China, Asia, and the Changing Strategic Importance of the Gulf and MENA Region

October 14, 2021

The shift in America’s strategic focus from fighting terrorism in the Middle East – specifically in Afghanistan as well as Iraq and Syria – to competition with China has led to a focus on possible confrontation with China in military terms, including dealing with Taiwan and the South China Sea. At the same time, the increases in U.S. domestic natural gas and oil production have led many to believe the U.S. has far less need to ensure the smooth flow of energy exports from the Gulf and the MENA region.

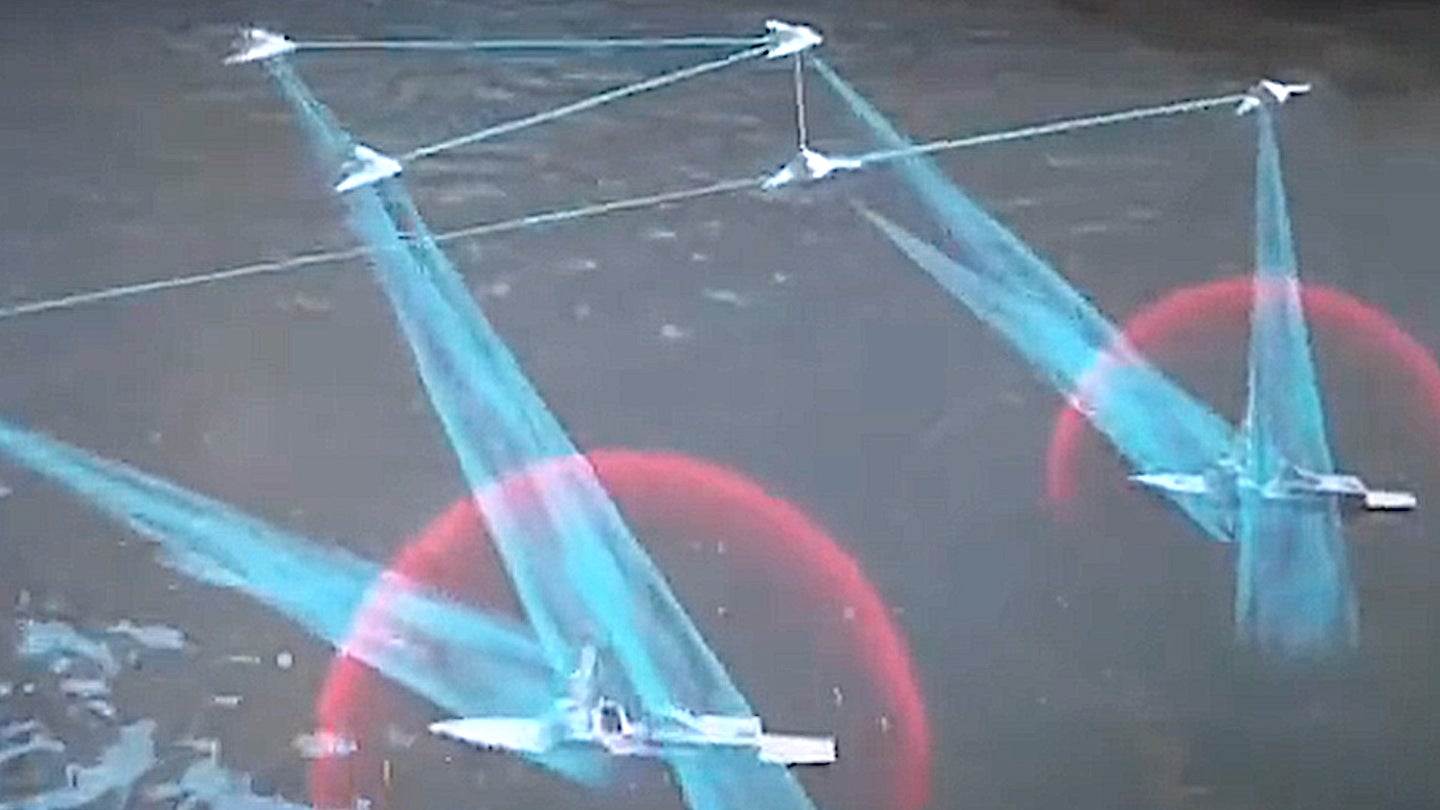

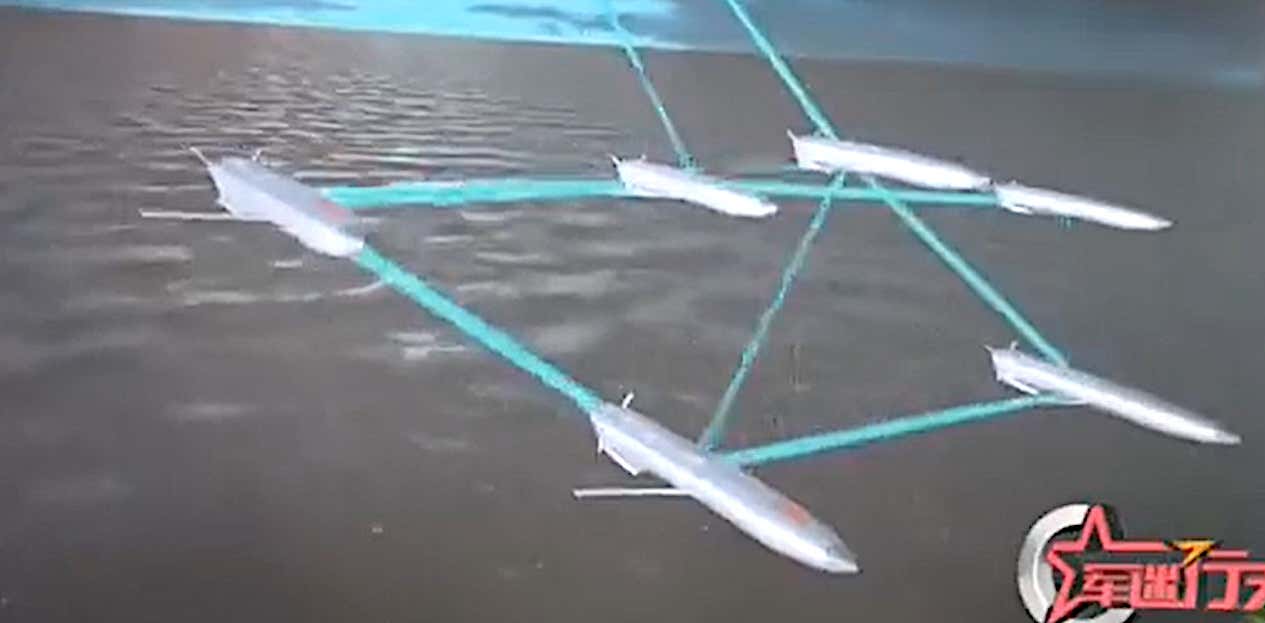

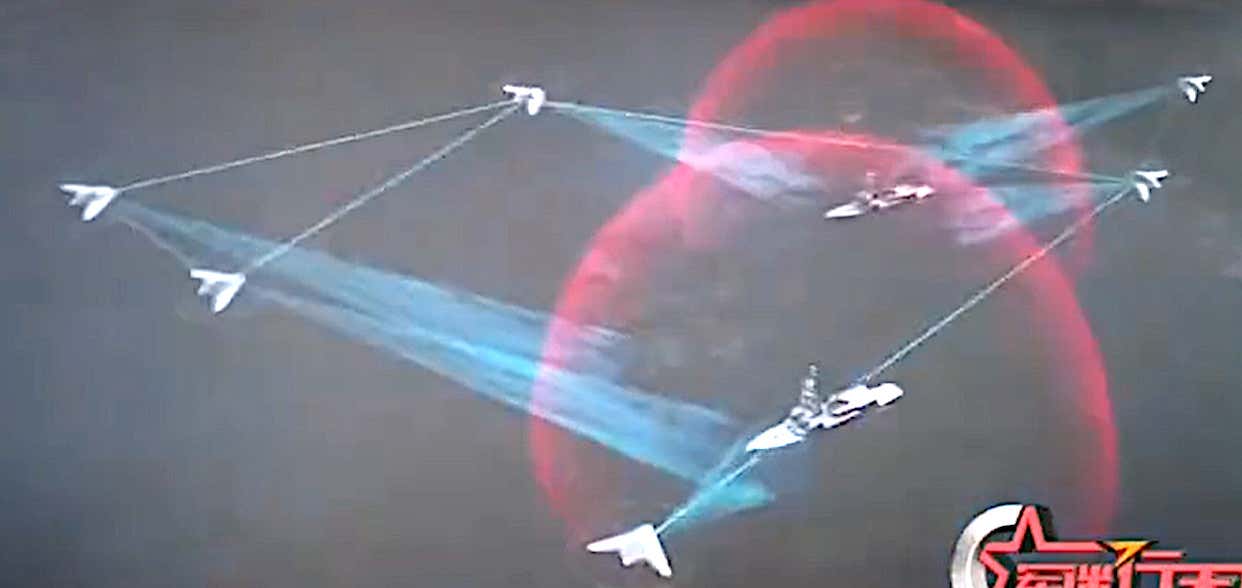

Global and White Area Competition

There are good reasons to challenge both sets of assumptions. First, China’s expansion as a great power is global, not limited to the Eastern Pacific, Taiwan, and the South China Sea. It is seeking to compete directly with the U.S. in virtually every aspect of military development and technology; to develop its own power projection capabilities; and to expand its influence and control in Central Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, the Gulf, the MENA region, Europe, Africa, and