the sub and declared publicly that any “nuclear provocation” from the North would result in “the end of the regime.”

Biden has also pushed for near constant and often expanded military exercises to shore up deterrence. To cite examples from just the past year, the US–South Korean field exercises held in March 2023 were the largest in five years, and the live-fire drills that followed in May were said to be the biggest ever.

Large-scale annual drills were also held in August, but amid these regular exercises there have been innumerable other drills between the US and Japan, the US and South Korea, and even trilateral exercises between all three. Is it any surprise that a country surrounded by coordinating adversaries projecting military power may have given up on the prospect of détente?

Trilateralism and Empires Old and New

We know that North Korea already regards bilateral exercises as provocative, so one can imagine what the Kim regime thinks of growing trilateral security cooperation. In August, President Biden hosted the leaders of South Korea and Japan at a high-profile Camp David summit. In a joint statement, the three parties declared “a new era of trilateral partnership” and committed to “raise our shared ambition to a new horizon, across domains and across the Indo-Pacific and beyond.”

Among other things, this partnership will include “annual, named, multi-domain trilateral exercises on a regular basis to enhance our coordinated capabilities and cooperation.” Increased trilateralism has long been the dream of hawkish US analysts, who support a far more extensive military presence in Northeast Asia. Biden — in the name of deterrence and competition — has helped make this expansion a reality.

Trilateralism is sold to policymakers and the public as a mechanism to deter North Korea, and it is true that many of its facets are directed at the Kim regime. It is likely, though, that for the United States, trilateral cooperation has more to do with China than the fiery but more or less contained DPRK. Checking Chinese power is the overarching goal of US strategy and shoring up alliances in the Pacific is a logical step in establishing an anti-China bloc.

In that sense, trilateralism is similar to the AUKUS deal announced in 2021. That agreement was ostensibly about providing Australia with nuclear-powered submarines, but it only really makes sense as a way to expand the capabilities of US allies in the Pacific to counter the Chinese military.

A true anti-China bloc will not be built overnight. Indeed, many Asian countries retain an ambivalent stance on China, in part because of the country’s sheer economic power. Even the Biden administration is cagey about the topic, stressing that it seeks competition rather than outright conflict.

But from the administration’s standpoint, deterrence — the bedrock of “managed competition” — requires long-term planning, so it must act now if opportunities arise that could lead to closer coordination against China in the future. The election of Yoon Suk-yeol in South Korea was one such opportunity.

The joint statement includes a note of praise from President Biden, who commends Japanese prime minister Kishida Fumio and South Korean president Yoon “for their courageous leadership in transforming relations between Japan and the ROK [Republic of Korea Army].” The note parallels comparable statements from US-based analysts, who have treated Yoon as a visionary willing to buck domestic opinion to secure the region’s long-term security. Trilateralism is indeed controversial in South Korea, although analysts typically do not state the reasons — the living memory of Japanese occupation and continued imperial apologia in Japan.

Also unmentioned is the obvious reason Yoon had no problem making his “courageous” decision: South Korean conservatives have a very positive view of the Japanese right, an orientation that stretches back to collaboration during the 1910–1945 occupation. It continues today. In March, Yoon announced a settlement to the ongoing question of monetary compensation for Korean victims of wartime forced labor, about 1,800 of whom are still living. Opposing the rulings of South Korean courts (which have found Japanese companies liable) and the wishes of the victims themselves, Yoon’s proposal will instead use money from South Korean corporations to pay out compensation to claimants. Japan, the former colonial occupier, is not required to contribute.

President Biden praised the deal for inaugurating “a groundbreaking new chapter” in relations between the two countries. The growth of American power in the Pacific is being accomplished by sweeping the history of Japanese colonialism under the rug.

jward

passin' thru

Our Man in Seoul

Conservative South Korean president Yoon’s narrow victory in 2022 enabled many of the policy changes mentioned above. Earlier in his presidency, Yoon made a not-so-subtle threat to explore the possibility of a South Korean nuclear arsenal. His comments garnered the attention of the Biden administration (probably on purpose), which created the Nuclear Consultative Group to bring South Korea into deterrence planning and tamp down talk of proliferation. Yoon’s comments were likely also what pushed the US to start sending nuclear-armed subs to the peninsula, as a show of its commitment to “extended deterrence.”

More broadly, conservatism in South Korea is defined by a hawkish stance toward the North, so Yoon’s foreign policy aligns with longstanding US preferences for pressure (sanctions), deterrence (military power), and denuclearization (up-front disarmament). He is a reliable partner for the Biden administration, in other words, because he already agrees with what it wants to do.

Domestically, Yoon’s militarist impulse has led his administration to restart nationwide civil defense drills and organize the first military parade in downtown Seoul in a decade. The last such parade was held during the reign of disgraced conservative president Park Geun-hye, who was later deposed in the Candlelight Revolution of 2016–17.

Coverage of Yoon in the United States is reminiscent of the fawning treatment given to former Japanese prime minister Abe Shinzo, who was depicted as a gentle statesman despite being a right-wing nationalist. (Steve Bannon once called him “Trump before Trump.”) Yoon has spent much of his presidency in an extreme anti–communist mode, trying to tie the domestic opposition to the DPRK. In an August speech commemorating Korea’s liberation from the Japanese Empire, Yoon warned of “anti-state forces” working to harm South Korea from within. “The forces of communist totalitarianism,” Yoon declared, “have always disguised themselves as democracy activists, human rights advocates, or progressive activists while engaging in despicable and unethical tactics and false propaganda.”

The statement is shocking in its own right, but it is particularly offensive in South Korea, where activists spent decades fighting for democracy while being tarred by conservatives as North Korean operatives. Some of those activists — like former president Moon Jae-in — are now senior members of the opposition party.

Yoon’s demagoguery matters because, while South Korean democracy is healthier than that of its alliance partner, it could hardly be described as stable. The situation is volatile enough that writer Tammy Kim warned of democratic erosion in a September piece for the New Yorker, citing Yoon’s threats to “protections for women, the right to associate and organize, and, most strikingly, freedom of the press.”

More ominous, in early January South Korean opposition leader Lee Jae-myung was stabbed in the neck during an appearance in Busan. Lee was rushed to surgery and luckily survived. The perpetrator, a sixty-seven-year-old realtor, told police that he stabbed Lee to prevent him from becoming president. The would-be assassin apparently believed that “pro-North Korean forces” in the judiciary were delaying attempts to hold Lee accountable, and that killing him would prevent a left-wing takeover. Yoon has of course denounced the stabbing, but one wonders whether his right-wing bully pulpit has played a role in stirring up anti-communist extremism.

The Emerging Pariah Bloc

In October, US officials revealed that North Korea shipped more than one thousand containers of equipment and munitions to Russia for use in its war against Ukraine. National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby, lately known as the administration’s chief defender of its Israel policy, stated at the time, “We condemn the DPRK for providing Russia with this military equipment, which will be used to attack Ukrainian cities, kill Ukrainian civilians, and further Russia’s illegitimate war.”

