You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

CRIME 'serious concern' that mother and baby home (unwed mother homes) records will be sealed for 30 years-Ireland

Was digging through the archives chasing twigs on the family tree. 1900 Census. Ran across several pages of children, some with no last name. County orphanage. Kids without last names, young, found on the doorstep in the morning. Mother had died most likely and Pa could not handle them. And they knew only their given name.

Hard times in the Olde Days.

Hard times in the Olde Days.

Melodi

Disaster Cat

They have done some excavations, the number 300 was not taken out of the air, the only question was would the rest of the bones be "covered up" (literally and figuratively) declared consecrated ground by a Priest and then left with a memorial stone or if there would be many years of investigation to find any DNA possible and try to identify each and every bone."...Remember the horribly ugly Irish "Baby and Mother Homes"[Homes for unwed Mothers] in Ireland horror stories a few years ago, you know the one where the only "home" excavated so far found the bodies of dozens, maybe hundreds of dead babies and small children thrown in the sewer? ..."

Seems there is (was?) an eyewitness to maybe 20.

But the number finally bandied about was 300 corpses. Unfortunately, that seems to be a Phact. ( A Phact is what is believed, whether true or not it is believed and therefore is true)

The Government was shocked to the core when their "great solution" was soundly rejected by locals who demanded real DNA be looked for, I haven't heard an update late.

I know that the further excavation of other homes believed to also have dozens to hundreds of tiny bodies, like the one about 7 to 10 miles from my house, simply keeps getting "delayed" with every year a different excuse.

Right now, of course, that excuse is COVID but before that, it was things like "negotiating with the current property owners" or contracting the labor or paperwork delays - again all typically "Orish."

Orish is the local "Irish" term for things that are so stereotypical of what is believed to be true about Ireland or tourist-aimed chestnuts like leprechauns, coffee cups that say "Kiss Me I'm Irish" or drunken playwrights.

The endless delays are very "Orish" in that they are delayed and delayed and delayed by all sorts of excuses in the hope that people will get the message that there are no real plans to do everything and they hope you will all go away now.

This time, it isn't working...

Melodi

Disaster Cat

This photo is from a longer, technical article about the bill which I think most people here would find tedious in the extreme but I will give the link if anyone wishes to go read it.

But I thought this photo, with its number 800 babies would be useful, that's just one home's worth of babies whose remains are believed to have been thrown into the sewer! We are not taking just a few cases here...

A grotto at the unmarked mass grave containing the remains of nearly 800 infants who died at the Bon Secours mother-and-baby home in Tuam.

From:

www.thejournal.ie

www.thejournal.ie

But I thought this photo, with its number 800 babies would be useful, that's just one home's worth of babies whose remains are believed to have been thrown into the sewer! We are not taking just a few cases here...

A grotto at the unmarked mass grave containing the remains of nearly 800 infants who died at the Bon Secours mother-and-baby home in Tuam.

From:

Dr Maeve O'Rourke: Here's a full analysis of the problems with the Government's Mother and Baby Homes Bill

Lecturer Maeve O’Rourke analyses the government’s nine main arguments in relation to the Bill.

Melodi

Disaster Cat

And someone finally just leaked the report to the press, suddenly an official "apology" is coming though I think the former slaves (the courts have ruled they were slaves) would prefer money towards a more comfortable old age, some of these women spent nearly their entire lives working as slaves in the laundries and had their babies stolen and sold for several generations. This isn't going away, and most of the sites have yet to be excavated for bodies of babies like the ones that were thrown into the sewer and not even given a proper burial a the ONE home excavated so far - Melodi

www.rte.ie

Leak of mother-and-baby report 'regrettable' - Taoiseach

www.rte.ie

Leak of mother-and-baby report 'regrettable' - Taoiseach

Updated / Monday, 11 Jan 2021 11:55

The 3,000-page report will be published this week

Taoiseach Micheál Martin has described as regrettable that the Mother and Baby Homes Commission's report was leaked to the Sunday Independent.

Campaigners and opposition politicians have criticised the leaking of the report, saying the publication of sensitive information had caused more pain for survivors.

Speaking on Newstalk, Mr Martin said that the Government response to the report this week would be comprehensive.

The Taoiseach, who will make a State apology later this week, said the "follow through" on the report's recommendations would be "very important".

He said that in the modern era, various Government reports have been leaked, adding that "we will be addressing that issue as well".

Tánaiste Leo Varadkar said the leak was "very, very disrespectful" and that the women who were waiting for the report should have been the first to see it.

Speaking on RTÉ's Today with Claire Byrne, he said the most important thing is to allow the women time to read and digest the report.

He said the report is a difficult one to read, particularly the individual testimonies, and he thanked those who helped prepare it, particularly historian Catherine Corless.

Speaking on the same programme, Ms Corless said: "The leak has broken trust with government again."

Call to delay publication of report

Ms Corless called for the publication of the report to be delayed to allow survivors to have extra time to talk to the Government and to give them a chance to look at the report before it is sent to the media.

She said she hoped the publication of the report would be a great relief but said she was still very apprehensive especially after some of the contents of the report were leaked.

She said it had upset a lot of survivors and a lot of people and she thought it had broken a trust again in the Government, because the one thing that all the groups lobbied for was that they would get information first.

Ms Corless said that survivors should be given time and space to prove that they are important, because they have had live all their lives being treated as second class citizens and this was the one chance to put them to the forefront.

Catherine Corless at the site of the mother-and-baby home in Tuam

Catherine Corless at the site of the mother-and-baby home in Tuam

She said that while she would welcome an apology from the Taoiseach, would there be an apology from the church and the religious institutions as well.

Ms Corless also said she hoped the full truth of all that had happened in all the homes will come out.

The co-founder of the Adoption Rights Alliance has expressed concern at the tone of the coverage of the report.

Susan Lohan said that she is concerned that "the Government is about to trivialise the really big human rights issues" that occurred in the homes when it publishes the commission's report this week.

Speaking on RTÉ's Morning Ireland, Ms Lohan said that she is "really dismayed at the tone of the article" that was published in the Sunday Independent, which contained leaked details of the report.

A member of the Collaborative Forum on Mother and Baby homes, Ms Lohan raised concerns about the newspaper running a side-bar article about women washing floors in the homes.

"I think the tone of the report that we've been given to believe, is one of describing the conditions in the homes, but of course the big question, the elephant in the room, is why were these homes established in the first place," Ms Lohan said.

"For years, survivors groups have been saying that this is a form of social engineering, that the State and church worked in concert to ensure that women, unmarried mothers and girls, who were deemed to be a moral threat to the tone of the country, that they were to be out of public sight, incarcerated ... to ensure that they would not offend public morality."

Ms Lohan said it was to achieve this aim that the children of these women were taken away and given to those of "good" families.

"I'm not hopeful that these big issues are going to be addressed given that in the leak to the Sunday Independent they haven't led with that kind of content," Ms Lohan said.

Taoiseach to give State apology to mother-and-baby home survivors

Ms Lohan said that she believed this week's State apology should be "start in a series of apologies".

She said that survivors would require weeks to analyse the content of this report which runs to more than 3,000 pages.

"How can they possibly adjudicate on the sincerity of a State apology, until they have had weeks ... to digest the full report," Ms Lohan said.

While this report covers 18 home and institutions, Ms Lohan said that 180 places were part of the Ireland's "forced adoption system", including State maternity hospitals.

She said that submissions to include them in the scope of the commission's work had not been accepted.

"The State has not even dealt with its full involvement in this awful industry and the massive human rights abuses that came with it," Ms Lohan said.

Ms Lohan said that "to this day" State agencies such as Tusla were still denying adopted people access to their own personal information, including their birth certificates.

She said they "offended adopted people and those born in mother-and-baby homes" by telling them they have to adjudicate the amount of harm acceding to such requests would cause to other individuals.

Ms Lohan accused Tusla of not being "fit for purpose".

