Intestinal Fortitude

Have Faith

Another China Cover-Up: Nipah Virus Kills 40%- 70% Infected | Wall Street Rebel

Part of the Wall Street Rebel site. Dedicated to delivering institutional quality market analysis, investor education courses, news, and winning buy/sell recommendations - 100% FREE!

wallstreetrebel.com

Another China Cover-Up: Nipah Virus Kills 40%- 70% Infected

by James DiGeorgia | 03/03/2021 5:10 PM

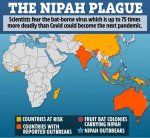

We could be looking at the beginning of another China originating viral plague that’s dramatically more deadly than COVID-19. This nightmare Nipah virus could literally kill billions of people. The Chinese are again suppressing news of this deadly new outbreak, keeping it secret even as it begins shutting down large population and manufacturing centers in China.

The present-day virus that escaped from China in 2019, causing 2,567,358 global deaths and trillions of dollars in economic damage, is just now being beaten back. The approval of the Johnson and Johnson (JNJ: NYSE) Covid-19 Vaccine is a game-changer because it requires only one shot and doesn’t have to be stored in ultra-cold temperatures. President Biden’s invocation of the defense production act marries Johnson and Johnson and Merck & Co., Inc. (MRK: NYSE) that will forge a historic manufacturing collaboration between two of the largest U.S. health care and pharmaceutical companies. That will make it possible to produce enough vaccines in the United States for every adult by the end of May.

Yet, while the end of the pandemic may become a reality, a much more dangerous and deadly virus threat is now on the horizon and, yes, being covered up once again by the Chinese government.