Kirby expressed concern that arms transfers could eventually go both ways, with Russia providing technology to North Korea that it could not normally receive under international sanctions. More details emerged in January when analysts found strong evidence that Russia had used the Hwasong-11, a North Korean ballistic missile, in at least two attacks against Ukraine.

The news caps a year in which Kim Jong Un used a number of public appearances to show off the North Korean arms industry. Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu visited Pyongyang in July, where he viewed two drone designs and an intercontinental ballistic missile. It was, perhaps significantly, the first state visit since North Korea closed its borders in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shoigu later told journalists that the two countries were considering a joint military exercise. And of course Vladimir Putin hosted Kim Jong Un at a September summit, where the two toured a Russian factory that constructs fighter jets.

North Korean support for Russia’s war in Ukraine has been rightly met with shock and disgust, but it should not be surprising — least of all to the US government. The broad sanctions levied against Russia for its illegal invasion were bound to push it closer to other US adversaries, which share little in common except their status as economic pariahs. North Korea has been under extreme sanctions for years (especially since 2016 and 2017), and while smuggling and hacking soften the blow, they’re hardly a substitute for large-scale arms deals. In this case, the Kim government probably saw an opening — the Russian need for materiel to prosecute the war — and jumped on it. The benefits for North Korea are political as well as economic: not only do arms deals bring in much needed energy, fuel, and cash; they also throw a monkey wrench into the UN sanctions regime, which Russia until recently supported.

Tellingly, Kirby confirmed in January that Russia is looking to buy additional missiles from Iran, which is subject to “arguably the most extensive and comprehensive set of sanctions that the United States maintains on any country,” according to the Congressional Research Service. Sanctions may have economically isolated US adversaries from countries within its own orbit, but they have also drawn those adversaries closer together. With the headlong plunge into great power competition, backed up by the pursuit of military primacy, sanctioned countries’ convergence into a more solidified opposition seems likely to continue.

A Hostile Environment

To return to our starting point, consider the environment facing North Korea: It feels burned by a United States that did not accept the deal on offer at Hanoi. It sees a constant display of military power in its backyard by three countries that are deepening their cooperation. Where once trilateralism was a mere threat, now it functionally exists — thanks to US strategy against China and the election of a hawkish South Korean president. Russia, a friendly neighbor and a fellow target of sanctions, is in need of weapons and ammunition.

The DPRK is seizing the opportunity, knowing full well it will raise the ire of the United States. And why not? The American position since Hanoi has been perfectly — which is to say militarily — clear.

Some might object that this analysis focuses too intently on choices made by the United States; they might even say it erases North Korea’s “agency.” But while the autocratic Kim government does bear responsibility for the state of tensions, we cannot ignore the asymmetry between a poor, besieged state and a superpower capable of changing global security conditions on a whim.

Countries make their own decisions, you might say, but they do not make them as they please. They do not make them under self-selected circumstances but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted by the superpowers’ actions of the past — including the very recent past. We may find North Korea’s choices to be appalling, even dangerous, but they are not irrational. The Kim government has assessed the security conditions, which are overwhelmingly set by the world hegemon, and placed its bets accordingly.

North Korea’s decision to turn further away from the United States and toward its adversaries probably does increase the risk of war. But that is not to say the situation has reached a point of no return. The problem is that pulling back will require more than just a dramatic change in the US-DPRK relationship, which was already unlikely. That relationship is now inextricably bound up with both competition against China and tensions with Russia that stem from US support for Ukraine. These are all interlocking challenges, in other words, and the situation with North Korea is only one example of how great power competition is exacerbating tensions in regions that were already powder kegs.

The stakes are high: behind all these interrelated crises lies the potential for nuclear war. North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, still unrestrained, continues to advance. The last bilateral treaty limiting US and Russian nuclear weapons expires in 2026. The United States is spending $1.7 trillion to modernize its entire nuclear arsenal over the next thirty years. Russia recently deployed tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus. China is undergoing a major expansion of its once modest nuclear arsenal. We’ve got to kill great power competition before it kills us.

The US Is Raising Tensions With North Korea

Hummm......

Posted for fair use......

in News, World

In his most intensive drive for power over the Korean peninsula since his father’s death more than 12 years ago, North Korea’s Kim Jong Un is mounting a blitzkrieg of weapons tests and rhetoric. His goal: to convince both his own people and his enemies that he’ll risk a second Korean War to reunite North and South Korea under one-man rule.

Buoyed by his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Kim is shipping artillery shells and missiles for Russian forces bogged down in Ukraine while spreading fears of a grand plan to take over South Korea. The dream is to fulfill the vision of his grandfather, regime founder Kim Il Sung, who tried and failed to conquer the South in the first Korean War.

Kim’s big talk, his decision to give up all pretense of dealing with South Korea, above all his dedication to a nuclear program capable of inflicting mass death from Northeast Asia to the U.S., has experts forecasting more and bigger weapons tests—on top of unremitting threats.

“It looks like Kim Jong Un is talking about absorption by conquest,” said Nicholas Eberstadt, long-time researcher at the American Enterprise Institute. “What’s changed since last year? We know that North Korea is preparing for nuclear war on the Korean peninsula.”

Eberstadt, talking to The Daily Beast, qualified that bold assertion by noting that South Korea, with a strong economy and a well-equipped military establishment, supported by its American ally, is far more powerful than the impoverished North Korea, whose 1.2 million troops are underfed, ill-equipped, and often used as slave labor on farms and construction projects.

“Do they really think they are ready to gamble on something like this?” asked Eberstadt. “I find it fascinating that he would gamble on six or seven decades of talk about unification by changing the party line of his grandfather,” Kim Il Sung, and his father, Kim Jong Il, “who were both talking about unification.”

Renouncing reunification of North and South Korea by negotiations and proclaiming South Korea “our principal enemy,” he ordered the destruction of the famous reunification arch that spanned the main entrance into Pyongyang from the south as a symbol of his shifting policy. The arch, which was completed in 2001, showed two women in traditional Korean dress leaning toward each other high above the highway, their outstretched hands holding an image of a map of all Korea. It was a familiar sight to visitors to the capital.

“It’s a U.S. election year and the North Korean leaders always like to make themselves heard on U.S. election years.”

— Victor Cha

The bluff and bluster, the rhetoric, the testing of ever more sophisticated weaponry prompts the critical question: Could this be the year Kim launches deadly missiles? The realization that Kim has America’s two biggest, deadliest foes, both nuclear superpowers, on his side has bolstered the argument.

