North Korea Is Preparing to Confront the US in 2022

Kim Jong Un will likely conduct more advanced weapons tests this year in his own version of “maximum pressure.”

By

Sang-soo Lee

January 29, 2022

This photo provided by the North Korean government, shows what it says a test launch of a hypersonic missile in North Korea on Jan. 5, 2022.

Credit: Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP, File

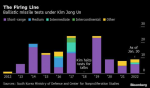

Since Pyongyang rejected the Biden administration’s proposal of diplomatic talks as insufficient to entice Kim Jong Un back to the negotiating table, North Korea seems to have recalibrated its strategy in dealing with the United States. While the North’s end of year report conspicuously condensed the outcome of its review on foreign policy and replaced Kim’s New Year’s Day address, it is expected that North Korea will conduct more advanced weapons tests and hold military parades to draw full attention from the U.S. and the international community in the upcoming months. This can be seen as North Korea’s own style of a “maximum pressure” strategy, meant to change the United States’ fundamental policy toward the country – what Pyongyang calls the “hostile policy” – before restoring the talks.

North Korea’s 2022 Security and Foreign Policy

Despite the 10th anniversary of Kim Jong Un’s ascension to power last year, he did not deliver a New Year’s Day address in 2022. While North Korean state media

reported the results of the five-day plenary meeting of the Workers’ Party Eighth Central Committee on December 27-31, it is puzzling that Pyongyang did not share details on its foreign policy and strategy for 2022.

It just said that the meeting reviewed “principled issues” and relevant strategic directions to cope with the rapidly changing international political situation.

Many experts said the absence of an announcement on North Korea’s foreign policy direction could be seen as providing “strategic flexibility” or room to maneuver in the uncertain external environment. Considering the upcoming events, the Beijing Winter Games in February and the South Korean presidential election in March, there are many uncertainties in the region. The possibility of military conflicts in Ukraine and Taiwan cannot be ruled out this year either. However, those upcoming events will have only a limited impact on determining North Korea’s approach to external affairs. China is likely to turn a blind eye to North Korea’s further missile tests if it stays silent during the Olympics. In addition, whoever the next South Korean president is, the foundation of Seoul’s approach to Pyongyang will not change without Washington’s approval.

As a result, Pyongyang might have already evaluated the impacts of future external affairs and set its direction on the foreign policy by taking a “frontal breakthrough” and “strong to strong” strategy to deal with the U.S. and South Korea. Thus, while it is strategically hidden from public reports, North Korea has already prepared its military action plans, such as a series of future missile and possibly even nuclear tests in response to U.S. sanctions, the upcoming South Korea-U.S. joint military exercises, and the potential victory of South Korean main opposition presidential candidate Yoon Suk-yeol in the election.

https://thediplomat.com/subscriptions/

North Korea has already tested its missile capabilities six times this month, signaling Pyongyang’s clear intention to follow through with Kim’s 2021 pledge of strengthening the national military capability. Pyongyang will continue carrying out more missile tests in the coming months to demonstrate advancements in its missile technologies. Kim believes that maximum pressure by demonstrating powerful nuclear and missile weapons might be the only way to push the U.S. to make concessions.

A Full Speed “Frontal Breakthrough”

Amid the deadlocked nuclear talks and the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, this year is especially important for Kim. He will need to show his strong leadership on the 110th birth anniversary of Kim Il Sung, the country’s founder, and the 80th birth anniversary of Kim Jong Il, Kim’s father, which are coming up in April and February, respectively. At the plenary session in December, Kim mainly focused on delivering his messages on the development of North Korea’s rural and agricultural sector in a bid to revive

his country’s crippled economy, which has been worsened by a brutal combination of U.N.-led economic sanctions, extreme anti-pandemic measures, and natural disasters since early 2020. Kim’s hands, however, are tied as to the economy as there is no long-term plan he can follow to tackle the country’s devastating food shortages without undercutting his self-reliance approach, as aggressive anti-pandemic measures have completely cut North Korea off from the world since early 2020. It is believed that the only long-term solution for the regime to improve its economic situation is reopening the border with China or resuming nuclear negotiations with the U.S. to lift existing sanctions.

Given this situation, after two years of a self-imposed border lockdown, two cargo trains from North Korea

crossed the border from Sinuiju to Dandong on January 16-17 to receive aid and basic necessities from China. Pyongyang might have decided to restart trade with China to recover its economic situation since disinfection facilities have already been installed on the border area. Furthermore, the resumption of aid from China could make it possible for Pyongyang to push forward its maximal nuclear strategy this year, as it will cushion North Korea against the impact of further sanctions. As the hegemonic race between the two superpowers – the United States and China – is most likely to intensify in the future, North Korea will seek more close cooperation with China to revive its economy by resuming trade, while carrying out “tit-for-tat” responses to U.S. sanctions.