Latin America. It does not separate its military or civil efforts, and its “belt and road” economic programs are strategic in character – as well as a form of “white area” competition – and are as serious a challenge to the U.S. as are China’s growing capabilities for gray area warfare and higher levels of conflict.

More generally, the U.S. cannot let itself be trapped into focusing on the areas of direct military competition where China has the greatest advantages in terms of strategic geography and warfighting capability. The U.S. may or may not be able to challenge China indefinitely in an effort to secure the independence of Taiwan or freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, but even today, U.S. studies and wargames find the past U.S. advantage has sharply eroded and that the U.S. can “lose” some possible war scenarios.

If the U.S. is to successfully deter China and coerce it into peaceful competition and cooperation, then the U.S. must compete on a global level – confronting China with the threat of a local confrontation would be more costly in global terms than the victory is worth. It must match – or outmatch – China’s advantages in terms of countervailing powers in the Eastern Pacific with U.S. strategic leverage in other areas and do so in Chinese terms.

This means exploiting advantages in political and economic competition as well as military competition. Such “white area” competition may not be warfare in the literal sense but – as both current Chinese strategic doctrine and Sun Tzu make clear – victory is best achieved by avoiding or limiting war. A reliance on military means not only is costly in ways that have only minimal civil benefits, it presents massive risks in terms of the burden military spending places on the national economy, the cost of any major theater conflict to the U.S. and its strategic partners, and the risk – however limited – of an escalation to nuclear war.

The Growing Importance of Gulf and MENA Exports to China and Asia

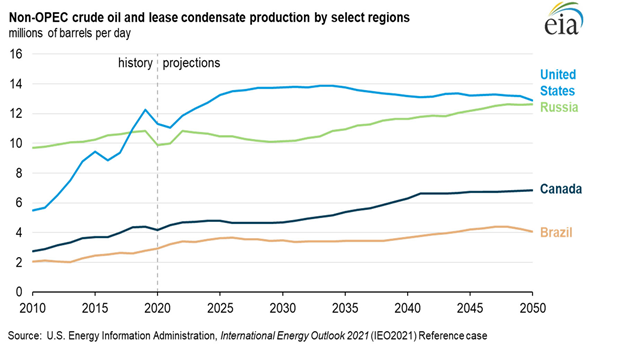

Second, direct U.S. dependence on oil imports from the MENA region may have gone down to the point where the U.S. is nearly self-sufficient, but the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) makes it clear that the period of U.S. “independence” is uncertain, and much depends on the success of programs that will substitute renewables for fossil fuels – programs that the current energy crisis makes clear are uncertain in terms of volume of output and price.