“Knowing China and Russia have his back at the U.N. Security Council could embolden Kim Jong Un to even more provocative behavior,” Bruce Klingner, former CIA analyst and long-time Korea expert at the Heritage Foundation, told The Daily Beast. “North Korea could conduct its long-awaited seventh nuclear test—either of a new generation of tactical battlefield nuclear weapons or Kim’s promised ‘super-large’ weapon.”

China and Russia are sure to oppose all attempts at censuring or slapping new U.N. sanctions on North Korea, much less enforcing those already in place, but China’s President Xi Jinping is assumed to have dissuaded Kim from ordering a nuclear test since September 2017 when a hydrogen bomb blew up much of a mountain.

Alternatively, we may expect Kim to resort to more missile and artillery tests—and also foment “provocations” endangering “enemy” troops—“in the run-up to annual U.S.-South Korean large-scale military exercises in March,” said Klingner. In recent weeks he’s ordered the test of an underwater drone that might be tipped with a warhead, he’s sent a spy satellite circling the Earth, and he’s got a new reprocessing facility several times bigger than the old five-megawatt reactor up and running at the nuclear complex at Yongbyon 60 miles north of Pyongyang.

After North Korean gunners fired several cruise missiles off its west and east coasts, Pyongyang’s Korean Central News Agency said Kim supervised the launch of a new model submarine-launched cruise missile that soared over the waters between North Korea and Japan for two hours and three minutes.

Such tests have become almost routine under a regime that’s conducted more than 100 of them in the past two years. The overriding concern is that the missiles—and artillery—are growing ever more accurate and powerful as Kim looks for a pretext to finally shift from rhetoric about war to the real thing.

“The regime could also launch an ICBM over Japan and demonstrate multiple-warhead or re-entry vehicle capabilities,” Klingner observed. “To date, all ICBM launches have been on a near-vertical lofted trajectory to avoid flying over other countries.”

That estimate supports an analysis issued last year by the National Intelligence Council forecasting that Kim “most likely will employ a variety of coercive methods and threats of aggression” and “may be willing to take greater conventional military risks, believing that nuclear weapons will deter an unacceptably strong U.S. or South Korean response.”

All of which leads Victor Cha, long-time Korea analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, to observe there are “many rungs in the escalation ladder that Kim could climb before all-out war”—meaning he could look for ways to stir up fears among American policy-makers that may be forgetting him while focusing on shooting wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

Possibly the strongest sign that Kim cannot be totally serious when it comes to waging war, however, is that he’s selling missiles along with artillery shells and other weaponry to Russia that he might not want to spare if he were serious about preparing for attack.

“Why would he be hawking all of his ammo to Putin if he was about to go to war?” Cha asked. “This is not to say he won’t be firing a lot of missiles this year. It’s a U.S. election year and the North Korean leaders always like to make themselves heard on U.S. election years.”

Klingner agrees that the ammo sale is a clue. “While some experts speculate that Kim Jong Un has already made the strategic decision to go to war, Pyongyang would not have sent massive amounts of artillery munitions as well as dozens of its new KN-23 missiles to Russia if it were contemplating starting a war with South Korea,” he told The Daily Beast.

Rather, he said, it’s “more probable” that he’ll instigate “another tactical-level military clash along the demilitarized zone or maritime Northern Limit Line”—the line in the Yellow Sea below which North Korean vessels are banned. He may look for a quick hit, such as two attacks in the Yellow Sea in 2010 in which the South Korean frigate Cheonan was sunk by a torpedo, killing 46 sailors, and a small island off the North’s southwestern coast was shelled, killing two Korean marines and two contract workers.

It’s the likelihood of surprise as Kim looks for leverage in an American election year that arouses the worst fears—that and the possibility that an isolated shock attack could quickly escalate on the wings of Kim’s happiness over his deal with the Russians.

Then too, Kim, under severe pressure domestically to prove he’s a dynamic leader capable of relieving the poverty and nagging hunger that pervades the lives of most of the North’s 25-26 million people, may try to enhance his power and prestige by finally attacking the South.

Kim “might very well be under severe stress internally,” said David Maxwell, vice president of the Center for Asia-Pacific Strategy. “He may perceive threats from the elite and from the Korean people in the north.”

The real danger “lies not with a calculated deliberate attack,” said Maxwell, a retired army colonel who did five tours in South Korea with the special forces. “If he cannot maintain internal control and perceives the threat is unmanageable, he may believe his only option is to execute his campaign plan to unify the peninsula by force in order to ensure regime survival.”

Or perhaps Kim is following the old playbook of revving up a sense of genuine crisis, getting diplomats scurrying hither and yon, dragging the U.S., South Korea, and Japan reluctantly into yet another talkfest reminiscent of the six-party talks, including the U.S. and both Koreas as well as China, Russia and Japan. They sputtered on for nearly seven years, from 2002 to 2009 when North Korea cut them off after Kim Jong Il ordered the North’s second nuclear test in May of that year, two and a half years after the first nuclear test in October 2006.

Kim Jong Un, like his father and grandfather, “always wants to dominate the whole Korean Peninsula,” said Choi Jin-wook, president of the Center for Strategic and Cultural Studies in Seoul. “Negotiating with the U.S. and neutralizing is his goal.” Choi argues that Kim, exploiting “the sensitive point between Washington’s diplomatic reluctance and military capacity,” figures the U.S. “is reluctant to be engaged in another conflict” amid wars in Gaza and Ukraine. “Kim wants to make a provocation to negotiate with the U.S.,” said Choi.

Continued......

Posted for fair use......

Why Some Insiders Fear This Is the Year North Korea Will Fire Nukes

In his most intensive drive for power over the Korean peninsula since his father’s death more than 12 years ago,

dnyuz.com

Why Some Insiders Fear This Is the Year North Korea Will Fire Nukes

February 5, 2024in News, World

In his most intensive drive for power over the Korean peninsula since his father’s death more than 12 years ago, North Korea’s Kim Jong Un is mounting a blitzkrieg of weapons tests and rhetoric. His goal: to convince both his own people and his enemies that he’ll risk a second Korean War to reunite North and South Korea under one-man rule.

Buoyed by his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Kim is shipping artillery shells and missiles for Russian forces bogged down in Ukraine while spreading fears of a grand plan to take over South Korea. The dream is to fulfill the vision of his grandfather, regime founder Kim Il Sung, who tried and failed to conquer the South in the first Korean War.

Kim’s big talk, his decision to give up all pretense of dealing with South Korea, above all his dedication to a nuclear program capable of inflicting mass death from Northeast Asia to the U.S., has experts forecasting more and bigger weapons tests—on top of unremitting threats.

“It looks like Kim Jong Un is talking about absorption by conquest,” said Nicholas Eberstadt, long-time researcher at the American Enterprise Institute. “What’s changed since last year? We know that North Korea is preparing for nuclear war on the Korean peninsula.”

