(Beyond Pesticides, October 28, 2021) A study published in Frontiers in Environmental Science finds the popular herbicide glyphosate negatively affects microbial communities, indirectly influencing plant, animal, and human health. Exposure to sublethal concentrations of glyphosate shifts...

beyondpesticides.org

Glyphosate Kills Microorganisms Beneficial to Plants, Animals, and Humans

(

Beyond Pesticides, October 28, 2021) A study published in

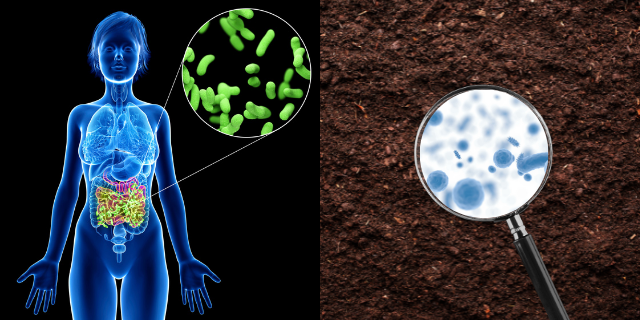

Frontiers in Environmental Science finds the popular herbicide glyphosate negatively affects microbial communities, indirectly influencing plant, animal, and human health. Exposure to sublethal concentrations of glyphosate shifts microbial community composition, destroying beneficial microorganisms while preserving pathogenic organisms.

Glyphosate is the most commonly used active ingredient worldwide, appearing in many herbicide formulas, including Bayer’s (formerly Monsanto) Roundup®. The use of this chemical has been increasing since the inception of crops genetically modified to tolerate glyphosate over two decades ago. The toxic herbicide readily contaminates the ecosystem with residues pervasive in both food and water commodities. In addition to this study, the scientific literature commonly associates glyphosate with human, biotic, and ecosystem

harm, as

a doubling of toxic effects on invertebrates, like pollinators, has been recorded since 2004.

The authors caution, “[O]utbreaks of several animal and plant diseases have been related to glyphosate accumulation in the environment. Long-term glyphosate effects have been underreported, and new standards will be needed for residues in plant and animal products and the environment.” With an increasing number of reports on the relationship between glyphosate and human health, including

potential effects on the human gut microbiome, advocates are calling on global leaders to eliminate chemical use.

The report investigates the indirect impacts that glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) have on plant, animal, and human health. Using the scientific literature, researchers evaluate shifts in microbial community composition among different habitats. These habitats include soils for plants and the gut microbiome for animals and humans. Authors focused on three main issues: the accumulation of glyphosate in the ecosystem (including animal and plant products), the effects the chemical has on microbes in soils, animals, and humans, and whether impacts on microbes induce subsequent adverse effects on plants, animals, and humans.

The report begins with a discussion of glyphosate’s fate in soil and water. The chemical breaks down into its primary metabolite AMPA (aminomethylphosphonic acid) in a matter of a few days. However, clay and organic matter in soils absorb both glyphosate and its metabolite, slowing the breakdown process and making both compounds more ecologically pervasive. Soil type, environmental conditions, and previous exposure of soil microorganisms to glyphosate determine the rate at which the chemical compounds break down. Clay and organic matter in soils do not absorb all chemical constituents, as residues make their way into groundwater during heavy rainfall and contaminate surface water via runoff and erosion. North and South America have the highest concentrations of glyphosate in surface waters. However, rain, treated wastewater, drinking water, and the surrounding air contain glyphosate and AMPA residues.

The authors assess the fate of glyphosate residues on plant and animal products finding the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for these products in 1974. However, the agency recently began incorporating AMPA residues in MRL evaluations for food and feed products from glyphosate biotransformation. Overall, the MRL of glyphosate and AMPA in products differs depending on product type and regulatory practices. In animal feed, MRL levels increase over time to compensate for more pervasive glyphosate use. A Danish study finds chemical concentrations in animal feed are occasionally high enough to cause malformations and infertility among swine, botulism among cows, and pathogenic bacterial disease among chickens.

Furthermore, studies find these farm animals ingesting glyphosate-contaminated fodder excrete the chemical via urine and feces, with up to 96 percent of the compound present in farm animal urine samples. Even among domestic cats and dogs, glyphosate concentrations in urine is relatively high due to high chemical levels in pet food, similar to farm animal fodder. In human urine samples, 90 percent of farmworkers, 60 to 95 percent of the general U.S. population, and 30 percent of newborns have high concentrations of glyphosate.