More importantly, the latest EIA projections issued in October 2021 make it clear that China and Asia will have a sharply growing dependence on MENA and Gulf petroleum exports that may well extend through 2050. Moreover, the same projections show the limits to Russian and other sources of exports. The degree of U.S. influence and strategic partnerships in the MENA region give the U.S. a major potential strategic advantage – one that may well be more important in practice than the past effort to secure key sources of oil exports to the United States.

The data – as the EIA makes clear in depth – are uncertain, and many different energy futures are possible even with today’s knowledge of energy resources and technology. The EIA projections do, however, precede the current crisis in Chinese coal supplies and the role of renewables in Europe, and even a quick parametric review of the EIA data will make it clear that it is highly unlikely that the EIA projections through 2040 will not be broadly correct unless a truly massive breakthrough takes place in some form of renewable or nuclear energy supply.

Putting Gulf and MENA Energy Production into Perspective

The MENA region has a wide range of energy exporters, including Algeria, Libya, Egypt, and Syria, as well as the states of the Arab/Persian Gulf – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen. The volume of exports varies according to market condition, local conflicts, developments in supply, and, now, the impact of Covid-19 – as do the price of crude oil, petroleum products, and gas exports.

Exports to Asia are largely driven by exports from the Arab/Persian Gulf, and – to the extent there exist hard data on something approaching a “normal” or pre-Covid year – the EIA estimates that they totaled some 20.7 million barrels per day (MMBD) through the Strait of Hormuz in 2018, plus 2.7 MMBD that passed through pipelines from Saudi Arabia and the UAE that went to ports in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. This was a total of 23.4 MMBD or some 37% of all global maritime exports and 23% of all global consumption of crude oil, condensate, and petroleum products.1 The key consumers were China, India, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and “other Asia,” plus a limited continued flow to the United States.

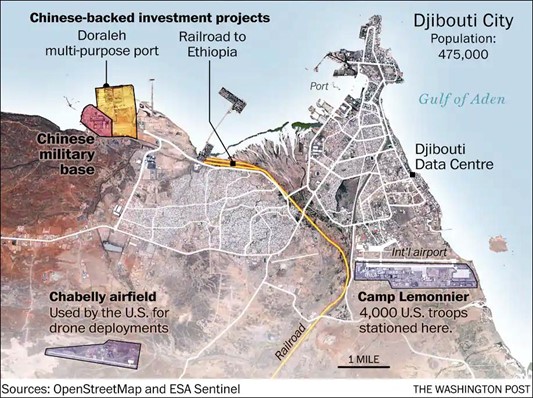

China’s Maritime Silk Road and Current Dependence on Oil Imports

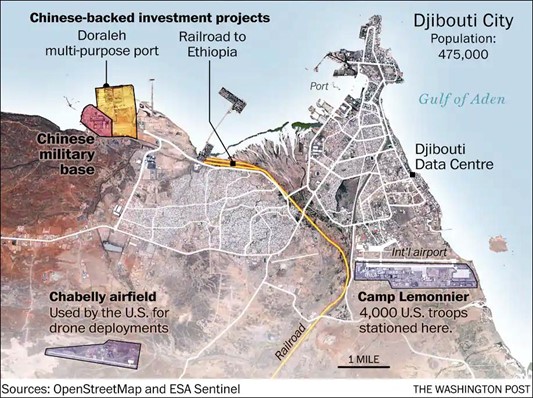

As

Figure One shows, this flow was part of a maritime “silk road” of critical strategic importance to China, not only for the flow of energy to China but for the flow of Chinese exports to Asia, the Middle East, and Europe through the Suez Canal. China clearly recognizes the importance of this route, not only for global trade but for trade within Asia and the Indian Ocean region, as the Table in

Figure One illustrates port and basing activity in Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea area, and East Africa.