Even if Kim needs negotiations to find a long-term solution for North Korea’s economic difficulties, he will continue focusing on building his strong nuclear power at least until the global pandemic crisis is over. The current situation will prevent North Korean officials from meeting foreign delegations either in the country or abroad. Given the circumstances, therefore, this year is a perfect time for the regime to exert maximum pressure on the U.S. to achieve what it wants prior to restoring talks, as the U.S. is now struggling with Russia in Eastern Europe and with China in East Asia.

Showcase of New Advanced Weapons

Starting off with its first hypersonic missile test of the year on January 5, North Korea has conducted six rounds of missile tests, including hypersonic missiles, cruise missiles, and short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMS), this month alone. Among others, the North’s second hypersonic missile test on January 11 proved that it had successfully developed an advanced version of the hypersonic missile it first tested in September of last year. After that, North Korea fired its KN series of SRBMs on January 14 and 18 in the wake of U.S. sanctions over the missile tests. Pyongyang has angrily criticized the U.S. and South Korea for having a “double standard” toward the military activities conducted by the two Koreas. North Korea deems the South Korea-U.S. joint military drills as proof of “hostile intent” that critically threatens the North’s security while reiterating that its missile tests are for its “self-defense,” not for targeting other countries. Pyongyang justifies its missile tests as part of its policy of responding to strength with strength.

As 2022 continues, North Korea will likely show off even more advanced missile weapons in order to fulfil the pledges made during the Eighth Party Congress last year. In this context, North Korea will test new destructive weapons, and they will not be the typical SRBMs the North launched this month. Looking back on the missiles North Korea test-fired before the nuclear talks began in 2018 and the missiles it displayed in a military parade last year, North Korea’s advanced series of “Pukkuksong” missiles are expected to be showcased this year. North Korea will likely test what it has been developing in recent years, including the improved version of its

Pukkuksong-2 solid-fuel ballistic missile and the newest

Pukkuksong-5 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM).

Furthermore, North Korea’s state media recently reported that the country will reconsider Kim’s self-moratorium on testing nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). With this in mind, Pyongyang will also consider proving its strengthened long-range missile capabilities by showing off its

miniaturized and multiple nuclear warheads, if necessary. If all these new missile technologies bear fruit, the U.S. missile defense system will be vulnerable to North Korea’s new intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Prospects for Future Negotiations

https://thediplomat.com/subscriptions/

Back in 2019, Kim

said he no longer felt bound by his self-moratorium on nuclear and ICBM tests while reiterating that he will never come back to the negotiating table unless the U.S. makes concessions. For North Korea, this means lifting the U.S.-led economic sanctions, withdrawing U.S. troops from South Korea, and suspending the joint South Korea-U.S military drills.

In this regard, what the U.S. and South Korea should bear in mind is that it is not the right time to activate their backchannels to restore talks with North Korea and seek a détente. Pyongyang is not ready to return negotiations. Nevertheless, U.S. President Joe Biden must reassess his administration’s strategic patience policy, as just waiting for Pyongyang to return to diplomatic talks runs the risk of North Korea eventually reaching an untouchable level of nuclear capacity. Furthermore, South Korea will also beef up its military capability to deal with nuclear threats from North Korea, in particular as the conservative presidential candidate, Yoon, has claimed the right to conduct a pre-emptive strike on the North. Accordingly, the situation as it stands could push the existing arms race on the Korean Peninsula into a dangerous end game.

The Biden administration has presented an updated nuclear policy that will reduce the importance of nuclear weapons within Washington’s national security strategy. In November 2021, Biden and Xi Jinping agreed during their

virtual summit to launch a series of high-level arms control talks. This shows that the Biden presidency is becoming more and more conscious of the value of arms control agreements in restraining global nuclear arms competition. Biden and Kim might be also interested in the establishment of an arms control framework on the Korean Peninsula – an attractive entry point for future negotiations, which can be the basic foundation of the long-term denuclearization process on the Korean Peninsula. In the long term, Washington might benefit a lot from such a framework. Multilateral nuclear arms control measures could prove a useful tool to reduce the arms race between regional actors – namely North Korea, China, South Korea, and Japan – and control the proliferation of nuclear weapons through the reduction of capabilities and assets in the region.

Authors

Guest Author

Sang-soo Lee

Sang-soo Lee is the deputy director of the Institute for Security & Development Policy (ISDP) and the head of ISDP’s Korea Center.

Kim Jong Un will likely conduct more advanced weapons tests this year in his own version of “maximum pressure.”

thediplomat.com

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/45TRKDVJCFNIPFOIGMDILNKFX4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/7XKGXTLPJFN7LMO6BMTJAG6SYI.jpg)