Leaving Afghanistan Will Make America Less Safe - War on the Rocks

Bruce Hoffman and Jacob Ware

12-15 minutes

America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan should be cause for rejoicing. But conditions in the country today, and the historical record of past U.S. withdrawals from similar conflicts, suggest that it will only create more problems. By leaving, Washington is vindicating an aphorism attributed to a captured Taliban fighter over a decade ago:

“You have the watches. We have the time.”

Proving the Taliban wrong is not a politically unaffordable extravagance. It merely requires retaining a couple of thousand elite special operations, intelligence, and support personnel in Afghanistan. Otherwise, the risk is that this will be the fourth time in as many decades that a U.S. military withdrawal encourages terrorists by showing the weakness of U.S. resolve. When America left Beirut in 1983, Mogadishu a decade later, and Iraq in 2011, the result was more terrorism, not less.

Indeed, no one

understood the significance of America’s past retreats better than Osama bin Laden. In a 1997 interview,

he recalled how the deaths of 241 U.S. marines in the Beirut barracks bombing had compelled President Ronald Reagan to order a withdrawal from Lebanon within five months. This led to the collapse of the multinational force in Lebanon — of which the Marines were the lynchpin — and plunged Lebanon into further chaos. The main beneficiary was Hizballah, the shadowy terrorist group responsible for the attack. In the decades since, Hizballah’s success influenced other terrorist leaders and groups, including bin Laden and al-Qaeda.

By 1993, the U.S. military was deeply involved in a United Nations mission to restore stability in Somalia and feed starving citizens enmeshed in civil war. But that October, a plan to arrest a local warlord’s paymaster and chief lieutenant went disastrously awry. Fifteen U.S. Army Rangers and three Delta Force commandos were killed in an uncontrolled spiral of urban combat depicted in the

book and

film Black Hawk Down. In some of the most gripping footage ever broadcast live on television, an injured U.S. Army helicopter pilot was seen being paraded through the streets of Mogadishu by a chanting, gun-wielding mob. President Bill Clinton reacted quickly to the incident. Scrambling to preempt criticism from Congress, the media, and the American public,

he set March 31, 1994, as the firm date for the withdrawal of all American forces there — regardless of whether the multinational, U.N.-led humanitarian aid mission had been successfully completed or not.

Members of the al-Qaeda movement had both trained and fought alongside the Somali militiamen that fateful day in Mogadishu. To bin Laden’s thinking, it had taken the deaths of 241 U.S. marines to get the U.S. out of Lebanon in 1983. A decade later, the loss of less than a tenth of that number had prompted an identical reaction. As bin Laden explained in his

1996 declaration of war on the United States:

[W]hen dozens of your troops were killed in minor battles, and one American pilot was dragged in the streets of Mogadishu, you left the area defeated, carrying your dead in disappointment and humiliation. Clinton appeared in front of the whole world threatening and promising revenge. But these threats were merely a preparation for withdrawal. God has dishonored you when you withdrew, and it clearly showed your weaknesses and powerlessness.

Bin Laden was emboldened to believe that if U.S. foreign policy could be influenced by a score of military deaths in an East African backwater, it could be changed fundamentally by thousands of civilian deaths in the United States itself. Thus, the road to 9/11 started in Beirut, led a decade later to Mogadishu, then wound its way through Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, and Aden before arriving in New York City, Washington, D.C., and a field outside of Shanksville, Pennsylvania. No one could have anticipated the exact chain of events. But the retreats from both Beirut and Mogadishu nonetheless set those events in motion by feeding a dangerous perception of American weakness.

Some analysts have argued that the situation is different now precisely because of the 9/11 attacks. Washington did not take

terrorism sufficiently seriously in the 1990s, but

since then, the country has built up a huge counter-terrorism bureaucracy that makes staying in Afghanistan unnecessary. Now Washington can protect the homeland by using enhanced intelligence, special operations forces, and precision-guided, stand-off munitions. With these resources, over-the-horizon military and intelligence assets will be able to quickly identify and address any new threats.