More stories on

Leak of mother-and-baby report 'regrettable' - Martin

Taoiseach Micheál Martin has described as regrettable that the Mother and Baby Homes Commission's report was leaked to the Sunday Independent.

Updated / Monday, 11 Jan 2021 11:55

The 3,000-page report will be published this week

Taoiseach Micheál Martin has described as regrettable that the Mother and Baby Homes Commission's report was leaked to the Sunday Independent.

Campaigners and opposition politicians have criticised the leaking of the report, saying the publication of sensitive information had caused more pain for survivors.

Speaking on Newstalk, Mr Martin said that the Government response to the report this week would be comprehensive.

The Taoiseach, who will make a State apology later this week, said the "follow through" on the report's recommendations would be "very important".

He said that in the modern era, various Government reports have been leaked, adding that "we will be addressing that issue as well".

Tánaiste Leo Varadkar said the leak was "very, very disrespectful" and that the women who were waiting for the report should have been the first to see it.

Speaking on RTÉ's Today with Claire Byrne, he said the most important thing is to allow the women time to read and digest the report.

He said the report is a difficult one to read, particularly the individual testimonies, and he thanked those who helped prepare it, particularly historian Catherine Corless.

Speaking on the same programme, Ms Corless said: "The leak has broken trust with government again."

Call to delay publication of report

Ms Corless called for the publication of the report to be delayed to allow survivors to have extra time to talk to the Government and to give them a chance to look at the report before it is sent to the media.

She said she hoped the publication of the report would be a great relief but said she was still very apprehensive especially after some of the contents of the report were leaked.

She said it had upset a lot of survivors and a lot of people and she thought it had broken a trust again in the Government, because the one thing that all the groups lobbied for was that they would get information first.

Ms Corless said that survivors should be given time and space to prove that they are important, because they have had live all their lives being treated as second class citizens and this was the one chance to put them to the forefront.

She said that while she would welcome an apology from the Taoiseach, would there be an apology from the church and the religious institutions as well.

Ms Corless also said she hoped the full truth of all that had happened in all the homes will come out.

The co-founder of the Adoption Rights Alliance has expressed concern at the tone of the coverage of the report.

Susan Lohan said that she is concerned that "the Government is about to trivialise the really big human rights issues" that occurred in the homes when it publishes the commission's report this week.

Speaking on RTÉ's Morning Ireland, Ms Lohan said that she is "really dismayed at the tone of the article" that was published in the Sunday Independent, which contained leaked details of the report.

A member of the Collaborative Forum on Mother and Baby homes, Ms Lohan raised concerns about the newspaper running a side-bar article about women washing floors in the homes.

"I think the tone of the report that we've been given to believe, is one of describing the conditions in the homes, but of course the big question, the elephant in the room, is why were these homes established in the first place," Ms Lohan said.

"For years, survivors groups have been saying that this is a form of social engineering, that the State and church worked in concert to ensure that women, unmarried mothers and girls, who were deemed to be a moral threat to the tone of the country, that they were to be out of public sight, incarcerated ... to ensure that they would not offend public morality."

Ms Lohan said it was to achieve this aim that the children of these women were taken away and given to those of "good" families.

"I'm not hopeful that these big issues are going to be addressed given that in the leak to the Sunday Independent they haven't led with that kind of content," Ms Lohan said.

Taoiseach to give State apology to mother-and-baby home survivors

Ms Lohan said that she believed this week's State apology should be "start in a series of apologies".

She said that survivors would require weeks to analyse the content of this report which runs to more than 3,000 pages.

"How can they possibly adjudicate on the sincerity of a State apology, until they have had weeks ... to digest the full report," Ms Lohan said.

While this report covers 18 home and institutions, Ms Lohan said that 180 places were part of the Ireland's "forced adoption system", including State maternity hospitals.

She said that submissions to include them in the scope of the commission's work had not been accepted.

"The State has not even dealt with its full involvement in this awful industry and the massive human rights abuses that came with it," Ms Lohan said.

Ms Lohan said that "to this day" State agencies such as Tusla were still denying adopted people access to their own personal information, including their birth certificates.

She said they "offended adopted people and those born in mother-and-baby homes" by telling them they have to adjudicate the amount of harm acceding to such requests would cause to other individuals.

Ms Lohan accused Tusla of not being "fit for purpose".

More stories on

One has to wonder if USSC chief justice roberts was the benefactor of of this child for sale scheme when he "somehow" against Irish law was able to "adopt" two Irish children via a South American "connection" and bypass the "system" ...inquiring minds want to know....

Melodi

Disaster Cat

This is totally possible, however, I have a hunch that if this is what they "have" on him he was probably more involved than just simply the adoption.One has to wonder if USSC chief justice roberts was the benefactor of of this child for sale scheme when he "somehow" against Irish law was able to "adopt" two Irish children via a South American "connection" and bypass the "system" ...inquiring minds want to know....

Most Irish adoptions from the late 1920s through the early 1990s were probably technically illegal but most courts have found the falt to be with the various Agencies, Religious Orders and Churches involved; not with a couple just going to an agency and paying large "fees" for a little extra help with a "private" adoption.

Part of the "Mother and Baby Home" Saga was the wholesale stealing of babies by both Catholic Religious Orders and some Protestant Agencies, and then enslaving the Mothers (sometimes for decades or for life) to work off their "sins" in the Magdalen Laundries.

The courts have ruled these ladies were slaves, they were unpaid and if they rain away the police would take them back; and many had their babies stolen against their wills, others were forced to sign paperwork - there was "no option" to keep the babies.

But these sorts of "operations" especially sending the babies overseas (and most of them went to America or Canada) takes a lot of "cooperation" from legal folks on the ground, I do wonder if Roberts was up to his eyeballs in that one? I guess we may find out eventually if someone decides it is time to be rid of him...

Melodi

Disaster Cat

I knew this was coming and I want to throw up - while better than "800" dead babies, 42 in the nearest real town to us (where we do almost all our shopping and other activities) makes me rather ill. The report was just officially released, I expect the news around the country to get a lot worse over the next few hours At least these babies got a proper burial rather than a sewer - Melodi

www.thejournal.ie

Commission finds remains of at least 42 infants in burial plot of former mother and baby home

www.thejournal.ie

Commission finds remains of at least 42 infants in burial plot of former mother and baby home

6,414 women were admitted to Sean Ross Abbey and 6,079 children were born or admitted there between 1931 and 1969.

10 minutes ago 768 Views 0 Comments

Share Tweet Email

Philomena Lee, who was resident at Sean Ross Abbey in the early 1950, at a private memorial for her son Anthony Lee (Michael Hess) who was lost to her by forced adoption in the mid-1950s.Source: Mark Stedman/Photocall Ireland

Philomena Lee, who was resident at Sean Ross Abbey in the early 1950, at a private memorial for her son Anthony Lee (Michael Hess) who was lost to her by forced adoption in the mid-1950s.Source: Mark Stedman/Photocall Ireland

THE REMAINS OF at least 42 infants buried at the site of the former Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, Co Tipperary have been located as part of the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes.

These remains appear to have been buried in coffins, unlike the situation at Tuam in Co Galway where bodies were found in a chamber of a disused septic tank.

The Commission’s final report, spanning just under 3,000 pages, details the experiences of women and children who lived in 14 mother and baby homes and four county homes – a sample of the overall number of homes – between 1922 and 1998.

It also examines living conditions and mortality among mothers and babies as well as post-mortem practices.

Today’s report confirms that about 9,000 children died in the 18 homes under investigation – about 15% of all the children who were in the institutions.

The report notes: “In the years before 1960 mother and baby homes did not save the lives of ‘illegitimate’ children; in fact, they appear to have significantly reduced their prospects of survival. The very high mortality rates were known to local and national authorities at the time and were recorded in official publications.”

While the Commission found a number of burials at the Sean Ross site “there is very little extra known to [it] about infant burials” at the mother and baby homes examined, it concluded, with the exception of Tuam in Co Galway.