Eberstadt, talking to The Daily Beast, qualified that bold assertion by noting that South Korea, with a strong economy and a well-equipped military establishment, supported by its American ally, is far more powerful than the impoverished North Korea, whose 1.2 million troops are underfed, ill-equipped, and often used as slave labor on farms and construction projects.

“Do they really think they are ready to gamble on something like this?” asked Eberstadt. “I find it fascinating that he would gamble on six or seven decades of talk about unification by changing the party line of his grandfather,” Kim Il Sung, and his father, Kim Jong Il, “who were both talking about unification.”

Renouncing reunification of North and South Korea by negotiations and proclaiming South Korea “our principal enemy,” he ordered the destruction of the famous reunification arch that spanned the main entrance into Pyongyang from the south as a symbol of his shifting policy. The arch, which was completed in 2001, showed two women in traditional Korean dress leaning toward each other high above the highway, their outstretched hands holding an image of a map of all Korea. It was a familiar sight to visitors to the capital.

“It’s a U.S. election year and the North Korean leaders always like to make themselves heard on U.S. election years.”

— Victor Cha

The bluff and bluster, the rhetoric, the testing of ever more sophisticated weaponry prompts the critical question: Could this be the year Kim launches deadly missiles? The realization that Kim has America’s two biggest, deadliest foes, both nuclear superpowers, on his side has bolstered the argument.

“Knowing China and Russia have his back at the U.N. Security Council could embolden Kim Jong Un to even more provocative behavior,” Bruce Klingner, former CIA analyst and long-time Korea expert at the Heritage Foundation, told The Daily Beast. “North Korea could conduct its long-awaited seventh nuclear test—either of a new generation of tactical battlefield nuclear weapons or Kim’s promised ‘super-large’ weapon.”

China and Russia are sure to oppose all attempts at censuring or slapping new U.N. sanctions on North Korea, much less enforcing those already in place, but China’s President Xi Jinping is assumed to have dissuaded Kim from ordering a nuclear test since September 2017 when a hydrogen bomb blew up much of a mountain.

Alternatively, we may expect Kim to resort to more missile and artillery tests—and also foment “provocations” endangering “enemy” troops—“in the run-up to annual U.S.-South Korean large-scale military exercises in March,” said Klingner. In recent weeks he’s ordered the test of an underwater drone that might be tipped with a warhead, he’s sent a spy satellite circling the Earth, and he’s got a new reprocessing facility several times bigger than the old five-megawatt reactor up and running at the nuclear complex at Yongbyon 60 miles north of Pyongyang.

After North Korean gunners fired several cruise missiles off its west and east coasts, Pyongyang’s Korean Central News Agency said Kim supervised the launch of a new model submarine-launched cruise missile that soared over the waters between North Korea and Japan for two hours and three minutes.

Such tests have become almost routine under a regime that’s conducted more than 100 of them in the past two years. The overriding concern is that the missiles—and artillery—are growing ever more accurate and powerful as Kim looks for a pretext to finally shift from rhetoric about war to the real thing.

“The regime could also launch an ICBM over Japan and demonstrate multiple-warhead or re-entry vehicle capabilities,” Klingner observed. “To date, all ICBM launches have been on a near-vertical lofted trajectory to avoid flying over other countries.”

That estimate supports an analysis issued last year by the National Intelligence Council forecasting that Kim “most likely will employ a variety of coercive methods and threats of aggression” and “may be willing to take greater conventional military risks, believing that nuclear weapons will deter an unacceptably strong U.S. or South Korean response.”

All of which leads Victor Cha, long-time Korea analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, to observe there are “many rungs in the escalation ladder that Kim could climb before all-out war”—meaning he could look for ways to stir up fears among American policy-makers that may be forgetting him while focusing on shooting wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

Possibly the strongest sign that Kim cannot be totally serious when it comes to waging war, however, is that he’s selling missiles along with artillery shells and other weaponry to Russia that he might not want to spare if he were serious about preparing for attack.

“Why would he be hawking all of his ammo to Putin if he was about to go to war?” Cha asked. “This is not to say he won’t be firing a lot of missiles this year. It’s a U.S. election year and the North Korean leaders always like to make themselves heard on U.S. election years.”

Klingner agrees that the ammo sale is a clue. “While some experts speculate that Kim Jong Un has already made the strategic decision to go to war, Pyongyang would not have sent massive amounts of artillery munitions as well as dozens of its new KN-23 missiles to Russia if it were contemplating starting a war with South Korea,” he told The Daily Beast.

Rather, he said, it’s “more probable” that he’ll instigate “another tactical-level military clash along the demilitarized zone or maritime Northern Limit Line”—the line in the Yellow Sea below which North Korean vessels are banned. He may look for a quick hit, such as two attacks in the Yellow Sea in 2010 in which the South Korean frigate Cheonan was sunk by a torpedo, killing 46 sailors, and a small island off the North’s southwestern coast was shelled, killing two Korean marines and two contract workers.

It’s the likelihood of surprise as Kim looks for leverage in an American election year that arouses the worst fears—that and the possibility that an isolated shock attack could quickly escalate on the wings of Kim’s happiness over his deal with the Russians.

Then too, Kim, under severe pressure domestically to prove he’s a dynamic leader capable of relieving the poverty and nagging hunger that pervades the lives of most of the North’s 25-26 million people, may try to enhance his power and prestige by finally attacking the South.

Kim “might very well be under severe stress internally,” said David Maxwell, vice president of the Center for Asia-Pacific Strategy. “He may perceive threats from the elite and from the Korean people in the north.”

The real danger “lies not with a calculated deliberate attack,” said Maxwell, a retired army colonel who did five tours in South Korea with the special forces. “If he cannot maintain internal control and perceives the threat is unmanageable, he may believe his only option is to execute his campaign plan to unify the peninsula by force in order to ensure regime survival.”

Or perhaps Kim is following the old playbook of revving up a sense of genuine crisis, getting diplomats scurrying hither and yon, dragging the U.S., South Korea, and Japan reluctantly into yet another talkfest reminiscent of the six-party talks, including the U.S. and both Koreas as well as China, Russia and Japan. They sputtered on for nearly seven years, from 2002 to 2009 when North Korea cut them off after Kim Jong Il ordered the North’s second nuclear test in May of that year, two and a half years after the first nuclear test in October 2006.

Kim Jong Un, like his father and grandfather, “always wants to dominate the whole Korean Peninsula,” said Choi Jin-wook, president of the Center for Strategic and Cultural Studies in Seoul. “Negotiating with the U.S. and neutralizing is his goal.” Choi argues that Kim, exploiting “the sensitive point between Washington’s diplomatic reluctance and military capacity,” figures the U.S. “is reluctant to be engaged in another conflict” amid wars in Gaza and Ukraine. “Kim wants to make a provocation to negotiate with the U.S.,” said Choi.

Continued......

Continued.......

