North Korea trapped in an endless end-game

Andrew Salmon

SEOUL – Japanese and South Korean forces

resumed naval exercises today with the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier strike group in the Sea of Japan – exercises moves that are certain to furrow already angry brows in Pyongyang.

The trilateral drills are just the latest knight’s move in a high-speed cycle of action and reaction, response and retaliation, that has elevated tensions across the region in recent days. It is a cycle that looks to be self-perpetrating.

At dawn on Thursday,

North Korea had test-fired two short-range ballistic missiles into the Sea of Japan, in what state media called a response to prior South Korea-US drills in the region.

On Wednesday, South Korean and US forces had conducted aerial and missile drills, and announced the redeployment of the USS Ronald Reagan carrier strike group to the area. Those drills, and that redeployment announcment, followed North Korea’s test-firing of an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), which flew through space over Japan on Tuesday.

Tuesday’s North Korean IRBM test, in turn, was seen as a response to drills conducted a week earlier by the Japanese and South Korean navies, in concert with the US carrier strike group which has today been conducting anti-missile drills with its two allies.

And so on and so forth,

ad infinitum.

Despite their impressive flex of military muscle, South Korea, Japan and the US have few levers to pull on Kim Jong Un, the third generation of his family to head what is a virtual fortress state.

UN Security Council resolutions and sanctions have failed to halt North Korea’s build-out of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Making bad matters worse, the prior unity in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) has collapsed.

In May, and once again Wednesday, the UNSC failed to reach an agreement over North Korea’s missile tests. Riven by the war in Ukraine and China-US decoupling, the UNSC going forward looks set to be ever more ineffectual.

Moreover, given North Korea’s isolation, there is minimal economic leverage that the US and its allies can applied. And with Pyongyang nuclear-capable since 2006, military action is off the table.

But while this

situation may frustrate politicians, diplomats, generals and wonks in Japan, South Korea and the US, their competitor is also in a

cul de sac.

Though it plays its one card in the game of nuclear poker with great skill, Pyongyang suffers from both a weak hand and the limitation of the game’s contours.

North Korea went critical in 2006 and showcased a missile capable of reaching the US mainland in 2017. But the urge to up-arm remains. With its national destiny set on a single path – the endless acquisition of ever-more powerful weapons, that suck up ever-more national resources – it is caught in its own mousetrap.

In terms of breaking its international isolation, expanding its economy, acquiring civil technologies and improving its citizens’ quality of life, there is no apparent “Plan B.”

The only possibility that offers Pyongyang a way forward – that the world will bisect into a North American/European-led liberal democratic bloc versus a Chinese-Russian-led authoritarian bloc – cannot be a strategy; it is far beyond the state’s control.

Meantime, today’s drills showcase an irony – that Pyongyang may be contributing to an outcome it greatly fears.

Throughout 2022, a confluence of factors – North Korean belligerence, growing Chinese military power and conservative administrations synching in both Seoul and Tokyo – is driving a long-term Washington goal: Upgraded Japan-South Korean-US military ties.

A warlord with his warriors: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un takes part in the First Workshop of Korean People’s Army Commanders and Political Officers in Pyongyang. Photo: KCNA VIA KNS

The race is on

Thursday morning’s test-firing of two ballistic missiles marked Pyongyang’s sixth missile test in two weeks. Amid the Ukraine war’s actual missile war, this missile test war has struggled to grab global headlines, but Pyongyang’s hefting of an IRBM over Japan did make the world sit up and take new notice.

It also compelled Seoul, Tokyo and Washington, with other like-minded states, to call a meeting of the UNSC – a meeting North Korea’s Foreign Ministry condemned. Moreover, the IRBM test

sparked a South Korean-US military reaction.

In a show of force, South Korean and US air forces detonated JDAM bunker-busting munitions on uninhabited islets in the Yellow Sea and fired missiles onto targets in the Sea of Japan.

However, South Korea’s retaliation left its public shaken and its defense officials red-faced. A home-grown South Korean missile veered off-course and detonated inside a military base near the northeastern city of Gangneung late Tuesday night. There were no casualties.

But these are tiny moves. A far bigger arms race is underway across Northeast Asia. China is muscling up in multiple areas – most recently expanding its nuclear force and launching its third heavy aircraft carrier.

Japan is working up two helicopter carriers that are under conversion to F35 carriers, expanding its stealth wing and mulling a “second strike” missile capability.

South Korea is upgrading its domestic submarines and ballistic missiles while beefing up its stealth fighters as it contemplates following Japan down the light-carrier route.