This also was the logic behind the

withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq in 2011. But the disastrous consequences were soon felt with the rise of the Islamic State. Washington was overconfident in its counter-terrorism capabilities and underestimated the new terrorist variant it faced. As with Hizballah in the 1980s and al-Qaeda in the 1990s, the results proved tragic. Once again the

desire to disengage when confronted by stubborn, resilient non-state adversaries created conditions ripe for terrorist exploitation. The vacuum in Iraq was rapidly filled by new extremist groups. President Barack Obama’s curt dismissal of the embryonic Islamic State as “

a jayvee team” would come to haunt him less than six months later, after the terrorist blitzkrieg that conquered western Iraq and stormed across the border into Syria. The Islamic State soon inspired a series of domestic attacks in multiple Western countries. Within months, it had dragged an international coalition that would eventually involve 83 countries back into maw of Middle Eastern conflict.

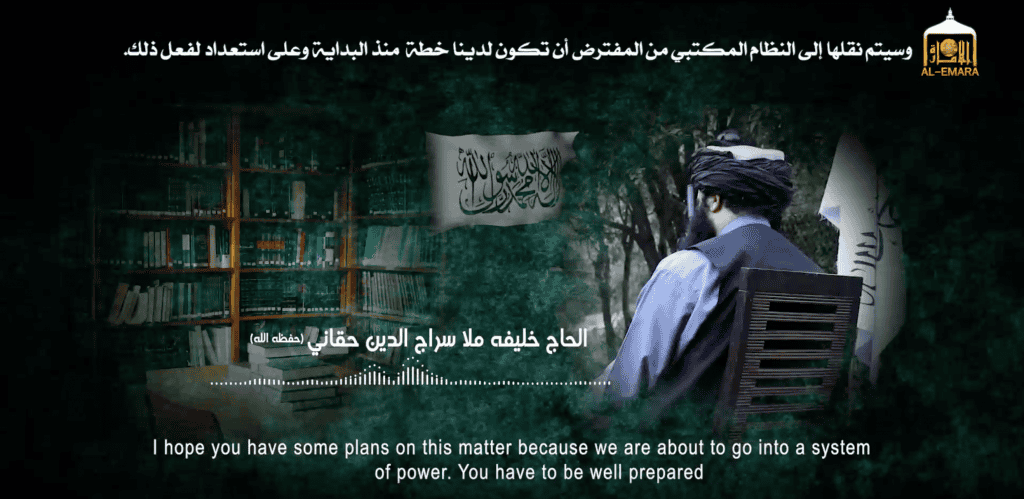

Today in Afghanistan, the United States is similarly understating and underestimating the threat posed by the Taliban. If anything, the situation in Afghanistan is more dangerous. When America withdrew from Iraq, there was no single terrorist adversary capable of toppling democratically elected Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki in Baghdad. The Taliban, however, has that potential and makes no secret of its intention to re-impose theocratic rule over Afghanistan. It therefore poses an existential threat to the democratically elected government of President Ashraf Ghani in a way that no contender had in Iraq a decade ago. Moreover, the Taliban’s longstanding, close alliances with al-Qaeda, the Haqqani network, and Pakistan’s Tehrik-i-Taliban endow it with additional attack capabilities that did not exist in Iraq at the time of 2011 U.S. withdrawal.

Against this backdrop, there are two specific risks associated with America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. First, the international terrorist threat that necessitated invading that country following the 9/11 attacks remains. Al-Qaeda is

undefeated. Its intimate, longstanding relationship with the Taliban suggests that al-Qaeda will be the beneficiary of the territorial and political gains its Afghan partners are

poised to achieve in a post-U.S. Afghanistan. In 2019, in fact, as negotiations with the United States were underway, Taliban leaders

reportedly sought to personally reassure Hamza bin Laden, Osama bin Laden’s son and the al-Qaeda heir apparent, “that the Islamic Emirate would not break its historical ties with al-Qaeda for any price.” Indeed, two al-Qaeda operatives recently

praised the Taliban for its support. “Thanks to Afghans for the protection of comrades-in-arms,” a spokesman for the group gushed. Even if the Taliban makes good on its promise to restrain al-Qaeda from attacking the United States and the West from an Afghan base, this does not preclude al-Qaeda from using Afghanistan to destabilize this already highly volatile region. In 2008, a series of coordinated suicide attacks in Mumbai by Lashkar-e-Taiba — another close al-Qaeda ally —

brought India and Pakistan to the brink of nuclear war. It is worth recalling, too, that both of al-Qaeda’s most recent new franchises are focused on South Asia generally and on Kashmir specifically.