The Mother and Baby Homes in Bessborough, Castlepollard and Sean Ross were owned and run by the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Unlike Pelletstown and Tuam, they were not local authority owned.

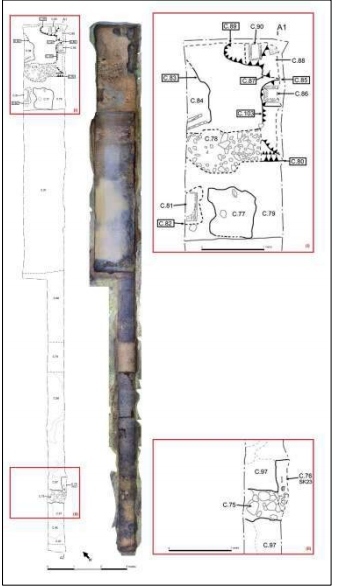

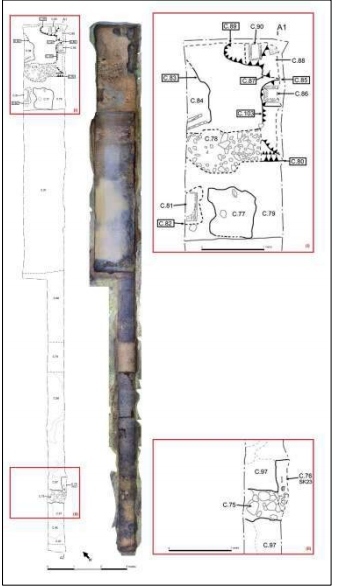

As part of its investigation, the Commission had previously noted that there was a designated burial plot on the grounds of Sean Ross mother and baby home, which opened in 1931 and closed in 1969. As part of its report, 10% of the burial ground was excavated.

Following concerns raised about the burials, the Commission decided to undertake a study and subsequently a test excavation of the site, which was completed in September 2019, to find out if children were buried at the site and if their remains were disturbed by later drainage works.

Seven trenches were opened during the test excavation, representing about 10% of the total available area within the designated burial ground.

Buried infant remains were located during the excavation, the Commission’s report notes. All individuals were less than one year old.

The skeletal remains of 21 individuals were uncovered while the remains of a further 11 coffins, indicating undisturbed burials, were evident.

Four potential grave cuts were also identified and at least six individuals were identified through “disarticulated skeletal remains.”

“Therefore, the potential minimum number of possible individuals identified through the test excavation was 42,” the Commission notes.

Plan drawing of Trench 6 of 7 at Sean Ross burial ground.

Plan drawing of Trench 6 of 7 at Sean Ross burial ground.

The burials at Sean Ross “appear to have some organisation” in terms of layout with coffins or evidence of coffins located with the majority of the remains.

“The logical assumption is that these are intact burials,” according to the archaeological report, which can be read on P. 2,178 of the Commission’s final report.

No coffin or name-plates were identified.

Radiocarbon dating of 13 samples of skeletal remains provided estimated dates of death for those individuals in the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, the time of the operation of the mother and baby home in Sean Ross.

“There can be little doubt that they are the remains of children who died in Sean Ross,” the Commission’s report notes.

“Without complete excavation it is not possible to say conclusively that all of the children who died in Sean Ross are buried in the designated burial ground. The Commission does not consider that further investigation is warranted.”

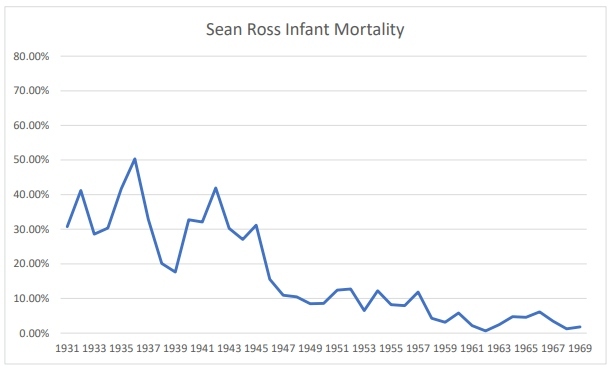

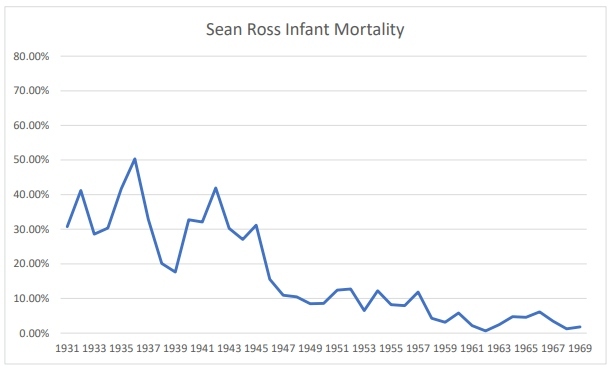

Infant mortality

In its report, the Commission states that 6,414 women were admitted to Sean Ross and 6,079 children were born or admitted there between 1931 and 1969.

It was owned and run by the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary.

The local health board paid for the vast majority of the mothers and their children while they were living in Sean Ross but there were a small number of ‘private’ patients, according to the Commission.

Overcrowding was a serious issue at the home throughout its existence, the Commission’s report shows.

Despite being closed to further admissions in 1945, a further 219 women were admitted that year.

Admissions began to increase from 1961 and 182 women on average were admitted annually in the years 1962-69. Most women sent to Sean Ross were aged between 17 and 30.

The institutional records show that 89.4% of women admitted to Sean Ross stayed and gave birth there.

As part of its work, the Commission identified 37 deaths among women at Sean Ross.

The institutional records show that 1,090 children born in or admitted to Sean Ross died in infancy or early childhood.

“These deaths include children who died in the institution, children who died in hospital following their transfer from Sean Ross and children born to women who had been resident in Sean Ross but gave birth outside the institution,” the Commission notes.

Most infant mortality at Sean Ross occurred between 1932 and 1947.

Of the infant deaths recorded at Sean Ross, over one-third died in infancy. A majority of deaths were medically certified as ‘respiratory infections’, mainly pneumonia, bronchitis and atelectasis.

‘Humiliation and shame’

The Commission received sworn statements from a number of survivors who lived at Sean Ross mother and baby home.

One mother, resident at the home in the early 1950s, became pregnant at 18 and was living with her aunt at the time who, when she found out the woman was pregnant, took her to a doctor who recommended she be admitted to Sean Ross.

#OPEN JOURNALISM No news is bad news Support The Journal

Your contributions will help us continue to deliver the stories that are important to you

SUPPORT US NOW

She was seven months pregnant when she entered the home.

home as “pretty severe but she didn’t receive any punishments”.

She stated that on one occasion she was forced to “go down on my knees” to publicly apologise to a nun. This was “just another part of the humiliation and shame” she was subjected to every day, the Commission’s report notes.

The nuns constantly reminded her that she had “committed a mortal sin” and that “her shame would be eternal”.

The woman was given a ‘house name’ and said there was no doctor present during her labour and no pain relief given.

Her labour was “agonising in accordance with the principle that we had to suffer for our sins,” her testimony states.

She gave birth to a healthy boy and spent eight weeks in the maternity hospital looking after her son and breastfeeding him.

She later signed a consent to adoption form but not was not given time to read the document and “did what she was told”.

Bessborough Burials

In its 3rd interim report, the Commission previously noted that it had difficulties finding out more about the burial arrangements in a number of different institutions due to a lack of burial records.

However, the commission found no physical or documentary evidence of systematic burials in the grounds of Bessborough. It also previously said it did not consider it feasible to excavate the full 60 acres involved, let alone the rest of the 200-acre estate on which there has been extensive building work since the institution closed.

It is still not known where the vast majority of the children who died in Bessborough, Co Cork, run by the same order at Sean Ross, are buried.

More than 900 children died in Bessborough or in hospital after being transferred from Bessborough. Despite very extensive inquiries and searches, the Commission was able to establish the burial place of only 64 children.