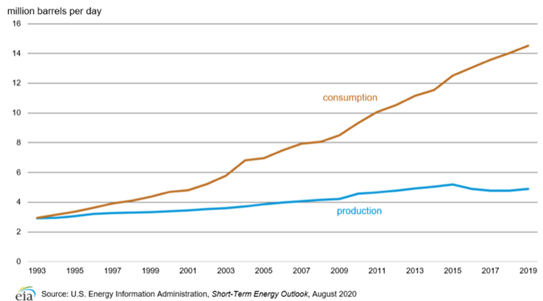

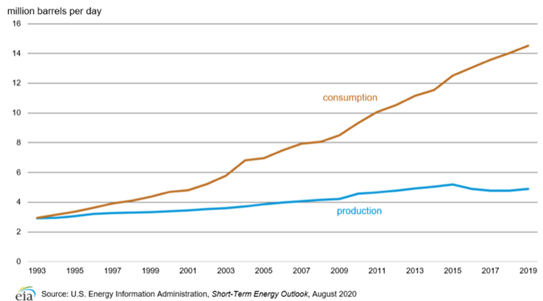

Figure Two puts China’s recent dependence in a more detailed perspective, showing the degree to which it has sought to diversify its sources of petroleum imports. At the same time, this table is based on Department of Defense (DoD) estimates that not only date back to a pre-Covid period, they date back to a time when China had not yet experienced its current crisis in coal supply, the U.S. commitment to limiting nuclear energy, and the U.S. agreement to place so much future strategic dependence on renewables and alternative energy supplies.

Both figures illustrate a level of Chinese dependence that now makes the Gulf region and the maritime routes a vital strategic interest to the United State. Important as freedom of navigation may be in the South China Sea and to preserving the independence of Taiwan, the military capability to dominate the maritime routes west of the Strait of Malacca and in the Indian Ocean is critical to China, and it offers the United States a significant advantage in countervailing power relative to China.

Chinese and Asian Economic Growth Mean Massive Increases in Energy Demand and in Flow of Imports from MENA

It is not China or Asia’s current dependence on energy imports, however, that determines the strategic importance of MENA and Gulf exports. The U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) has just released an updated version of its

International Energy Outlook or IEO.2This report is perhaps the most sophisticated estimate of future energy use available, although the International Energy Administration also has excellent modeling capability as do a number of global oil companies, research institutions, and commercial research centers.

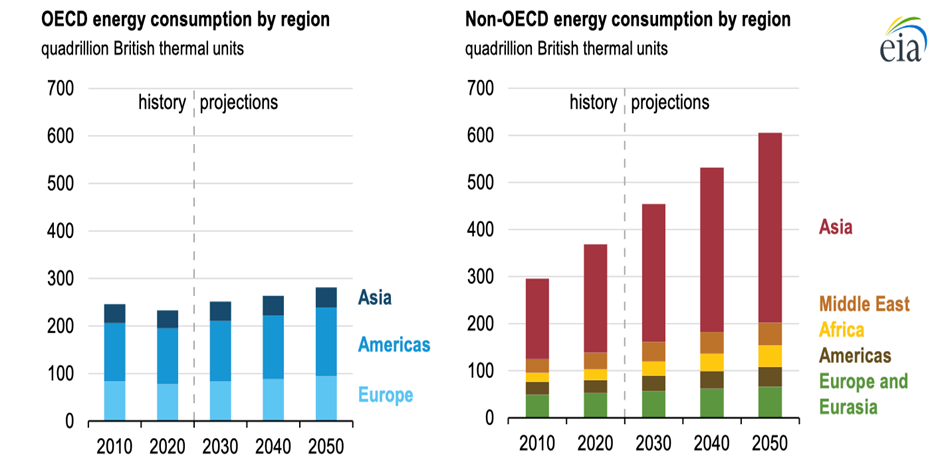

Figure Three shows that this IEO report projects a massive increase in Asian economic growth in non-Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) states, including China. This rise is far smaller for the developed Asian states in the OECD like America’s key strategic partners, but it is striking in the case of India and a wide range of other states – many of which rely on MENA exports.