“Provocation” is a watchword that analysts routinely predict. Two of them, Robert Carlin, a former chief of the Northeast Asia Division in the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the State Department, and Siegfried S. Hecker, former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, believe the word is not strong enough for what lies ahead.

“The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950” when Kim’s grandfather, Kim Il Sung, ordered his troops to invade South Korea, they write in 38 North, a website that tracks North Korea from Washington. They may not know “when or how Kim plans to pull the trigger,” but say “the danger is already far beyond the routine warnings in Washington, Seoul and Tokyo about Pyongyang’s provocations,” and they don’t see the outpouring of harsh words from Pyongyang over the past year “as typical bluster.”

Pyongyang-watchers contacted by The Daily Beast, however, take a more nuanced view.

“At least some of this rhetoric is in response to the new allied focus on extended deterrence,” said Bruce Bechtol, former Defense Department intelligence analyst and author of numerous books and studies on North Korea’s leadership. The U.S., South Korea and Japan have formed a “nuclear consultative group” and “formalized much of the planning for how to respond to a North Korean nuclear attack,” said Bechtol. “Clearly Pyongyang sees this as a threat.”

Bechtol does not, however, “see North Korea launching a large-scale, ‘bolt-out-of-the-blue’ attack on South Korea, or on the USA using ICBM’s.” Rather, he predicted “renewed and focused testing of North Korean ballistic missile systems and perhaps even a nuclear test.”

“The North Koreans likely asked the Russians for advanced ballistic missile technology as part of the payment for the large numbers of artillery, shells, rockets, and SRBM’s that North Korea sold to Moscow,” he said. “Thus, the North Koreans will be anxious to show off that technology in 2024.”

“But an attack on the South, or the USA?” Bechtol asked. “Highly, highly unlikely,” he said, dismissing Hecker as “very smart on nuclear weapons” but “hardly an international security expert.” And, he added, “It goes without saying (but I will say it anyway) that I disagree with Carlin as well.”

At Ewha University in Seoul, Leif-Eric Easley, professor of international relations, noted that “Pyongyang has taken disproportionate steps including missile tests it says are preparations for nuclear war, while abolishing organizations for inter-Korean exchanges and labeling Seoul an enemy to be defeated.” Still, he said, “Many of Kim’s recent pronouncements are likely for domestic political consumption.”

In fact, said Easley, “South Koreans have, for many years, suspected that there could be no denuclearization and peaceful reunification as long as the Kim regime rules North Korea.” By “formalizing this in law, dashing hopes for reconciliation that had facilitated inter-Korean diplomacy, Kim’s motivation is probably not to start a war but to blame South Korea for the costly policies he employs to maintain power.”

“We should not downplay whatever comes from Kim’s mouth.”

— Kim Kisam, ex-South Korean National Intelligence Service

Evans Revere, who served for years as a senior U.S. diplomat in both Seoul and Tokyo, attributes what he calls Kim’s “latest gambit” to “four words: exasperation, fear, arrogance, and cunning.”

Kim, he said, “has found, much to his chagrin,” that South Korea’s current government, under the conservative President Yoon Seoul-yul, “is never going to play the old game of offering unilateral concessions, turning the other cheek when Pyongyang insults and threatens the South, accommodating North Korean excesses, and bending over backwards—all to keep dialogue going at almost any price.”

It’s for that reason, Revere surmised, that Kim “has decided to flip the script and declare that South Korea is not only no longer a partner for dialogue, reconciliation, and eventual reunification” but “is now an enemy state, an alien country that does not deserve to be called “Korean,” and a proper target of North Korea’s military might and its desire now to forcibly subjugate the South at the right moment.”

So doing, said Revere, Kim has “made clear that everything, including violence, is now fair game when it comes to dealing with the South.” His “more aggressive posture, missile testing, and new nuclear and conventional military moves are also driven by his concern” that U.S. relations with South Korea “are closer and stronger than ever” while trilateral cooperation among the U.S., South Korea, and Japan, “is growing quickly, U.S.-allied joint exercises are more robust and realistic than ever, and U.S. military power on and around the Korean Peninsula is robust and ready.”

Revere derides, however, what he called “the breathless tone of some experts declaring that North Korea is ‘preparing for war’”—a reference to the Hecker-Carlin article. North Korea’s “goal is survival, not suicide,” he told The Daily Beast. “The military balance is not in his favor and never will be. Kim Jong Un knows how another Korean War would end. He does not wish his “paradise” turned into an ash heap.”

Looking toward more endless talks that go nowhere, however, Revere said Kim “also knows that enough breast-beating, over-the-top-rhetoric, and threats will give the U.S. and its allies pause.”

He’s “giddy with confidence,” said Revere, because of “flourishing ties with Russia, Moscow’s payment for North Korean weapons, and visions of getting Russian technical support for its missile, space, and other programs.” Russia and China also “provide reliable cover” in the U.N. Security Council, “shielding him from efforts to impose new UNSC sanctions.”

Just as important, as intimated by Hecker and Carlin, is that “North Korea’s survival skills do not fail to impress,” said Revere. “Kim’s warlike rhetoric has convinced some American critics of Biden administration policy, who once argued that Pyongyang’s moves were purely defensive and North Korea only wanted better relations with the U.S., that North Korea is now on the path to an offensive war.”

Kim “must be smiling at his good fortune in enlisting the support of this key U.S. constituency in making the case that it is Washington, and not Pyongyang, that is at fault,” said Revere.

Moon Chung-in, a notable professor who advised the previous liberal South Korean administration on dealing with North Korea, has long espoused dialogue with the North. He disagrees with the rather extreme views of Hecker and Carlin but worries about incidents resulting from errors and miscalculations.

“War by plan is not imminent,” he told a forum at the Korea Society in New York. “Naval clashes can occur any time. North Korea has 12,000 artillery pieces along the demilitarized zone. We should come up with measures for stability and reducing risks.”

Bruce Bennett, veteran Korea analyst at the RAND Corporation, sees the aggressive policies of South Korea’s conservative President Yoon Seok-yul, also as challenging Kim to react harshly.

Yoon, after enthusiastically approving joint war games with American troops after his leftist predecessor, Moon Jae-in, stopped them, “has threatened major retaliation against any North Korean attack,” said Bennett. “Since Kim wants to undermine the U.S. alliance, Kim may try to further this objective by doing some form of limited attack, hoping for an escalated retaliation against which he will escalate, hoping to make Yoon’s actions appear reckless.”

The risks for Kim are high. “One problem Kim faces is identifying an initial attack that is sufficiently limited and/or plausibly deniable,” said Bennett. South Koreans “would find a deadly North Korean missile attack too extreme, likely yielding the opposite of the effect Kim wants.