The report also covers the impact glyphosate has on microbes in soils, animals, and humans. Glyphosate acts on the shikimate pathway, present in plants, fungi, bacteria, archaea, and protozoa. Thus, many taxonomic groups of microorganisms are sensitive to glyphosate. There are two classes of microbial reactions to glyphosate exposure: glyphosate sensitive class I EPSPS and glyphosate-tolerant class II EPSPS. Additionally, classes III and IV include some bacterial and archaeal (single cell organisms that are not bacteria) microbes associated with glyphosate resistance. Class I and II reactions occur more frequently as intensive and chronic pesticide use renders some bacteria and fungi resistant to glyphosate.

These microbes can become resistant by decreasing cell wall permeability or altering the EPSPS enzymatic binding sites. For instance, the study finds glyphosate-resistant bacterial strains like

E. coli and

Pseudomonas alter gene function to enhance the outflow of glyphosate from the bacterial cell. Thus, the authors suggest this resistance mechanism encourages cross-resistance against antibiotics for pathogenic bacterial species like

E. coli and

Salmonella. The authors note that 50 years of extensive glyphosate use also increased human/animal pathogenic bacteria to break down the chemical compound.

Bacillus species like

B. cereus and

B. anthracis can detoxify glyphosate, breaking down the chemical compound. However, the process can increase

B. anthracis (the causative proxy of toxic anthrax) concentrations in the environment over time.

Lastly, the authors review the indirect impacts that glyphosate has on plant, animal, and human health, as these species rely on the diversity and stability of microbial communities. Microorganisms travel through the food chain, interconnecting the health of all organisms. For plants, glyphosate and AMPA indirectly impact plant health through changes in the endophytic and rhizosphere microbiome responsible for plant health and growth, reducing antimicrobial production against pathogens. Furthermore, glyphosate can negatively affect plant nutrient uptake by disrupting microbes that make plant nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, copper, iron, manganese, and zinc available.

Among insects, pollinators like bees can experience severe negative impacts on gut health from glyphosate exposure. The chemical can alter microbes in the gut, resulting in disease outcomes that reduce pollinator fitness. These diseases include deformed wing syndrome (DWS) and increased susceptibility to varroa mites. In humans and animals, a shift in microbial communities within the gut can result in dysbiosis, causing an imbalance between beneficial and pathogenic gut microorganisms. Dysbiosis affects the function of the gastrointestinal tract, limiting the ability to prevent disease and interact with the endocrine (hormone), immune, and nervous system.

Considering pathogenic microbes are less sensitive or insensitive to glyphosate, these disease-causing microbes can accumulate to worsen adverse health effects. Furthermore, the authors note a connection between gut health and neurological diseases as individuals exposed to glyphosate also experience a higher incidence of ADD/ADHD, autism, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s.

Glyphosate has been the

subject of extensive controversy about its safety for humans, non-human organisms, and ecosystems.

Beyond Pesticides has reported on EPA’s ongoing failures to protect people and the environment from GBH compounds. Evidence includes the fact that the presence of glyphosate in human bodies has risen dramatically during the past three decades.

Research out of the University of California San Diego found that, between two data collection periods (1993–1996 and 2014–2016), the percentage of people testing positive for the presence of glyphosate (or its metabolites) in their urine rose by 500 percent, and levels of the compound spiked by 1,208 percent. Furthermore, Bayer/Monsanto controls an extraordinarily high market percentage of seeds genetically engineered (GE) to tolerate glyphosate for corn, soy, and cotton. As of 2018,

more than 90% of these crops in the U.S. are from GE seeds. All those seeds require the use of the GBH herbicide, Roundup. Science and environmental advocates have noted

the multiple risks that glyphosate use represents, with

Beyond Pesticides listing glyphosate as having endocrine, reproductive, neurotoxic, hepatic, renal, developmental, and carcinogenic effects on human health.

Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in lifelong digestion, immune, and central nervous system regulation, as wells as other bodily functions. Through the gut biome, pesticide exposure can enhance or exacerbate the adverse effects of additional environmental toxicants on the body. Since the gut microbiome shapes metabolism, it can mediate some toxic effects of environmental chemicals. However, with prolonged exposure to various environmental contaminants, critical chemical-induced changes may occur in the gut microbes, influencing adverse health outcomes.