America’s counter-terror resources are also likely to be stretched particularly thin going forward, making managing the threat from afar even less plausible. Afghanistan is now only one of many terrorist hotspots around the globe, which seem to be multiplying. Security conditions are deteriorating in

Mozambique and the Sahel, for instance, while sectarian clashes in

Northern Ireland raise fears of “The Troubles” returning. At home,

far-right terrorism runs rampant. Even if U.S. intelligence agencies find ways to effectively

manage terrorist safe havens without soldiers on the ground, their attention and vigilance will necessarily be spread thin.

The second risk is that withdrawal from Afghanistan will weaken, rather than strengthen, Washington against peer competitors. The United States, rightly or wrongly, is

shifting from prioritizing counter-terrorism toward a great-power competition posture. But thinking of the two as zero sum is a

mistake. China has prioritized

embedding itself in local contexts for years; Russia and Iran have been practicing their irregular warfare strategies in Ukraine, in Yemen, and, most aggressively, in Syria. Indeed, at least one Iran-backed Shiite militia in Iraq has already drawn inspiration from the Taliban’s success. Qais al Khazali, leader of Asaib Ahl al-Haq (League of the Righteous),

observed just the other day that “the Afghan way is the only way to make [the United States] leave [Iraq].” Every military setback — whether in Lebanon, Somalia, Iraq, or Afghanistan — illuminates a path by which great-power adversaries see they can defeat the United States.

It is no coincidence that Russia has

provided support to the Taliban, likely aiming to help sap America’s energy and spirit and encourage America’s withdrawal from the region.

Yet rather than heed present risks or past warnings, President Joe Biden, like President Trump before him, seems more concerned with the political capital to be milked from ending America’s longest war. As in Beirut and Mogadishu, Washington appears largely satisfied that our military personnel will no longer be in harm’s way. But a responsible strategy need not involve gratuitously exposing troops to harm. In fact, the last American

combat fatality in Afghanistan was more than a year ago. The current troop level there, approximately 3,500 personnel, accounts for 0.27 percent of America’s active duty forces — hardly a drain on the resources of even a declining superpower. Maintaining this small contingent would have a significant force-multiplying effect. It would provide an immediate trip wire to deal with any serious terrorist threat while also bolstering the Afghan government and improving its security forces.

Moreover, maintaining a limited, elite presence in a country sharing a border with China might

well be in America’s strategic interests as the “new cold war” heats up. Simply abandoning Afghanistan will not help the counter-terrorism fight and it is unlikely to help with great-power competition either.

There are no perfect

options. But instead of turning its back on Afghanistan, the United States should

shift its rhetoric in the “Global War on Terror” away from “winning” and “losing” and toward “managing” and “accepting.” This would facilitate an ongoing but limited troop presence with a clear homeland security,

not nation-building, brief.

Keeping a small number of elite troops in Afghanistan, while unlikely to elicit roars of approval at campaign rallies in the 2024 presidential race, would likely keep both the Taliban and al-Qaeda at bay in the country while protecting a forward operating base on

China’s and

Russia’s doorstep. Withdrawal, by contrast, will be universally seen as defeat. As with bin Laden 25 years ago, it will give a rhetorical

victory to terrorists the world over. And it will boost the morale of state adversaries that benefit from the perception of U.S. weakness.

Bruce Hoffman is the senior fellow for counterterrorism & homeland security at the Council on Foreign Relations and a professor at Georgetown University. Jacob Ware is a research associate for counterterrorism at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Image:

U.S. Air Force (Photo by Staff Sgt. Kylee Gardner

Posted For fair use

America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan should be cause for rejoicing. But conditions in the country today, and the historical record of past U.S.

warontherocks.com

Via Reuters

Via Reuters

Camp Antonik handover ceremony, via Afghan Ministry of Defense

Camp Antonik handover ceremony, via Afghan Ministry of Defense

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/Q4YZSXL25JAHNOYI56DCRKEDSA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/Q4YZSXL25JAHNOYI56DCRKEDSA.jpg)

This due to things being that much worse, that much more quickly than they planned for...or ... :: shrug ::

This due to things being that much worse, that much more quickly than they planned for...or ... :: shrug ::