Bennett cites any number of scenarios for a North Korean response short of all-out war. “Kim might try a non-lethal missile attack, such as firing a North Korean theater missile at an uninhabited island,” he said. Or Kim “could try a special forces attack, hoping that his personnel would not get caught. A third alternative would be a major cyber attack”—crippling a bank or disrupting the South Korean power grid.

“A North Korean attack becomes far more dangerous once Kim roughly doubles his current nuclear weapon and ICBM capabilities,” Bennett said, “but that is several years off.”

Markus Garlauskas, at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, citing North Korea’s “history of limited violence,” believes the U.S. and South Korea need “to have the capability of quick retaliation below the level of full-scale war.” It’s “in that space between provocation of war,” he said at the Korea Society forum, “where we should be focusing.”

The Chinese are believed to have been dissuading North Korea from staging another nuclear test. For all his talk, Kim has held off on what would be the North’s seventh nuclear test—its first since September 2017. “They were definitely talking about concerns about a nuclear test,” said Susan Thornton, a former State Department official, now at Brookings. Moreover, “They have been unhappy about the weapons sales to Russia.” Still, she said, “they were also unhappy about the U.S. approach to North Korea and think there should be discussions going.”

Bottom line: Ankit Pandit, nuclear expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, expects Kim “to keep up his missile exercises and developmental tests this year.” South Korea and the U.S. “should remain vigilant to possible limited attacks short of all-out war, too,” he warned. “Kim appears especially confident in the current context.”

There’s no denying Kim may stage an attack when least expected, as when North Korea invaded the South in June 1950. Kim Kisam, formerly with South Korea’s National Intelligence Service, told The Daily Beast, “We should not downplay whatever comes from his mouth.”

The North Korean leader is “now equipped with nukes and has piled up plenty of vehicles,” said Kim Kisam. “Highly likely, he maintains dozens of underground tunnels for surprise attacks. The more he feels his situation is dire, the more he’s tempted to attack the South.”

The post Why Some Insiders Fear This Is the Year North Korea Will Fire Nukes appeared first on The Daily Beast.

“Provocation” is a watchword that analysts routinely predict. Two of them, Robert Carlin, a former chief of the Northeast Asia Division in the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the State Department, and Siegfried S. Hecker, former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, believe the word is not strong enough for what lies ahead.

“The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950” when Kim’s grandfather, Kim Il Sung, ordered his troops to invade South Korea, they write in 38 North, a website that tracks North Korea from Washington. They may not know “when or how Kim plans to pull the trigger,” but say “the danger is already far beyond the routine warnings in Washington, Seoul and Tokyo about Pyongyang’s provocations,” and they don’t see the outpouring of harsh words from Pyongyang over the past year “as typical bluster.”

Pyongyang-watchers contacted by The Daily Beast, however, take a more nuanced view.

“At least some of this rhetoric is in response to the new allied focus on extended deterrence,” said Bruce Bechtol, former Defense Department intelligence analyst and author of numerous books and studies on North Korea’s leadership. The U.S., South Korea and Japan have formed a “nuclear consultative group” and “formalized much of the planning for how to respond to a North Korean nuclear attack,” said Bechtol. “Clearly Pyongyang sees this as a threat.”

Bechtol does not, however, “see North Korea launching a large-scale, ‘bolt-out-of-the-blue’ attack on South Korea, or on the USA using ICBM’s.” Rather, he predicted “renewed and focused testing of North Korean ballistic missile systems and perhaps even a nuclear test.”

“The North Koreans likely asked the Russians for advanced ballistic missile technology as part of the payment for the large numbers of artillery, shells, rockets, and SRBM’s that North Korea sold to Moscow,” he said. “Thus, the North Koreans will be anxious to show off that technology in 2024.”

“But an attack on the South, or the USA?” Bechtol asked. “Highly, highly unlikely,” he said, dismissing Hecker as “very smart on nuclear weapons” but “hardly an international security expert.” And, he added, “It goes without saying (but I will say it anyway) that I disagree with Carlin as well.”

At Ewha University in Seoul, Leif-Eric Easley, professor of international relations, noted that “Pyongyang has taken disproportionate steps including missile tests it says are preparations for nuclear war, while abolishing organizations for inter-Korean exchanges and labeling Seoul an enemy to be defeated.” Still, he said, “Many of Kim’s recent pronouncements are likely for domestic political consumption.”

In fact, said Easley, “South Koreans have, for many years, suspected that there could be no denuclearization and peaceful reunification as long as the Kim regime rules North Korea.” By “formalizing this in law, dashing hopes for reconciliation that had facilitated inter-Korean diplomacy, Kim’s motivation is probably not to start a war but to blame South Korea for the costly policies he employs to maintain power.”

“We should not downplay whatever comes from Kim’s mouth.”

— Kim Kisam, ex-South Korean National Intelligence Service

Evans Revere, who served for years as a senior U.S. diplomat in both Seoul and Tokyo, attributes what he calls Kim’s “latest gambit” to “four words: exasperation, fear, arrogance, and cunning.”

Kim, he said, “has found, much to his chagrin,” that South Korea’s current government, under the conservative President Yoon Seoul-yul, “is never going to play the old game of offering unilateral concessions, turning the other cheek when Pyongyang insults and threatens the South, accommodating North Korean excesses, and bending over backwards—all to keep dialogue going at almost any price.”

It’s for that reason, Revere surmised, that Kim “has decided to flip the script and declare that South Korea is not only no longer a partner for dialogue, reconciliation, and eventual reunification” but “is now an enemy state, an alien country that does not deserve to be called “Korean,” and a proper target of North Korea’s military might and its desire now to forcibly subjugate the South at the right moment.”

So doing, said Revere, Kim has “made clear that everything, including violence, is now fair game when it comes to dealing with the South.” His “more aggressive posture, missile testing, and new nuclear and conventional military moves are also driven by his concern” that U.S. relations with South Korea “are closer and stronger than ever” while trilateral cooperation among the U.S., South Korea, and Japan, “is growing quickly, U.S.-allied joint exercises are more robust and realistic than ever, and U.S. military power on and around the Korean Peninsula is robust and ready.”

Revere derides, however, what he called “the breathless tone of some experts declaring that North Korea is ‘preparing for war’”—a reference to the Hecker-Carlin article. North Korea’s “goal is survival, not suicide,” he told The Daily Beast. “The military balance is not in his favor and never will be. Kim Jong Un knows how another Korean War would end. He does not wish his “paradise” turned into an ash heap.”

Looking toward more endless talks that go nowhere, however, Revere said Kim “also knows that enough breast-beating, over-the-top-rhetoric, and threats will give the U.S. and its allies pause.”

He’s “giddy with confidence,” said Revere, because of “flourishing ties with Russia, Moscow’s payment for North Korean weapons, and visions of getting Russian technical support for its missile, space, and other programs.” Russia and China also “provide reliable cover” in the U.N. Security Council, “shielding him from efforts to impose new UNSC sanctions.”