Figure Four provides a more detailed breakout of the rise in Chinese and other Asian liquid fuel consumption. It projects a sustained rise in Chinese demand through at least 2035 and a far sharper rise in demand from India and other non-OECD states that means if China and/or Russia should displace the U.S. in strategic influence in the Gulf and MENA area, it would result in a major increase in their strategic leverage over much of Asia.3

Both figures project a steady increase in the strategic importance of the Gulf and MENA area directly relating to China and in creating a stable base for U.S. global competition with China in the many parts of the world where China is seeking to expand its “white area” leverage and could attempt to use “gray area” military options.

The narrative section of the IEO report notes that:4

The regions with the fastest-growing economies in the IEO2021 Reference case are non-OECD countries in Asia. India’s growth is greatest, but the WEPS regions7 of Other non-OECD Asia, Africa, China, and Other non-OECD Europe and Eurasia remain leaders in economic growth as well. Although China continues to grow at an average rate equal to Africa and Other non-OECD Europe and Eurasia, its growth notably slows throughout the projection period. Together, these top five growth regions were home to 70% of the world’s population in 2020 and 44% of GDP. By 2050, these shares grow to 73% and 59%, respectively.

Economic growth varies widely among Asian regions in the IEO2021 Reference case. Most notably, the projected GDP growth rate in China slows considerably compared with its growth rate from 2000 to 2010, when GDP increased by an average of over 10% per year. We also project slower economic growth for Japan and South Korea, illustrating the interconnectedness of Asian economies, as the decline in Chinese demand and trade for intermediate and finished goods, in addition to other structural and demographic factors, affects economic growth in these neighboring countries.

It should also be noted that increases in Russian influence in the MENA and Gulf areas relative to the U.S. – particularly a major rise in Russian influence over oil production and prices as a result of its negotiations with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Gulf oil producers – could increase Russian and potentially Russian-Chinese strategic influence, both in Asia and on a broader global level.

Rising Global and Asian Dependence on Liquid Fuels Through 2050

These increases in the consumption of liquid fossil fuels occur, in spite of the fact that

Figure Five shows IEO’s – what very well might be – optimistic assumptions about the future global ability to increase supplies of renewables and natural gas as well as the need to substitute petroleum for coal. It also, however, flags the increasing importance of Russia as a natural gas supplier.

Here, the IEO data raise another issue that needs separate modeling in detail, and this is the combined strategic impact of China as an importer and Russia as a supplier. If energy is treated as a weapon of “white area” influence, Russia and China need to be considered in terms of strategic competition with the United States and U.S. strategic partners – and Russia’s potential strength as a supplier could, in some scenarios, partially balance China’s vulnerability.

As for the broader overview of dependence on liquid fuels in the IEO, the report states that:5

Oil and natural gas production will continue to grow, mainly to support increasing energy consumption in developing Asian economies…Driven by increasing populations and fast-growing economies, consumption of liquid fuels will grow the most in non-OECD Asia, where total consumption nearly doubles by 2050 from 2020 levels in the Reference case.

Because these countries will consume more liquid fuels than they produce in the Reference case, we project that non-OECD Asia will supplement local production with increased imports of crude oil and finished petroleum products. The increased imports will primarily be supported by increased production in the Middle East. In the Reference case, by 2050, non-OECD Asia will become the largest importer of natural gas, and Russia will become the largest net exporter of natural gas.

