A less detailed article that reflects many of the point

Coronavirus: What can the 'plague village' of Eyam teach us? - BBC News

Coronavirus: What can the 'plague village' of Eyam teach us?

By Greig Watson

BBC News

Published22 April 2020

Share

IMAGE SOURCE,ALAMY

Image caption,

The desperate urge to flee London risked spreading the plague across the country

With coronavirus putting households around the world in lockdown, can the English "plague village" of Eyam, which quarantined itself for more than a year, offer us lessons on how to fight back?

As a nightmare tale from history, Eyam's ordeal takes some surpassing.

When plague arrived in September 1665, rather than flee this wild corner of Derbyshire - and risk spreading the infection - villagers locked themselves away to suffer in isolation. And suffer they did.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

Image caption,

Eyam's story became well known during Victorian times as an example of self-sacrifice

For 14 months pestilence, pitiless and seemingly random, ravaged the village.

Deaths reached six a day, with one woman losing six children and a husband in just over a week. The graveyard was shut and bodies were dragged into fields for burial.

Traditional estimates put the death toll at about 260 - 75% of the population.

But along with gruesome tales of self-sacrifice, Eyam offers more - a unique opportunity to study how epidemics work.

And researchers have been trying to unlock its secrets to help fight disease - including coronavirus.

IMAGE SOURCE,EYAM MUSEUM

Image caption,

With the graveyard shut and funerals banned, the dead had to be dragged into fields for burial

Resident Joan Plant is related to one of Eyam's most celebrated survivors.

She said: "Margaret Blackwell was my nine-times great-aunt.

"According to family legend, while delirious with the plague she went looking for water to relieve her parched throat.

"By mistake she drank a jug of bacon fat. Soon after her fever broke and she made a full recovery."

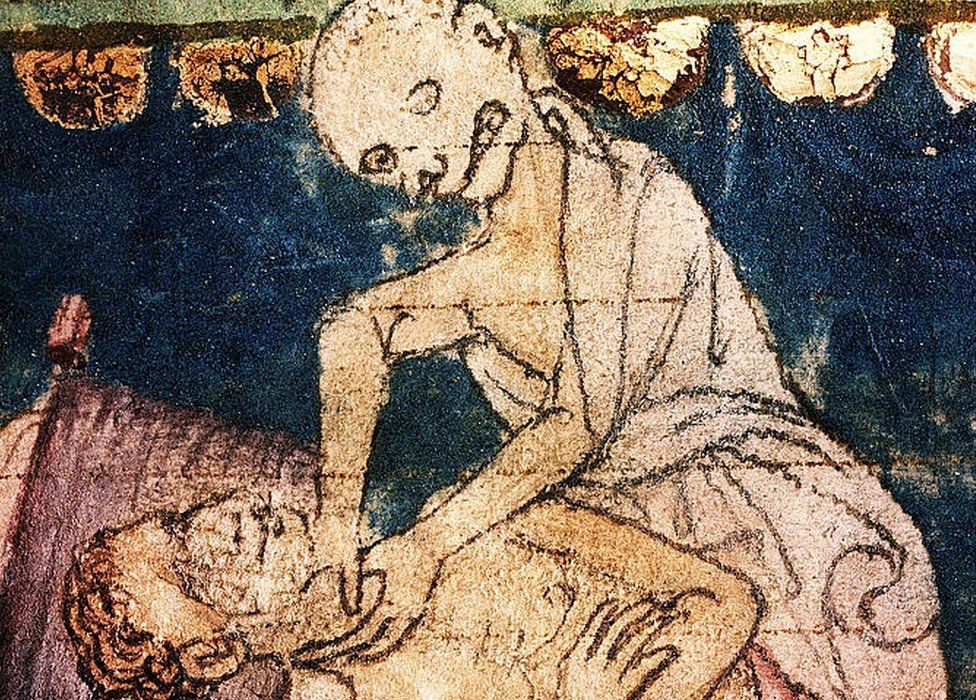

IMAGE SOURCE,HERITAGE IMAGES

Image caption,

The terror of the plague is evoked in this medieval image of death strangling a victim

All this begs lots of questions. Just how lethal was the disease? Why did so many die when families were isolated?