In its final report published today, the Commission said “it remains perplexed and concerned at the inability of any member of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary to identify the burial place of the children who died in Bessborough.

“The concern of the congregation about marking the graves of the children who died in Castlepollard does not seem to have applied to the children who died in Bessborough.”

The Commission spent considerable time and resources trying to establish the burial places of more than 1,400 infants and children who died either in Cork County Home/St Finbarr’s Hospital or the Bessborough Home/Sacred Heart Maternity Hospital between 1922 and 1998.

The Commission was able to identify the burial places of 101 infants who died in one or other of these institutions.

“While most burial places were confirmed by an actual burial record (mainly in the 1920s) others were identified through disparate historical sources created by Cork health authorities or hospital personnel,” the Commission states.

“Given the burial practices adopted by maternity hospitals in Cork in the mid to late twentieth century, the Commission considers the task of locating the burial places of the remaining 1,300 plus infants and children who died in Cork County Home/St Finbarr’s Hospital and the Bessborough Home/Sacred Heart Maternity Hospital to be a difficult one.”

Short URL

Commission finds remains of at least 42 infants in burial plot of former mother and baby home

6,414 women were admitted to Sean Ross Abbey and 6,079 children were born or admitted there between 1931 and 1969.

6,414 women were admitted to Sean Ross Abbey and 6,079 children were born or admitted there between 1931 and 1969.

10 minutes ago 768 Views 0 Comments

Share Tweet Email

THE REMAINS OF at least 42 infants buried at the site of the former Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, Co Tipperary have been located as part of the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes.

These remains appear to have been buried in coffins, unlike the situation at Tuam in Co Galway where bodies were found in a chamber of a disused septic tank.

The Commission’s final report, spanning just under 3,000 pages, details the experiences of women and children who lived in 14 mother and baby homes and four county homes – a sample of the overall number of homes – between 1922 and 1998.

It also examines living conditions and mortality among mothers and babies as well as post-mortem practices.

Today’s report confirms that about 9,000 children died in the 18 homes under investigation – about 15% of all the children who were in the institutions.

The report notes: “In the years before 1960 mother and baby homes did not save the lives of ‘illegitimate’ children; in fact, they appear to have significantly reduced their prospects of survival. The very high mortality rates were known to local and national authorities at the time and were recorded in official publications.”

While the Commission found a number of burials at the Sean Ross site “there is very little extra known to [it] about infant burials” at the mother and baby homes examined, it concluded, with the exception of Tuam in Co Galway.

The Mother and Baby Homes in Bessborough, Castlepollard and Sean Ross were owned and run by the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Unlike Pelletstown and Tuam, they were not local authority owned.

As part of its investigation, the Commission had previously noted that there was a designated burial plot on the grounds of Sean Ross mother and baby home, which opened in 1931 and closed in 1969. As part of its report, 10% of the burial ground was excavated.

Following concerns raised about the burials, the Commission decided to undertake a study and subsequently a test excavation of the site, which was completed in September 2019, to find out if children were buried at the site and if their remains were disturbed by later drainage works.

Seven trenches were opened during the test excavation, representing about 10% of the total available area within the designated burial ground.

Buried infant remains were located during the excavation, the Commission’s report notes. All individuals were less than one year old.

The skeletal remains of 21 individuals were uncovered while the remains of a further 11 coffins, indicating undisturbed burials, were evident.

Four potential grave cuts were also identified and at least six individuals were identified through “disarticulated skeletal remains.”

“Therefore, the potential minimum number of possible individuals identified through the test excavation was 42,” the Commission notes.

The burials at Sean Ross “appear to have some organisation” in terms of layout with coffins or evidence of coffins located with the majority of the remains.

“The logical assumption is that these are intact burials,” according to the archaeological report, which can be read on P. 2,178 of the Commission’s final report.

No coffin or name-plates were identified.

Radiocarbon dating of 13 samples of skeletal remains provided estimated dates of death for those individuals in the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, the time of the operation of the mother and baby home in Sean Ross.

“There can be little doubt that they are the remains of children who died in Sean Ross,” the Commission’s report notes.

“Without complete excavation it is not possible to say conclusively that all of the children who died in Sean Ross are buried in the designated burial ground. The Commission does not consider that further investigation is warranted.”

Infant mortality

In its report, the Commission states that 6,414 women were admitted to Sean Ross and 6,079 children were born or admitted there between 1931 and 1969.

It was owned and run by the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary.

The local health board paid for the vast majority of the mothers and their children while they were living in Sean Ross but there were a small number of ‘private’ patients, according to the Commission.

Overcrowding was a serious issue at the home throughout its existence, the Commission’s report shows.

Despite being closed to further admissions in 1945, a further 219 women were admitted that year.

Admissions began to increase from 1961 and 182 women on average were admitted annually in the years 1962-69. Most women sent to Sean Ross were aged between 17 and 30.

The institutional records show that 89.4% of women admitted to Sean Ross stayed and gave birth there.

As part of its work, the Commission identified 37 deaths among women at Sean Ross.

The institutional records show that 1,090 children born in or admitted to Sean Ross died in infancy or early childhood.

“These deaths include children who died in the institution, children who died in hospital following their transfer from Sean Ross and children born to women who had been resident in Sean Ross but gave birth outside the institution,” the Commission notes.

Most infant mortality at Sean Ross occurred between 1932 and 1947.

Of the infant deaths recorded at Sean Ross, over one-third died in infancy. A majority of deaths were medically certified as ‘respiratory infections’, mainly pneumonia, bronchitis and atelectasis.

‘Humiliation and shame’

The Commission received sworn statements from a number of survivors who lived at Sean Ross mother and baby home.

One mother, resident at the home in the early 1950s, became pregnant at 18 and was living with her aunt at the time who, when she found out the woman was pregnant, took her to a doctor who recommended she be admitted to Sean Ross.

#OPEN JOURNALISM No news is bad news Support The Journal

Your contributions will help us continue to deliver the stories that are important to you

SUPPORT US NOW

She was seven months pregnant when she entered the home.

The woman worked at the laundry attached to Sean Ross and described the regime at the home as ”I slept in a large dormitory with other women and girls some of whom were pregnant and others who had already had their babies. Most of my memories have been blocked out over the years but I recall being cold at night and that the clothes they gave us to wear were cold and scratchy. No one had any privacy at all. I cannot remember what the food was like, however, I have an abiding memory of always being hungry.

home as “pretty severe but she didn’t receive any punishments”.

She stated that on one occasion she was forced to “go down on my knees” to publicly apologise to a nun. This was “just another part of the humiliation and shame” she was subjected to every day, the Commission’s report notes.

The nuns constantly reminded her that she had “committed a mortal sin” and that “her shame would be eternal”.

The woman was given a ‘house name’ and said there was no doctor present during her labour and no pain relief given.

Her labour was “agonising in accordance with the principle that we had to suffer for our sins,” her testimony states.

She gave birth to a healthy boy and spent eight weeks in the maternity hospital looking after her son and breastfeeding him.

She later signed a consent to adoption form but not was not given time to read the document and “did what she was told”.

The woman decided that she would try to contact her son in 2003 when she was 70 years old. She contacted Sister Sarto at the former Bessborough mother and baby home in Cork who told her that her son had been adopted in America but had since died.When [the baby] was three and a half years old, he was taken away for adoption. I didn’t get the chance to say goodbye but the same kind nun, Sister Annunciata, informed me that he was leaving, and I ran upstairs and looked out of the window and saw him getting into a car. There was no discussion about it in advance and I was given no information afterwards other than that he had gone. Being parted from him broke my heart.

Bessborough Burials

In its 3rd interim report, the Commission previously noted that it had difficulties finding out more about the burial arrangements in a number of different institutions due to a lack of burial records.

However, the commission found no physical or documentary evidence of systematic burials in the grounds of Bessborough. It also previously said it did not consider it feasible to excavate the full 60 acres involved, let alone the rest of the 200-acre estate on which there has been extensive building work since the institution closed.