Similar to gut microbes, soil microbiota are essential for the normal functionality of the soil ecosystem. Toxic chemicals

damage the soil microbiota by decreasing and altering microbial biomass and soil microbiome composition (diversity). Pesticide use contaminates soil and results in a bacteria-dominant ecosystem as these chemicals cause

“vacant ecological niches, so organisms that were rare become abundant and vice versa.” The bacteria outcompete beneficial fungi, which improves soil productivity and increases carbon sequestration capacity. The resulting soil ecosystem is unhealthy and imbalanced, with a reduction in the natural cycling of nutrients and resilience. Thus, plants grown in such conditions are more

vulnerable to parasites and pathogens. The

effects of climate change only exacerbate threats on soil health as studies show a link between global climate change and a high loss of microbial organisms in the soil ecosystem.

Not only do health officials warn that continuous use of glyphosate will perpetuate adverse health and environmental effects, but that use also highlights recent concerns over

antibiotic resistance. Bayer/Monsanto patents glyphosate as an antibiotic since exposure hinders enzymatic pathways in many bacteria and parasites, serving as an antimicrobial. However, glyphosate kills bacterial species beneficial to humans and incorporated in probiotics yet allows

harmful bacteria to persist, leading to resistance.

Similarly, glyphosate-exposed

soils contain a greater abundance of genes associated with antibiotic resistance, as well as a higher number of inter-species transferable genetic material. Therefore, the use of antibiotics like glyphosate allows residues of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria on agricultural lands to move through the environment, contaminate waterways, and ultimately reach consumers in food. Antibiotic resistance can trigger longer-lasting infections, higher medical expenses, the need for more expensive or hazardous medications, and the inability to treat life-threatening illnesses. Resistance to pesticides is also growing at similar rates among GE and non-GE conventionally grown crops. This increase in resistance is evident among

herbicide-tolerant GE crops, including seeds genetically engineered to be

glyphosate-tolerant. Although one stated purpose of GE crops is to reduce pesticide use, an increase in resistance can result in additional pesticide use to compensate.

The report demonstrates that many studies used for regulatory agency assessments focus on glyphosate’s direct impact on ecosystem health. For instance, glyphosate directly affects the shikimate pathway in some bacteria. However, these agencies fail to consider how chemical exposure may indirectly impact plant, animal, and human health through other mechanisms. In this report, glyphosate is resistant to complete environmental degradation. Specific molecular linkages in the compound break down slowly in water, soil, and dead plant material by various microorganisms. However, with glyphosate causing a shift in microbial communities, there may be insufficient or non-beneficial microorganisms available to break down the toxic compound.

The authors recommend regulatory agencies set combined glyphosate and AMPA tolerance levels for products intended for plant, animal, and human consumption. The report concludes, “We recommend additional interdisciplinary research on the associations between low-level chronic glyphosate exposure, distortions in microbial communities at the species level, and the emergence of animal, human, and plant diseases. A potential connection between glyphosate exposure, populations of pks + bacterial species such as

E. coli, and intestinal cancer development needs to be investigated. Connections between glyphosate resistance in bacteria and antibiotic resistance also deserve more attention. As suggested by us earlier, independent and trustworthy research is needed to revisit the tolerance thresholds for glyphosate residues in water, food, and animal feed, taking all possible health risks into account.”

To improve and sustain microbial communities, and thus human, animal, and environmental health, toxic pesticide use must stop. Beyond Pesticides

challenges the registration of chemicals like glyphosate in court due to their impacts on soil, air, water, and our health. While legal battles press on, the agricultural system should eliminate the use of toxic synthetic herbicides to avoid the myriad of problems they cause. Instead, emphasis on converting to

regenerative-organic systems and using

least-toxic pest control to mitigate harmful exposure to pesticides,

restore soil health, and reduce carbon emissions, should be the main focus. Public policy must advance this shift, rather than continue to allow unnecessary reliance on pesticides. Considering

glyphosate levels in the human body decrease by

70% through a one-week switch to an organic diet,

purchasing organic food whenever possible—which never allows glyphosate use—can help curb exposure and resulting adverse health effects.

Learn more about soil microbiota and its importance via Beyond Pesticide’s journal

Pesticides and You. Additionally, learn more about the effects of pesticides on human health by visiting Beyond Pesticides’

Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database. This database supports the clear need for strategic action to shift away from pesticide dependency. Moreover, Beyond Pesticides provides tools, information, and support to take local action: check out our

factsheet on glyphosate/Roundup and our report,

Monsanto’s Roundup (Glyphosate) Exposed. Contact us for help with local efforts and stay informed of developments through our

Daily News Blog and our journal,

Pesticides and You. Additionally, check out

Carey Gillam’s talk on Monsanto’s corruption on glyphosate/Roundup at Beyond Pesticides’ 36th National Pesticide Forum.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source:

Frontiers in Environmental Science