Just as important, as intimated by Hecker and Carlin, is that “North Korea’s survival skills do not fail to impress,” said Revere. “Kim’s warlike rhetoric has convinced some American critics of Biden administration policy, who once argued that Pyongyang’s moves were purely defensive and North Korea only wanted better relations with the U.S., that North Korea is now on the path to an offensive war.”

Kim “must be smiling at his good fortune in enlisting the support of this key U.S. constituency in making the case that it is Washington, and not Pyongyang, that is at fault,” said Revere.

Moon Chung-in, a notable professor who advised the previous liberal South Korean administration on dealing with North Korea, has long espoused dialogue with the North. He disagrees with the rather extreme views of Hecker and Carlin but worries about incidents resulting from errors and miscalculations.

“War by plan is not imminent,” he told a forum at the Korea Society in New York. “Naval clashes can occur any time. North Korea has 12,000 artillery pieces along the demilitarized zone. We should come up with measures for stability and reducing risks.”

Bruce Bennett, veteran Korea analyst at the RAND Corporation, sees the aggressive policies of South Korea’s conservative President Yoon Seok-yul, also as challenging Kim to react harshly.

Yoon, after enthusiastically approving joint war games with American troops after his leftist predecessor, Moon Jae-in, stopped them, “has threatened major retaliation against any North Korean attack,” said Bennett. “Since Kim wants to undermine the U.S. alliance, Kim may try to further this objective by doing some form of limited attack, hoping for an escalated retaliation against which he will escalate, hoping to make Yoon’s actions appear reckless.”

The risks for Kim are high. “One problem Kim faces is identifying an initial attack that is sufficiently limited and/or plausibly deniable,” said Bennett. South Koreans “would find a deadly North Korean missile attack too extreme, likely yielding the opposite of the effect Kim wants.

Bennett cites any number of scenarios for a North Korean response short of all-out war. “Kim might try a non-lethal missile attack, such as firing a North Korean theater missile at an uninhabited island,” he said. Or Kim “could try a special forces attack, hoping that his personnel would not get caught. A third alternative would be a major cyber attack”—crippling a bank or disrupting the South Korean power grid.

“A North Korean attack becomes far more dangerous once Kim roughly doubles his current nuclear weapon and ICBM capabilities,” Bennett said, “but that is several years off.”

Markus Garlauskas, at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, citing North Korea’s “history of limited violence,” believes the U.S. and South Korea need “to have the capability of quick retaliation below the level of full-scale war.” It’s “in that space between provocation of war,” he said at the Korea Society forum, “where we should be focusing.”

The Chinese are believed to have been dissuading North Korea from staging another nuclear test. For all his talk, Kim has held off on what would be the North’s seventh nuclear test—its first since September 2017. “They were definitely talking about concerns about a nuclear test,” said Susan Thornton, a former State Department official, now at Brookings. Moreover, “They have been unhappy about the weapons sales to Russia.” Still, she said, “they were also unhappy about the U.S. approach to North Korea and think there should be discussions going.”

Bottom line: Ankit Pandit, nuclear expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, expects Kim “to keep up his missile exercises and developmental tests this year.” South Korea and the U.S. “should remain vigilant to possible limited attacks short of all-out war, too,” he warned. “Kim appears especially confident in the current context.”

There’s no denying Kim may stage an attack when least expected, as when North Korea invaded the South in June 1950. Kim Kisam, formerly with South Korea’s National Intelligence Service, told The Daily Beast, “We should not downplay whatever comes from his mouth.”

The North Korean leader is “now equipped with nukes and has piled up plenty of vehicles,” said Kim Kisam. “Highly likely, he maintains dozens of underground tunnels for surprise attacks. The more he feels his situation is dire, the more he’s tempted to attack the South.”

The post Why Some Insiders Fear This Is the Year North Korea Will Fire Nukes appeared first on The Daily Beast.

northern watch

TB Fanatic

northern watch

TB Fanatic

jward

passin' thru

EndGameWW3

@EndGameWW3

Ships from US, Australia and Japan conduct joint drills in South China Sea in defiance of Beijing

@EndGameWW3

Ships from US, Australia and Japan conduct joint drills in South China Sea in defiance of Beijing

northern watch

TB Fanatic

jward

passin' thru

Indo-Pacific News - Geo-Politics & Defense News

@IndoPac_Info

#Philippines gunning for fast and massive military build-up

Top brass angling for $36 billion defense spending package to include multiple submarines and other modern assets to point at #China

“We are not satisfied with minimum [deterrence capability alone]…movement is life, stagnation is death,” Colonel Micheal Logico, a top strategist at the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), recently told this reporter when asked about the country’s evolving defense strategy.

“We need to elevate ourselves into a world-class armed forces,” he added.

Confronting a mighty China, the Philippines is undergoing a once-in-a-century defense buildup that if all goes to plan could transform it into a formidable military “middle power.”

This year, top Philippine defense officials have announced their decision to pursue the acquisition of multiple submarines as part of a massive US$36 billion defense spending package.

“We do not only need one submarine, we need two or three [at least],” Commodore Roy Vincent Trinidad, spokesperson of the Philippine Navy for the West Philippines, recently told media. Under “Horizon Three”, the third phase of a 15-year-old defense modernization plan that began in 2012, the Philippines is also set to acquire modern fighter jets, warships and missile systems.

Next month, the Philippines is also set to receive India’s much-vaunted Brahmos supersonic missile system, which is seen as a likely precursor to even more sophisticated acquisitions in the future.

“It is a real game-changer because it brings the Philippines to the supersonic age. For the first time in our history, the Philippines will have three batteries of supersonic cruise missiles that have a speed of (Mach 2.8) or almost 3x (times) the speed of sound,” said National Security Council spokesman Jonathan Malaya.

The Southeast Asian nation wants to develop its conventional and asymmetric military capabilities as it prepares for multiple contingencies in the region vis-à-vis China, including in both the hotly-contested South China Sea as well as over nearby Taiwan, which is only separated by the narrow Bashi Channel from northern Philippine provinces.

Now boasting Southeast Asia’s fastest-growing economy, the Philippines finally has more financial resources to invest in its long-neglected armed forces, which half a century ago were the envy of the region with state-of-the-art American weapons and fighter jets.

Well into the 1970s, the Philippines intimidated its smaller neighbors and unilaterally built military facilities in the Spratly group of islands.

At one point, the Richard Nixon administration worried that it could get dragged into conflict with other claimant states due to its mutual defense treaty with a self-aggrandizing ally, thus Washington’s long-term policy of strategic ambiguity on the South China Sea disputes.

At the height of hubris, the Philippines even contemplated the invasion of Malaysia in order to wrest back control of Sabah, an oil-rich island that once belonged to the Sultanate of Sulu, now part of the Philippine Republic.