It is still not known where the vast majority of the children who died in Bessborough, Co Cork, run by the same order at Sean Ross, are buried.

More than 900 children died in Bessborough or in hospital after being transferred from Bessborough. Despite very extensive inquiries and searches, the Commission was able to establish the burial place of only 64 children.

In its final report published today, the Commission said “it remains perplexed and concerned at the inability of any member of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary to identify the burial place of the children who died in Bessborough.

“The concern of the congregation about marking the graves of the children who died in Castlepollard does not seem to have applied to the children who died in Bessborough.”

The Commission spent considerable time and resources trying to establish the burial places of more than 1,400 infants and children who died either in Cork County Home/St Finbarr’s Hospital or the Bessborough Home/Sacred Heart Maternity Hospital between 1922 and 1998.

The Commission was able to identify the burial places of 101 infants who died in one or other of these institutions.

“While most burial places were confirmed by an actual burial record (mainly in the 1920s) others were identified through disparate historical sources created by Cork health authorities or hospital personnel,” the Commission states.

“Given the burial practices adopted by maternity hospitals in Cork in the mid to late twentieth century, the Commission considers the task of locating the burial places of the remaining 1,300 plus infants and children who died in Cork County Home/St Finbarr’s Hospital and the Bessborough Home/Sacred Heart Maternity Hospital to be a difficult one.”

Short URL

Melodi

Disaster Cat

What happens when a poor country turns all their social services over to "The Church" (whatever religion that may be) with absolutely NO oversight and the full backing of that State - one of the only serious changes made to the modern Irish Constitution from the American was, was to sump the separation of Church and State (now restored and you can see why) don't read this while eating...- Melodi

www.thejournal.ie

'On admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut. She was told: "You're here for your sins"'

www.thejournal.ie

'On admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut. She was told: "You're here for your sins"'

The first-hand testimony from those who were sent to mother and baby homes are included in today’s landmark report.

41 minutes ago 6,718 Views 18 Comments

Share5 Tweet Email2

The key recommendations from today’s report include a State apology, redress and that access to their birth information should be given to survivors of mother and baby homes.

The commission discovered that about 9,000 children died in the 18 homes under investigation: slightly over one in every seven children who were in the institutions.

Flowers and tributes at the site of the former Bon Secours mother and baby home in Tuam, Galway.Source: Laura Hutton/Rollingnews.ie

Flowers and tributes at the site of the former Bon Secours mother and baby home in Tuam, Galway.Source: Laura Hutton/Rollingnews.ie

For almost 180 pages towards the end of the mammoth 2,800 page report, it details the direct testimony of the witnesses themselves who were sent to live in these homes.

The frequently harrowing testimony stretches across seven decades and covers how the women were admitted to a home, the conditions in the homes, the experience of giving birth, growing up in the homes, having children put up for adoption, and the experiences of trying to trace family members in the years that followed.

Here’s what the survivors had to say about their experiences.

Source: DCEDIY/YouTube

Circumstances of pregnancy and admission

The witness testimony is broken down into a number of segments. The first is the circumstances of their pregnancy and admission to a mother and baby home.

Here is some testimony included from the 1950s:

“Three generations, three single mothers – it was in the mid-1950s that a witness, born in a mother and baby home, was later told by her mother that she had become pregnant having been raped by a priest. She said to the Committee that her own mother, the witness’s grandmother, had also been born to an ‘unmarried mother’.

“When she was just 15 years old, this next witness told the Committee, she was returning home from a funfair when ‘a boy of 17 or 18 years old grabbed me and had sex with me’. She said she had thought this was like ‘kiss and chase’ and didn’t question it at the time as ‘that happened regularly to lots of other girls’.

“In school, however, the nun ‘noticed’ her, called her mother in and she was taken to see a doctor, having ‘no idea’ for what reason – and not being privy to the conversation, didn’t realise that the doctor’s verdict was that she was seven months’ pregnant. When this was repeated to her, the witness told the Committee she didn’t understand what that meant – and when it was explained, she could not figure out how it had happened.

“She told the Committee that she did suspect at the time that ‘what I was doing with my boyfriend wasn’t right’. She split up with this boyfriend and returned home but when she told her mother about her condition, ‘my bag was packed and I was run out of the house’. She went back to the UK but a priest ‘became involved’ and the witness was returned to Ireland. A nun collected her at a railway station to escort her to a mother and baby home, where, she said, on admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut, and she was told: ‘You’re here for your sins’.

“A witness who went into a Home in 1964 at the age of 23, told the Committee that she had been abused by her father for many years after her mother had died. She then met a boy, and thought if she could have a baby with someone, she ‘would have her own life’.

“However, when her father discovered she was pregnant, he gave her ‘the hiding of her life’, wrapped cardboard around her stomach and forbade her to be ‘seen outside’. A local priest made arrangements with this father for his daughter to go into the mother and baby home.

“When another witness, 19 years old, became pregnant within a relationship, she told her mother and stepfather – the latter having an ‘important’ job. His reaction was that she ‘needed to get rid of the baby as it might ruin his career’. The reaction of the boyfriend, father of the baby, was one of distress – not for his girlfriend but for his own mother as she was a widow and this ‘would break her heart’.

“When the witness gave birth to her son, he was taken for adoption and her mother collected her from the mother and baby home, took her to the airport to go to an aunt and uncle in the UK, and warned her, ‘not to come back’.

“Then there was a witness who, at the age of 16, had been in a relationship with the birth father for a year discovered that she was pregnant only when she was seven months into it. She told her boyfriend, who told his mother, who was friendly with the local priest.

“‘Nobody will want you now!’ Said by the mother of a witness, 14 years old when her sister ‘informed’ on her, having noticed she was pregnant. The witness was then kept out of sight upstairs.

“A 28-year old woman, separated from her husband and living with her four-year-old child in her parents’ home, dated a man for one night and became pregnant. Her parents were ‘very ashamed’ when they found out – and called a priest. The priest, she told the Committee, ‘then forced her to swear an affidavit’ that the child was not her husband’s.

“She was kept at home, hidden away and forbidden to speak, even to her child; she was not allowed to reply if the child spoke to her. Concerned about their reputation for respectability, her parents were afraid that neighbours might hear her voice and she was kept in hiding until she was eight months’ pregnant, then transferred to a home.

'On admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut. She was told: "You're here for your sins"'

The first-hand testimony from those who were sent to mother and baby homes are included in today’s landmark report.

The first-hand testimony from those who were sent to mother and baby homes are included in today’s landmark report.

41 minutes ago 6,718 Views 18 Comments

Share5 Tweet Email2

‘I was told by a nun: “God doesn’t want you… You’re dirt.”‘

“You could almost feel the tears in the walls.”

THE ABOVE ARE just three of the hundreds of accounts from survivors in the long-awaited final report of the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation.“Her mother called her a ‘prostitute and a whore’. Three of her uncles were priests and her parents were worried about how her pregnancy would affect them.”

The key recommendations from today’s report include a State apology, redress and that access to their birth information should be given to survivors of mother and baby homes.

The commission discovered that about 9,000 children died in the 18 homes under investigation: slightly over one in every seven children who were in the institutions.

For almost 180 pages towards the end of the mammoth 2,800 page report, it details the direct testimony of the witnesses themselves who were sent to live in these homes.

The frequently harrowing testimony stretches across seven decades and covers how the women were admitted to a home, the conditions in the homes, the experience of giving birth, growing up in the homes, having children put up for adoption, and the experiences of trying to trace family members in the years that followed.

Here’s what the survivors had to say about their experiences.

Source: DCEDIY/YouTube

Circumstances of pregnancy and admission

The witness testimony is broken down into a number of segments. The first is the circumstances of their pregnancy and admission to a mother and baby home.

Here is some testimony included from the 1950s:

“Three generations, three single mothers – it was in the mid-1950s that a witness, born in a mother and baby home, was later told by her mother that she had become pregnant having been raped by a priest. She said to the Committee that her own mother, the witness’s grandmother, had also been born to an ‘unmarried mother’.