Gulf versus Other Sources of Petroleum Production

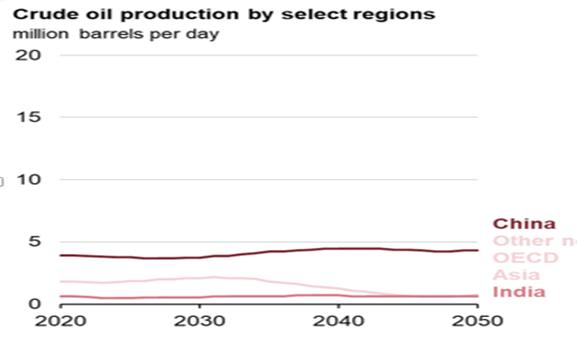

Figure Six supplements the previous data by showing the projected trends in petroleum projection from key sources through 2050. The key role of the MENA region – which is clearly dominated by the Arab/Persian Gulf – is clear. So are the sharp limits to the increases in Russian, U.S., Canadian, and Brazilian production.

The good news is that the U.S. is projected to sustain a high level of independence from petroleum imports if it meets its goals for expanding renewables. The mixed news, however, is just how critical U.S. ties to its strategic partners in the Gulf and MENA areas will remain.

U.S. Competition with China and Russia, the Gulf and MENA Region, and Countervailing Power

Given these trends, the strategic importance of the MENA region and the Gulf is at least as important as it was during the peak period of U.S. dependence on petroleum imports – and may well be higher now. So are America’s ability to deter conflicts and threats to and within the region as well as its ability to protect and work with its strategic partners.

U.S. strategic partnerships in the MENA region have become a critical tool in maintaining U.S. countervailing power against China, in aiding America’s partners in Asia as well as in addressing the continuing threat of instability – and terrorism and extremism – in the MENA region. The strategic priority of the MENA region remains as high as ever. It has shifted, however, from American energy dependence to competing with China and Russia and to maintaining a global economic system that favors the United States.

These trends also illustrate the critical importance of expanding the U.S. approach to competing with China beyond the military dimension to address the “civil” political and economic power as well as influence at a global level. Energy is only one aspect of “white area” competition in technology and STEM research, manufacturing capability, trade, and infrastructure. Taken together, they are at least as important as military power, and they offer far more opportunities to transition from competition and confrontation to some form of viable cooperation. Even in the short term, “military victory” through any serious form of actual warfighting is threatening to become an oxymoron. Effective civil-military efforts have a very different potential outcome.

Figure One: The Maritime Silk Road in the Indian Ocean and Beyond - I

Source: Richard Ghiasy, Fei Su and Lora Saalman, The Maritime Silk Road, Security Implications, SIPRI, 2018, pp. 6, 29, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/the-21st-century-maritime-silk-road.pdf. Map by Christian Dietrich.

Figure One: The Maritime Silk Road in the Indian Ocean and Beyond - II

Source: Richard Ghiasy, Fei Su and Lora Saalman, The Maritime Silk Road, Security Implications, SIPRI, 2018, pp. 6, 29, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/the-21st-century-maritime-silk-road.pdf. Map by Christian Dietrich.

Figure One: The Maritime Silk Road in the Indian Ocean and Beyond - II

Source: Open street Map; ESA Sentinel; Washington Post; and Juan Cole, “The Dragon Arrives: 1st Chinese overseas Military Base in Djibouti,” Informed Comment, August 2, 2017.

Figure Two: China’s Strategic Dependence on Gulf and Other Crude Imports in 2019

Source: Open street Map; ESA Sentinel; Washington Post; and Juan Cole, “The Dragon Arrives: 1st Chinese overseas Military Base in Djibouti,” Informed Comment, August 2, 2017.

Figure Two: China’s Strategic Dependence on Gulf and Other Crude Imports in 2019

China’s Rising Dependence on Petroleum Imports 1993-2019

Key Chinese Suppliers in 2019

Key Chinese Suppliers in 2019

Source: Adapted from U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2020, Reference Case, August 21, 2020, p. 170; and EIA, “China,” September 30, 2020, International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Source: Adapted from U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2020, Reference Case, August 21, 2020, p. 170; and EIA, “China,” September 30, 2020, International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

washingtonnewsday.com

washingtonnewsday.com