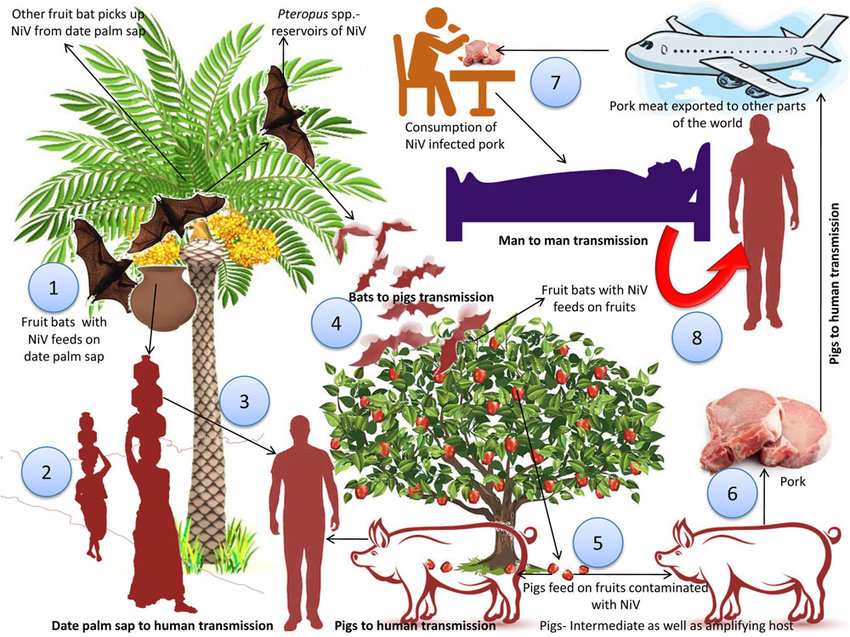

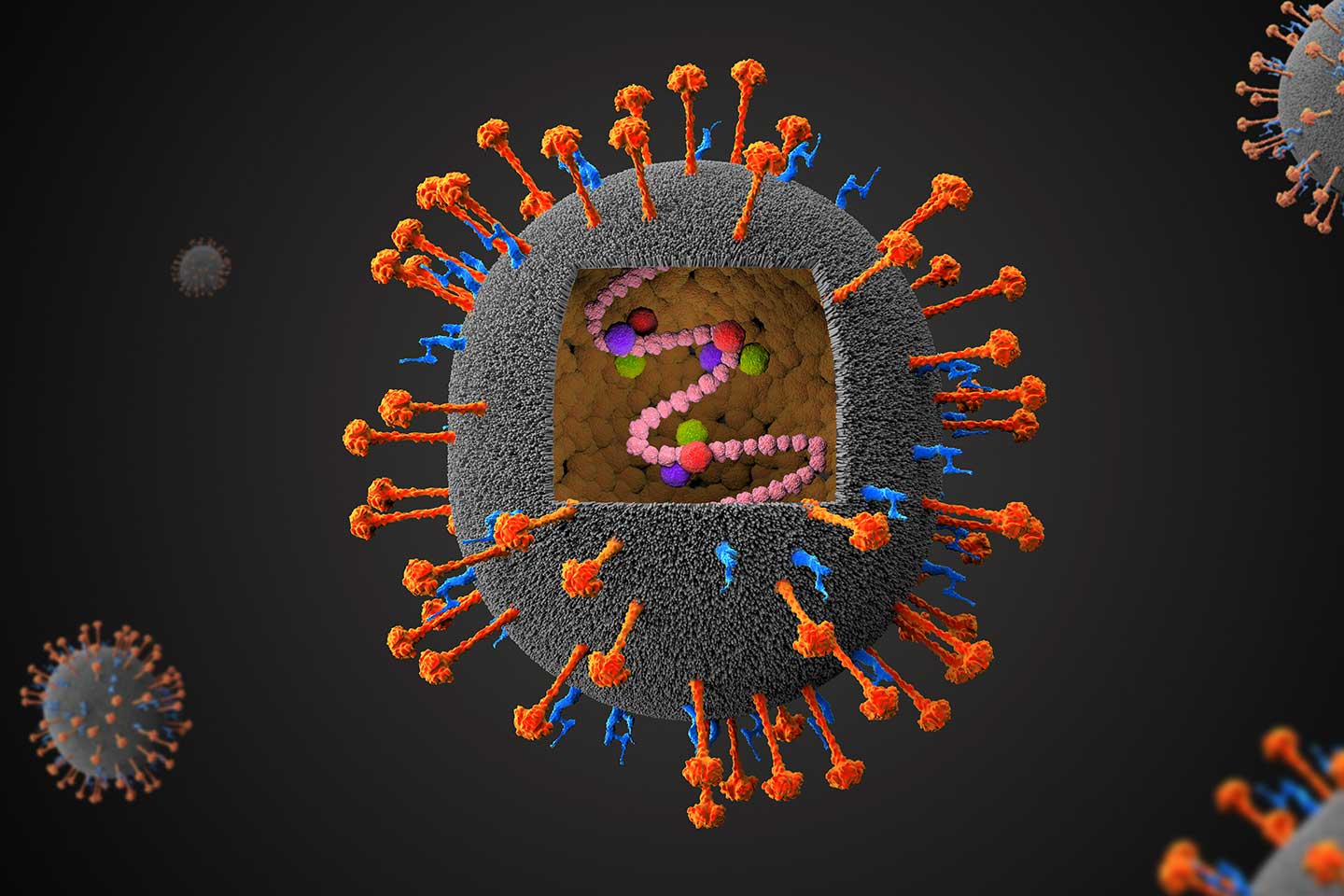

The fruit bat-borne virus Nipah literally kills 90% of those infected with it. There is no treatment or cure. This highly contagious virus can lurk in your body for 45 days before symptoms are recognized. This means contact tracing is many times harder to implement.

The Nipah virus was first discovered in 1999 in Malaysia, and it produces nightmarish symptoms like severe brain swelling, seizures, and vomiting.

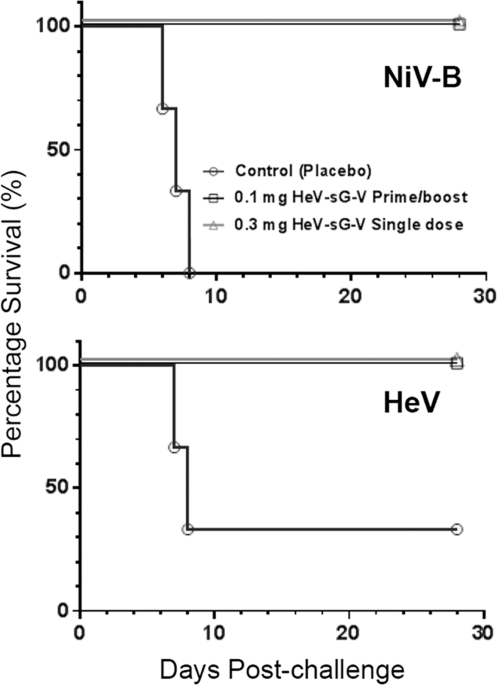

Outbreaks of the Nipah virus in the south and south-east Asia demonstrate its extremely deadly and kills between 40% to 75% of those infected. Keep in mind Covid-19’s fatality rate is around 1%.