“When she was just 15 years old, this next witness told the Committee, she was returning home from a funfair when ‘a boy of 17 or 18 years old grabbed me and had sex with me’. She said she had thought this was like ‘kiss and chase’ and didn’t question it at the time as ‘that happened regularly to lots of other girls’.

“In school, however, the nun ‘noticed’ her, called her mother in and she was taken to see a doctor, having ‘no idea’ for what reason – and not being privy to the conversation, didn’t realise that the doctor’s verdict was that she was seven months’ pregnant. When this was repeated to her, the witness told the Committee she didn’t understand what that meant – and when it was explained, she could not figure out how it had happened.

Further account from the 1960s:But soon, the parish priest was called to the house and after his visit, the witness was ‘bundled’ into the van of a local man who drove her, with her father, straight to the mother and baby home. (She had an aunt who was a nun and now believes that this nun had been involved in the arrangements.) All she knew, she said to the Committee, was that she had been ‘plucked’ out of her family and had never returned. ‘Whenever I would come back to Ireland from the UK, I wasn’t allowed to return home. I couldn’t be seen’.

“She told the Committee that she did suspect at the time that ‘what I was doing with my boyfriend wasn’t right’. She split up with this boyfriend and returned home but when she told her mother about her condition, ‘my bag was packed and I was run out of the house’. She went back to the UK but a priest ‘became involved’ and the witness was returned to Ireland. A nun collected her at a railway station to escort her to a mother and baby home, where, she said, on admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut, and she was told: ‘You’re here for your sins’.

“A witness who went into a Home in 1964 at the age of 23, told the Committee that she had been abused by her father for many years after her mother had died. She then met a boy, and thought if she could have a baby with someone, she ‘would have her own life’.

“However, when her father discovered she was pregnant, he gave her ‘the hiding of her life’, wrapped cardboard around her stomach and forbade her to be ‘seen outside’. A local priest made arrangements with this father for his daughter to go into the mother and baby home.

“When another witness, 19 years old, became pregnant within a relationship, she told her mother and stepfather – the latter having an ‘important’ job. His reaction was that she ‘needed to get rid of the baby as it might ruin his career’. The reaction of the boyfriend, father of the baby, was one of distress – not for his girlfriend but for his own mother as she was a widow and this ‘would break her heart’.

“When the witness gave birth to her son, he was taken for adoption and her mother collected her from the mother and baby home, took her to the airport to go to an aunt and uncle in the UK, and warned her, ‘not to come back’.

“Then there was a witness who, at the age of 16, had been in a relationship with the birth father for a year discovered that she was pregnant only when she was seven months into it. She told her boyfriend, who told his mother, who was friendly with the local priest.

Both sets of parents, with the witness, went together to meet the priest in his house. She told the Committee that he examined her internally, taking 45 minutes about it, saying that he ‘needed to establish whether (she) had been sexually active for a while’ – because if she had, he said, she ‘would not be accepted into a mother and baby home’.

Here are some more accounts from the 1970s:According to this witness, her mother called her ‘a prostitute and a whore’. Three of her uncles were priests and her parents were worried about how her pregnancy would affect them. Both sets of parents were also very concerned, she said, about how ‘an unmarried pregnancy’ would affect the careers of the witness’s brothers: ‘Everyone was being thought of but me’.

“‘Nobody will want you now!’ Said by the mother of a witness, 14 years old when her sister ‘informed’ on her, having noticed she was pregnant. The witness was then kept out of sight upstairs.

“A 28-year old woman, separated from her husband and living with her four-year-old child in her parents’ home, dated a man for one night and became pregnant. Her parents were ‘very ashamed’ when they found out – and called a priest. The priest, she told the Committee, ‘then forced her to swear an affidavit’ that the child was not her husband’s.

“She was kept at home, hidden away and forbidden to speak, even to her child; she was not allowed to reply if the child spoke to her. Concerned about their reputation for respectability, her parents were afraid that neighbours might hear her voice and she was kept in hiding until she was eight months’ pregnant, then transferred to a home.

“Brought to hospital after an accident, an 18-year old was discovered to be pregnant. She had been in a relationship with a man, who had left for work abroad. Her mother was informed of this unexpected development and contacted a priest, who from then on, visited the witness regularly in hospital, telling her she had to have the baby adopted to ‘avoid causing embarrassment’ to her family.Real terror was felt by young women when they discovered they were pregnant ‘out of wedlock’. For instance this 17-year-old who had ‘no knowledge of sex,’ feared that her boyfriend ‘would lose interest in her if she didn’t give him what he wanted’, had sex with him and finding she was pregnant, told the Committee that her first thought was: ‘I’ll have to get rid of it’. To that end, in the hope that she would miscarry, she took hot baths and when that didn’t work, threw herself down the stairs of a department store, which didn’t work either. She confided in her mother, and was told she could no longer stay in the family home and she was sent to a mother and baby home.

part 1She told the Committee she believes it was this priest who arranged, with her mother, for her to be taken by ambulance directly from this hospital where she was being treated for her injuries, to a mother and baby home and when she arrived, she was physically examined by two members of staff ‘to check for diseases: girls like you could have anything’.

Melodi

Disaster Cat

Part 2

www.thejournal.ie

Some accounts from the 1980s:

www.thejournal.ie

Some accounts from the 1980s:

“In 1985, a girl raised in state care, and now working as a cook in a boarding school, became pregnant after a ‘casual encounter’ with a local man two years older. When she told him, he ordered her ‘to get rid of the baby’. When she wouldn’t agree, she told the Committee, ‘he pushed me down the stairs in the hope I’d miscarry’. She didn’t. She was sacked from her job, and arrangements were made for her to go to a mother and baby home.

“In 1985, when she was 18 years old, a witness became pregnant to an ‘older guy’ in the UK who was a member of the Church of England. Although she was sent to a home (her parents driving her there) they were ‘largely supportive’. Her mother’s initial response was to ‘nearly to fall off her stool’, while her father’s was: ‘Nobody died’.

“But within half an hour of her arrival, a nun who discovered this was to be a mixed religion child, ‘was on her knees to say a decade of the Rosary’.”

Conditions in the homes

The Commission found that the conditions in these homes for those who resided in them could often be harrowing.

Here’s what they said: “Some witnesses described unkindness in mother and baby homes during all decades under review and not just in the early years.

“Some mothers reported having to do physically exhausting work up to the verge of giving birth, or very soon (as little as two or three days) immediately afterwards; one new mother gave an account of being shouted at and taunted while she was cleaning, post-birth stitches bursting, the cold stone of floor and staircase she had already cleaned now flooding with her blood.

Testimony is also broken down by decade. Here’s some of what survivors had to say.

One man, who lived in a mother and baby home from the late 1940s until the age of six, said: “My memories are of my attempts to escape with my pal from the abuse we were suffering – every day we got out of the room, we climbed up, using the big iron gate, on to the big stone wall that surrounded the place, but the drop to the outside was too deep and we knew we would break our legs if we jumped down.

“We would try to get the attention of someone passing outside, but they would ignore us. The caretaker would come with a ladder to bring us down and the nun would come, grab me by my left ear and drag me inside. I was then locked into a dark room for a day, or sometimes two.

“He said that he was ‘always’ hungry and that he suffered very badly on ‘bath night’ (held on one night a week) because ‘they’ would lace the bathwater with Jeyes Fluid, which caused him great pain: ‘My scrotum would be burning’.”

RELATED READS

12.01.215-year investigation finds at least 9,000 children died in Ireland's mother and baby homes

12.01.21'I expect far more empathy from our leaders': Mother and Baby home survivors' letters to Taoiseach

12.01.21'Accept responsibility and we might accept your apology': Survivors brace themselves for mother and baby home report

“A witness told the Committee that when she was born [1950s], her birth mother was told by the nuns that her baby would be ‘taken’ and that she herself could ‘work off her sin for the next three years’.