Did drinking bacon fat - or perhaps the instant vomiting this caused - really save Margaret Blackwell?

And perhaps most importantly, did the quarantine save others?

Can 21st Century science answer these questions

and help us learn from the grim fate of one village 350 years ago?

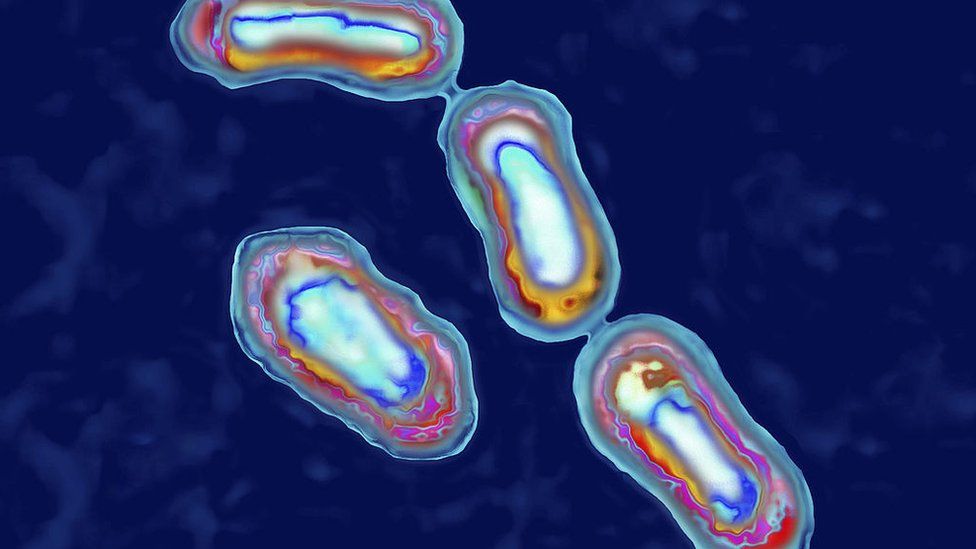

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

Image caption,

The cause of plague - a bacterium called Yersinia pestis - was not discovered until 1894

It is a detective story of controversial ideas, new discoveries and hard lessons for today.

Sheena Cruickshank, professor in biomedical Sciences at the University of Manchester, said: "Learning about our history with disease informs our future.

"We know the immune system combines with other factors - the strength and dose of the pathogen, the health of the individuals, relative isolation - to determine the severity of the epidemic.

"Some factors - living in proximity to animals and affecting animal habitats - still play a role today with diseases like Zika, SARS, and coronavirus being shown to originate in animals "

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

Image caption,

With the arrival of coronavirus, isolation and quarantine have become part of everyday life for many

She added: "While many diagnostic details are missing, Eyam is a snapshot of how one community was shaped by - and itself shaped - the spread of a disease.

"And it is possible that survivors with more effective immunity led to part of the immune system of the survivors being selected for and handed down to following generations.

"As an example, some communities in Africa seem to have a higher incidence of a blood disorder - sickle cell anaemia - because it gave some protection against malaria.

"Reports have also shown that particular immune signatures were associated with more effective immune responses to plague and this can be tracked through generations."

Media caption,

Fergal Keane met people in Eyam, the former 'plague village' in Derbyshire, dealing with coronavirus

In 2000, a team studying natural HIV resistance came to Eyam. They had a remarkable theory that built on the idea of inherited disease resistance.

A human gene mutation, called CCR5-Delta 32, was known to give immunity from HIV.

This mutation seemed to date from just a few hundred years ago and existed almost solely in north European populations and their descendants.

What could have caused it? An epidemic like the plague?

Team leader Dr Steve O'Brien later said: "Could it be that the same mutation that protects against HIV may have also protected medieval Europeans exposed to plague?

"The timing is right, the numbers are right - hundreds of years of unforgiving selective pressure from the sixth to the 18th Centuries would be sufficient to explain today's high CCR5-Δ32 frequency."

/SNIP