But chronic corruption, political instability and decades-long insurgencies in the restive island of Mindanao steadily corroded and spent the Philippines’ military capabilities.

By the end of the 20th century, the Southeast Asian nation, among the world’s largest archipelagos, had among the smallest and most antiquated navies in the region.

The Philippine Army, battling decades-long Muslim and communist insurgencies, gobbled up much of the AFP’s resources. For years, the Philippines didn’t even possess a single supersonic fighter jet.

Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, the Philippines served as a “second front” for the George W Bush administration’s “Global War on Terror”, further reinforcing gaps in Philippine military capabilities.

But things began to change under President Benigno Aquino III (2010-2016), who implemented the Revised AFP Modernization Act, which sought to rapidly modernize the Philippine Navy and Air Force.

Within a few years, the Philippines had acquired modern fighters from South Korea under a $415.7 million package. The Philippine Navy (PN), meanwhile, acquired increasingly modern warships, most notably the BRP Gregorio Del Pilar (PF15) and BRP Ramon Alcaraz (PF16), Hamilton and Hero-class cutters worth up to $400 million.

Defense spending increased by 36% between 2004 and 2013, with the year 2015 seeing close to a 30% year-on-year increase.

To boost its ally’s defense modernization, Washington increased its Foreign Military Financing to the Philippines over the years. Other key partners such as Japan, meanwhile, provided multi-role patrol vessels to the Philippine Coast Guard while South Korea donated a Pohang-class corvette to PN.

Beyond minimum deterrence

Initially, the Philippines was hoping to simply achieve a “minimum credible defense” capability vis-a-vis rivals such as China.

Despite many hurdles and delays, however, the Southeast Asian nation’s military modernization campaign now aims at building a 21st-century armed forces en route to becoming a full-fledged “middle power.”

Last year, the Philippines overtook Vietnam to become the swiftest-growing economy in Southeast Asia, a trend that some expect to continue well into the future.

This places the Philippines on a path to becoming among the biggest economies in the region, thus generating more economic resources for a defense build-up.

Accordingly, the Philippines has pressed ahead with a revised 10-year modernization plan worth 2 trillion pesos ($35.62 billion) to finance the acquisition of state-of-the-art weapons including submarines.

“[W]e are embarking into what we call the ‘ReHorizoned 3’ capability enhancement and modernization program where the President recently approved an array of capabilities,” Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro Jr said.

“The Armed Forces will transition initially to enable itself to guarantee, as much as possible, Philippine corporations and those authorized by the Philippine environment the unimpeded and peaceful exploration and exploitation of all natural resources within our exclusive economic zone and other areas where we have jurisdiction,” he added.

With that signaling, several countries are jockeying to win multi-billion dollar defense contracts with the Philippines. The French, who are also exploring a visiting forces agreement-style deal with Manila, seem to be ahead in the line.

France’s Naval Group is offering two diesel-electric Scorpene-class submarines, similar to those operated by neighboring Malaysia.

Navantia, a Spanish government-affiliated company, Navantia, is also in the running and has offered two S80-class Isaac Peral submarines with an estimated value of $1.7 billion. The Spanish have also offered to build a submarine base and other necessary logistics for the boats.

South Korea, already a major defense supplier to Manila, is also jostling for the sub deal. Hanwha Ocean (formerly known as DSME) is offering its Jang Bogo-III submarines, which boast guided-missile systems, advanced propulsion and lithium-ion battery technology that makes them particularly stealthy.

South Korea has already supplied the Philippines’ with its most advanced warships and fighter jets, making it a trusted partner amid the rival big-ticket bidding.

“For so long, the Philippine military has also been considered the weakest in our region. With the acquisition of [submarines], we will no longer be called the weakest,” National Security Council spokesman Jonathan Malaya said in a mixture of English and Filipino when asked about the strategic implications of the submarine acquisition plans.

“We will now become a middle power in terms of our armed capabilities and that is a game-changer because that will increase our defense posture,” he added.

@IndoPac_Info

#Philippines gunning for fast and massive military build-up

Top brass angling for $36 billion defense spending package to include multiple submarines and other modern assets to point at #China

“We are not satisfied with minimum [deterrence capability alone]…movement is life, stagnation is death,” Colonel Micheal Logico, a top strategist at the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), recently told this reporter when asked about the country’s evolving defense strategy.

“We need to elevate ourselves into a world-class armed forces,” he added.

Confronting a mighty China, the Philippines is undergoing a once-in-a-century defense buildup that if all goes to plan could transform it into a formidable military “middle power.”

This year, top Philippine defense officials have announced their decision to pursue the acquisition of multiple submarines as part of a massive US$36 billion defense spending package.

“We do not only need one submarine, we need two or three [at least],” Commodore Roy Vincent Trinidad, spokesperson of the Philippine Navy for the West Philippines, recently told media. Under “Horizon Three”, the third phase of a 15-year-old defense modernization plan that began in 2012, the Philippines is also set to acquire modern fighter jets, warships and missile systems.

Next month, the Philippines is also set to receive India’s much-vaunted Brahmos supersonic missile system, which is seen as a likely precursor to even more sophisticated acquisitions in the future.

“It is a real game-changer because it brings the Philippines to the supersonic age. For the first time in our history, the Philippines will have three batteries of supersonic cruise missiles that have a speed of (Mach 2.8) or almost 3x (times) the speed of sound,” said National Security Council spokesman Jonathan Malaya.

The Southeast Asian nation wants to develop its conventional and asymmetric military capabilities as it prepares for multiple contingencies in the region vis-à-vis China, including in both the hotly-contested South China Sea as well as over nearby Taiwan, which is only separated by the narrow Bashi Channel from northern Philippine provinces.

Now boasting Southeast Asia’s fastest-growing economy, the Philippines finally has more financial resources to invest in its long-neglected armed forces, which half a century ago were the envy of the region with state-of-the-art American weapons and fighter jets.

Well into the 1970s, the Philippines intimidated its smaller neighbors and unilaterally built military facilities in the Spratly group of islands.

At one point, the Richard Nixon administration worried that it could get dragged into conflict with other claimant states due to its mutual defense treaty with a self-aggrandizing ally, thus Washington’s long-term policy of strategic ambiguity on the South China Sea disputes.

At the height of hubris, the Philippines even contemplated the invasion of Malaysia in order to wrest back control of Sabah, an oil-rich island that once belonged to the Sultanate of Sulu, now part of the Philippine Republic.

But chronic corruption, political instability and decades-long insurgencies in the restive island of Mindanao steadily corroded and spent the Philippines’ military capabilities.

By the end of the 20th century, the Southeast Asian nation, among the world’s largest archipelagos, had among the smallest and most antiquated navies in the region.

The Philippine Army, battling decades-long Muslim and communist insurgencies, gobbled up much of the AFP’s resources. For years, the Philippines didn’t even possess a single supersonic fighter jet.