“The witness learned that her mother’s response to this information was that if that happened she would ‘go to the top of the building with my child and commit suicide’, the response to this being that she was ‘badly’ beaten by one of the nuns. On hearing of this, the witness’s maternal grandmother took the two of them out of the home.

“She told the Committee that she had worked out why the subsequent relationship between herself and her mother did not work out. ‘She had walked into hell, had decided to blame me for her being there, and could not accept me’.

“Another witness [from the 1960s] recalled watching a child being beaten up: ‘The child was kicked, and she fell, and the blood was pouring out of her head; the nun was hitting her, swiping her… she was unconscious and was carried off’. The witness does not remember ever seeing that child again.

The report also notes positives experiences from some survivors of these homes, such as one witness describing “one kind nun” who gave her chocolate bars to give to her child. This nun also “secretly” took a photograph of the woman’s baby, which she still has to this day.

The Birth Experience

This is how the Commission summarised the experiences women had giving birth in these institutions.

“Many also said they faced into labour and giving birth without having any information at all about what faced them. Some, not expecting it, were shocked to discover what labour entailed when it arose; these girls and women, some up to late teens and even beyond into their 20s, came to a home in complete ignorance of the facts of life, even of ‘where and how the baby gets out’.

“Even of those who had known what to expect in terms of the natural process of birth, what was additionally dreadful for them, they said, was the complete absence of pain medication. This, some alleged, had been deliberate since their birth pains were represented by some nuns (and nurses) as ‘punishment’ – retribution by God for becoming pregnant out of wedlock. One interviewee, screaming for relief, said she was told to look at the crucifix on the wall. Pain relief was given in some hospitals and in a few homes.

She said: “I was washing the floor. I had pains. I was told I was having a baby. My waters broke. I thought I had spilled something or I had wet myself. I was brought to a room and I was put in a bed. There was clear glass in the door, I was screaming in pain. I got out of the bed because I was in so much pain but I was told to get back into the bed. The baby was born. The nun told me to give the baby a name and I did. My baby died. I was never told what happened. I was told I was going home and that I wasn’t to talk about it anymore. My mother told me my baby was dead. I don’t know anything after that’.”

“In the 1970s, a 17-year old ‘didn’t know what to do’ when her waters broke. When she started labour, she was told by a nun: ‘This is your punishment. Remember what will happen tonight, never have another baby before marriage’. She was not given any pain relief and was told by the nurse who delivered the baby: ‘That’s the last time you’re going to see him, he’s gone now’.”

Adoption and consent

The report said that a number of people who’d worked in mother and baby homes in a professional capacity in the 1970s and 1980s spoke about the “culture of adoption” prevalent in mother and baby homes.

“They voiced the opinion that this culture was ‘systemic’ and ‘a belief system’, in that adoption was promoted as the ‘better option’ and that in any event, by having come into a mother and baby home in the first place, the expectation was thereby that women would see this ‘better option’ as the only realistic one and therefore would select it,” the report said.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the report said, deciding whether to give their child up for adoption caused them great distress and agony, with some feeling forced into giving them up.

The report said: “This next witness also told the Committee that she couldn’t read or write. She was raised in State care, was assaulted by a priest and having fallen pregnant, she went into a mother and baby home in 1956, to have her daughter. Like others in this sequence, she insisted that to her knowledge, she ‘hadn’t signed any documents’. In any event, she said, during the 12 months she had spent in the home looking after her baby, ‘there had been no talk of adoption’.

“‘Reeling’ is how she described the feelings she had about the entire experience and especially about the way the institution in which she gave birth, dealt with the adoption. Firstly, she was told to dress the baby and did so in clothes her family had crocheted. She was then instructed to go to the bathroom and get herself dressed. When she returned, her baby was gone. She contacted the adoption agency asking if she could take her baby back, and was told it was too late.”

'On admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut. She was told: "You're here for your sins"'

The first-hand testimony from those who were sent to mother and baby homes are included in today’s landmark report.

“In 1985, a girl raised in state care, and now working as a cook in a boarding school, became pregnant after a ‘casual encounter’ with a local man two years older. When she told him, he ordered her ‘to get rid of the baby’. When she wouldn’t agree, she told the Committee, ‘he pushed me down the stairs in the hope I’d miscarry’. She didn’t. She was sacked from her job, and arrangements were made for her to go to a mother and baby home.

“In 1985, when she was 18 years old, a witness became pregnant to an ‘older guy’ in the UK who was a member of the Church of England. Although she was sent to a home (her parents driving her there) they were ‘largely supportive’. Her mother’s initial response was to ‘nearly to fall off her stool’, while her father’s was: ‘Nobody died’.

“But within half an hour of her arrival, a nun who discovered this was to be a mixed religion child, ‘was on her knees to say a decade of the Rosary’.”

Conditions in the homes

The Commission found that the conditions in these homes for those who resided in them could often be harrowing.

Here’s what they said: “Some witnesses described unkindness in mother and baby homes during all decades under review and not just in the early years.

“Some mothers reported having to do physically exhausting work up to the verge of giving birth, or very soon (as little as two or three days) immediately afterwards; one new mother gave an account of being shouted at and taunted while she was cleaning, post-birth stitches bursting, the cold stone of floor and staircase she had already cleaned now flooding with her blood.

“Some witnesses described that while working on their hands and knees, they were verbally abused about their status as ‘fallen women’. Witnesses reported being called ‘sinners’, ‘dirt’, ‘spawn of Satan’ or worse. They related similar, sometimes identical stories from time spent in institutions where the type of work and living conditions, although based throughout the country in widely spaced geographical locations, seemed to be the same.”Some referenced scrubbing as an inescapable part of their lives in the homes – saying that, while working, they were frequently and very closely supervised by a nun, some of whom would slap or punch them if they were judged not to be working hard or fast enough. Several witnesses from separate mother and baby homes told the Committee that the nun would deliberately ‘re-dirty’ the cleaned surfaces. One related how she had just finished mopping a long corridor when the nun upended her bucket of dirty water and ordered: ‘now clean it again!

Testimony is also broken down by decade. Here’s some of what survivors had to say.

One man, who lived in a mother and baby home from the late 1940s until the age of six, said: “My memories are of my attempts to escape with my pal from the abuse we were suffering – every day we got out of the room, we climbed up, using the big iron gate, on to the big stone wall that surrounded the place, but the drop to the outside was too deep and we knew we would break our legs if we jumped down.

“We would try to get the attention of someone passing outside, but they would ignore us. The caretaker would come with a ladder to bring us down and the nun would come, grab me by my left ear and drag me inside. I was then locked into a dark room for a day, or sometimes two.

I was never sent to school. I used to wet the bed at night, and every morning, the nun would hit me before she grabbed my left ear and dragged me to the wash basins. Sometimes I would trip and fall but she would continue to drag me by the ear. Doctors told me that my ear suffered permanent damage. If I get a cold I lose my hearing in my left ear.

Here, the experience of another man is described: “There was no sense in the home, he went on, of being ‘wanted’ because ‘you were the product of an evil union and being made suffer for the sins of your parents.’ He recounted the backs of his hands being hit with sticks and that the main sustenance for children was ‘goody’, a blend of hot milk, bread and sugar, which could cause severe diarrhoea.I still have nightmares about the place and I wonder how they could be so cruel to little children in a religious country. I sometimes wake and think I’m back there.

“He said that he was ‘always’ hungry and that he suffered very badly on ‘bath night’ (held on one night a week) because ‘they’ would lace the bathwater with Jeyes Fluid, which caused him great pain: ‘My scrotum would be burning’.”

RELATED READS

12.01.215-year investigation finds at least 9,000 children died in Ireland's mother and baby homes

12.01.21'I expect far more empathy from our leaders': Mother and Baby home survivors' letters to Taoiseach

12.01.21'Accept responsibility and we might accept your apology': Survivors brace themselves for mother and baby home report

“A witness told the Committee that when she was born [1950s], her birth mother was told by the nuns that her baby would be ‘taken’ and that she herself could ‘work off her sin for the next three years’.