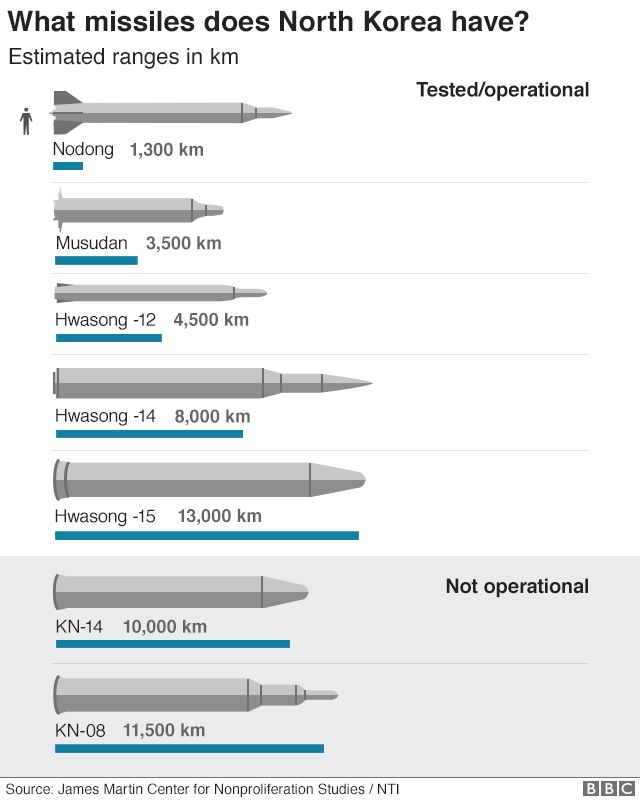

North Korea’s armory is necessarily limited by the paltry size of its economy compared with others in Northeast Asia. However, although its conventional forces lack carriers and stealth jets, its core deterrent – nuclear warheads and missile delivery systems – are hefty enough to grant it a seat at the table.

That seat needs to be maintained with constant saber-rattling, which explains – following the 2019 evaporation of North Korea-US, and collaterally, North Korean-South Korean negotiations – its extensive testing schedule. It is a schedule that has made 2022 the busiest year ever for the state’s missile sector.

Not all of these launches are responses to moves by regional competitors; 2022’s heavy launch schedule predated joint South Korea-US military drills.

With Pyongyang having announced at a party congress in 2021 a vast new armory, including hypersonic and submarine-launched missiles, and tactical and super-large nuclear weapons, it needs to test technologies, systems and manpower.

The last two especially need to conform to the new “first use” doctrine Pyongyang announced in September.

Pedestrians watch a screen displaying news reporting of North Korea’s launch of a ballistic missile in Tokyo, Japan, October 4, 2022. Photo: EPA-EFE / Kimimasa Mayama

Big bang preparations

Pyongyangologists are currently wondering when North Korea will conduct its seventh nuclear test. Satellite images have, since early this year, shown what appear to be preparations for a detonation at the country’s underground test site. Some expect the big bang after China’s upcoming party congress, which kicks off on October 16.

But while North Korea’s missile and nuclear tests may appear to signal national virility, they mask a wider national impotence, experts say.

North Korea organizes its policies under four domains – military, economic, political and diplomatic – said Go Myong-hyun, a North Korea watcher at Seoul’s Asan Institute think tank. But one is dominant.

“The military sets the pace for policy in all other domains, so all other policies derive from this domain,” Go said. “It is not measured in months – it is measured in years.”

This makes the acquisition of ever-more advanced weaponry the foremost national priority. That priority is based on regime mindset.

“The way they view this is, they see survival through strength and power, and you can never have enough power,” said Daniel Pinkston, a Seoul-resident North Korean watcher with Troy University. “We think in terms of opportunity costs, but the mindset in North Korea is different – they don’t think that way.”

Hence, the massive prioritization of arms acquisitions.

“The state is very capable at squeezing resources out of their society and economy,” Pinkston said. “They see this as necessary in a menacing world that is ‘out to get’ North Korea.”

Go believes that Pyongyang may try to leverage military strength to extract economic concessions from Japan and South Korea. But Pinkston cautions against any likelihood of denuclearization.

“From North Korea’s perspective, you can never have enough power,” he said. “Trading weapons for some kind of security assurance contradicts their world view.”

This turns the acquisition of an advanced armory into an endless end game – one that does not aid their civil economy.

“They live in this echo chamber that reconfirms their prior beliefs, it reinforces itself,” Pinkston, who reads North Korean state media material in Korean, insisted. “But what are you going to do with a nuclear weapon? You can’t eat plutonium.”

Actual nuclear use would be “suicide” for such a small state, Pinkston opined. North Korea lacks strategic depth, meaning a single nuclear-armed US B52 bomber or submarine could obliterate the nation.

And just as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine invigorated his personal bugbear, North Korea’s actions are generating regional blowback.

“Putin was paranoid about NATO coming after him, but in the past year he has done more to strengthen NATO unity than anyone,” said Pinkston. “It’s the same with North Korea and China – international security cooperation is moving forward.”

He cited recent missile defense drills off Hawaii with Japanese, South Korean and US units, as well as the recent – and likely upcoming – trilateral naval drills in the Sea of Japan.

Yet, there could feasibly be a way for North Korea to acquire allies and embed itself into a community of nations.

“North Korea has put all their eggs in the nuclear basket. They did not diversity their national strategy – there is no way out,” Go said. “If it fails, the only Plan B is the division of the world into authoritarian and liberal blocs, which is a potential development.”

But any such global bifurcation cannot be counted upon, Go stressed: “It is only a prospect.”

SEOUL – Japanese and South Korean forces resumed naval exercises today with the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier strike group in the Sea of Japan – exercises moves that are certain to furro…

asiatimes.com