The World Health Organization (WHO) lists it as one of 16 priority pathogens for research and development due to its potential to trigger a pandemic. Nipah is just one of 260 known viruses with pandemic potential.

Nipah also has an exceptionally high rate of mutation, and there are growing fears a strain could mutate any day that makes it much more infectious. It could spread rapidly across the globe in the same way Covid-19 spread. Unlike Covid-19, the Nipah virus could spread from China and from a maze of interconnected countries in South East Asia, easily making it accessible to the rest of the world.

Covid-19 has killed over 2.5 million people worldwide. If the Nipah virus becomes a pandemic, Dr. Melanie Saville, director of the Vaccine Research and Development Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), says it could be the next “big one.” Literally, billions of people could die from it.

Nipah is another grave threat of a zoonotic disease which means it’s a virus that can jump from animals to humans. This is becoming a big concern as human populations expand and wildlife habitats get pushed back. Zoonotic diseases, viruses like Nipah are becoming a growing threat. The Nipah virus was first discovered when an infected pig was found by farmers in Malaysia.

Dr. Rebecca Dutch, the Chairperson of the University of Kentucky’s Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry and a world leader in the study of viruses, told the British Sun Newspaper that no current Nipah outbreaks in the world when they interviewed her. She was at the time clearly unaware of the outbreak taking place in China. However, she did assert the virus does occur periodically, and it is “extremely likely” we will see cases in the future. Further, she insisted…

“Nipah is one of the viruses that could absolutely be the cause of a new pandemic.”

She pointed out that like…

“Many other viruses in that family (like measles) transmit well between people, so there is concern that a Nipah variant with increased transmission could arise.”

“Nipah has been shown to transmit through food, as well as via contact with human or animal excretions.”

Yet, a variant could develop that makes it a very infectious airborne virus like Covid-19. Based on the cover-up taking place in China, Nipah may be every bit as contagious as Covid-19 already.

Experts warn that besides fruit bats, pigs have caught the disease by eating infected mangoes and have been proven capable of passing the virus to humans. As of late February, it’s believed that one million pigs believed to be infected with the Nipah virus were slaughtered in Malaysia to prevent them from transferring it to humans.

Dr. Jonathan Epstein, vice president for science and outreach at the EcoHealth Alliance, how alarmed he and other scientists are about the Nipah virus and its potential as a pandemic far worse than Covid-19…

“We know very little about the genetic variety of Nipah-related viruses in bats, and what we don’t want to happen is for a strain to emerge that is more transmissible among people.”

“So far, Nipah is spread among close contact with an infected person, particularly someone with respiratory illness through droplets, and we generally haven’t seen large chains of transmission.”

“However, given enough opportunity to spread from bats to people, and among people, a strain could emerge that is better adapted to spreading among people. That’s what is believed to have happened with Covid-19.”

“This is a zoonotic virus (also known as zoonoses) caused by germs that spread between animals and people. It is knocking on the door, and we have to really work now to understand where human cases are occurring and try to reduce opportunities for a spillover so that it never gets the chance to adapt to humans.”

The cover-up underway in China of the Nipah virus could mutate into the most deadly pandemic mankind has ever been faced. Perhaps worse than the Black D (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality, or The Plague), a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Afro-Eurasia from 1346–53. It is considered the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history and has been estimated to have killed 75–200 million people in Eurasia and North Africa, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351.

Environmental writer John Vidal, who is working on a book revealing the links between nature and disease, predicted the world would soon face a new Black Death-scale pandemic. He argues that…

“Given the popularity of air travel and global trade, a virus could rampage across the world, unknowingly spread by asymptomatic carriers, in a few weeks, killing tens of millions of

“Mankind has changed its relationship with both wild and farmed animals, destroying their habitats and crowding them together - and the process... is only accelerating.”

“If we fail to appreciate the seriousness of the situation, this present pandemic may be only a precursor to something far graver still.”

The spread of the Nipah Virus throughout Malaysia and now China is not making headlines in the United States. The silence and cover-up in China this time may not cost 600,000 American lives; it could cost 100 million lives if it has mutated and can be transmitted by air particles, human shedding, and the food supply.