“The witness learned that her mother’s response to this information was that if that happened she would ‘go to the top of the building with my child and commit suicide’, the response to this being that she was ‘badly’ beaten by one of the nuns. On hearing of this, the witness’s maternal grandmother took the two of them out of the home.

“She told the Committee that she had worked out why the subsequent relationship between herself and her mother did not work out. ‘She had walked into hell, had decided to blame me for her being there, and could not accept me’.

“Another witness [from the 1960s] recalled watching a child being beaten up: ‘The child was kicked, and she fell, and the blood was pouring out of her head; the nun was hitting her, swiping her… she was unconscious and was carried off’. The witness does not remember ever seeing that child again.

The report also includes brief snippet of quotes from survivors: ‘It was clear that we were there to suffer’. ‘My mother came in to see the baby and one of the nuns asked her: ‘Why would you want to see something like that?’ I was told by a nun: ‘God doesn’t want you… ‘You’re dirt’. ‘You could almost feel the tears in the walls’.‘The deaths of babies were covered up’, said some witnesses, with mothers being told, ‘it’s taken care of’. One witness who reported this to the Confidential Committee also said: ‘Mothers were not told where the baby was, or given any records. One young girl whose baby died at two months old wanted to see where her child was buried and was told by the nuns that ‘she shouldn’t know’.

The report also notes positives experiences from some survivors of these homes, such as one witness describing “one kind nun” who gave her chocolate bars to give to her child. This nun also “secretly” took a photograph of the woman’s baby, which she still has to this day.

The Birth Experience

This is how the Commission summarised the experiences women had giving birth in these institutions.

“Many also said they faced into labour and giving birth without having any information at all about what faced them. Some, not expecting it, were shocked to discover what labour entailed when it arose; these girls and women, some up to late teens and even beyond into their 20s, came to a home in complete ignorance of the facts of life, even of ‘where and how the baby gets out’.

“Even of those who had known what to expect in terms of the natural process of birth, what was additionally dreadful for them, they said, was the complete absence of pain medication. This, some alleged, had been deliberate since their birth pains were represented by some nuns (and nurses) as ‘punishment’ – retribution by God for becoming pregnant out of wedlock. One interviewee, screaming for relief, said she was told to look at the crucifix on the wall. Pain relief was given in some hospitals and in a few homes.

‘I never saw a doctor’ was a constant refrain, as was another about not being given time properly to recover from the physical and emotional stress of birth, let alone a very difficult one – or the experience of having your baby ‘whipped away’ without giving you, as a new mother, a chance even to see, touch or hold him or her. Instead, very many said, they were quickly put back to work, some of it exceptionally heavy, as in scrubbing stone floors on hands and knees, or working on the land, and being verbally abused while at it.

Here’s one first-hand account from a woman who was raped at the age of 12 by a family member and became pregnant. She was sent to a mother and baby home.Those whose babies had been bound for adoption right from the start told the Committee how frustrating it was to be forbidden to cuddle or even hold their new babies, even when feeding them in a nursery specifically designated for babies going to new mothers and fathers.

She said: “I was washing the floor. I had pains. I was told I was having a baby. My waters broke. I thought I had spilled something or I had wet myself. I was brought to a room and I was put in a bed. There was clear glass in the door, I was screaming in pain. I got out of the bed because I was in so much pain but I was told to get back into the bed. The baby was born. The nun told me to give the baby a name and I did. My baby died. I was never told what happened. I was told I was going home and that I wasn’t to talk about it anymore. My mother told me my baby was dead. I don’t know anything after that’.”

“In the 1970s, a 17-year old ‘didn’t know what to do’ when her waters broke. When she started labour, she was told by a nun: ‘This is your punishment. Remember what will happen tonight, never have another baby before marriage’. She was not given any pain relief and was told by the nurse who delivered the baby: ‘That’s the last time you’re going to see him, he’s gone now’.”

Adoption and consent

The report said that a number of people who’d worked in mother and baby homes in a professional capacity in the 1970s and 1980s spoke about the “culture of adoption” prevalent in mother and baby homes.

“They voiced the opinion that this culture was ‘systemic’ and ‘a belief system’, in that adoption was promoted as the ‘better option’ and that in any event, by having come into a mother and baby home in the first place, the expectation was thereby that women would see this ‘better option’ as the only realistic one and therefore would select it,” the report said.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the report said, deciding whether to give their child up for adoption caused them great distress and agony, with some feeling forced into giving them up.

The report said: “This next witness also told the Committee that she couldn’t read or write. She was raised in State care, was assaulted by a priest and having fallen pregnant, she went into a mother and baby home in 1956, to have her daughter. Like others in this sequence, she insisted that to her knowledge, she ‘hadn’t signed any documents’. In any event, she said, during the 12 months she had spent in the home looking after her baby, ‘there had been no talk of adoption’.

After that 12 months, she had returned to the institution in which she had been living prior to admission to the home – leaving her daughter behind to be cared for. Later, she got a job, moved into a flat and then went back to the home to collect her daughter. She was not there, and no-one would say where she had gone.

“One witness [in the 1960s], having resisted all pressures and brought her baby home recounted that while walking along a street with the child, both had been ordered into the car of a priest – he had drawn up alongside her, ordered her to get in, and when she did, drove straight to a home. On arrival, she and the baby were separated and the pressure immediately began for her to sign adoption papers. The witness was locked into a room and told she would stay there until she signed the adoption papers for her baby.The witness then went to the adoption agency she presumed had been involved in taking her child out of the home, but it claimed to have no record of a relevant adoption. (However, when this daughter traced the witness in later life, it emerged that the witness and her adoptive family had been living relatively close to each other.) This mother went on to have another pregnancy, resulting in twins and they too, were born in a home. When she asked for them, she was told that they, like her daughter ‘were gone’. To her this phraseology meant that they had died at birth. Some years later, these twins traced the witness just as her first child had.

She told the Committee she ‘kicked and kicked’ that door and ‘wouldn’t stop kicking and yelling,’ demanding release, to see her baby, and that her father should be called. She kept it up until eventually the priest arrived back and tried again, through the locked door, to get her to sign papers, even shoving the papers under it, enticing her with a promise she could leave as soon as she signed, then changing tack and calling her a ‘selfish whip! But she continued to yell, protest and clamour for release.

“This next witness [1970s] was extremely distressed during her meeting with the Confidential Committee when relating her experience of having her baby in a home in the mid-1970s at the age of 19, explaining that she had had no other option. She has had no further children because, she said, she was ‘too scared to go through again what she had gone through’ and she had a lot of regrets about the adoption.Eventually her father was summoned and he took her home with her baby. A short time later, she left her child with her mother and father while she went back to work in the UK. Not long afterwards, however, she got a panicked phone call from her parents: this priest had been calling to the house, threatening guardianship proceedings against her. She came home to collect her daughter.

“‘Reeling’ is how she described the feelings she had about the entire experience and especially about the way the institution in which she gave birth, dealt with the adoption. Firstly, she was told to dress the baby and did so in clothes her family had crocheted. She was then instructed to go to the bathroom and get herself dressed. When she returned, her baby was gone. She contacted the adoption agency asking if she could take her baby back, and was told it was too late.”

Melodi

Disaster Cat

'On admission her clothes were removed, her hair was cut. She was told: "You're here for your sins"'

The first-hand testimony from those who were sent to mother and baby homes are included in today’s landmark report.

Exit and aftermath

A number of witnesses described negative experiences with being fostered or “boarded out” from mother and baby homes.

#OPEN JOURNALISM No news is bad news Support The Journal

Your contributions will help us continue to deliver the stories that are important to you

SUPPORT US NOW

The report said: “A 90-year-old man came to speak to the Confidential Committee of having been in State care during much of his childhood. This witness was just a year old when sent to be ‘boarded out’ from the home, to live in the community with a woman who would, under inspection and supervision, look after him as her own and when the time came, send him to school.