(484) 07-31-2021-to-08-06-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(485) 08-07-2021-to-08-13-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(486) 08-14-2021-to-08-20-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

____________________________________________

Posted for fair use.....

FROM FOREVER WARS TO GREAT-POWER WARS: LESSONS LEARNED FROM OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE

STACIE L. PETTYJOHN AND BECCA WASSER

AUGUST 20, 2021

COMMENTARY

Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a two-part series on airpower and Operation Inherent Resolve. The first article explores the evolution of airpower since Operation Desert Storm.

What lessons can be gleaned from recent U.S. military operations in Iraq and Syria that are relevant for a potential future war against a great-power adversary like China or Russia?

The U.S. Department of Defense is attempting to make the long overdue pivot from focusing on the Middle East to shoring up deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and Europe by improving its ability to prevail in large-scale combat against a great power. But it is important that the Pentagon does not relegate the lessons learned from its recent operational experience in the Middle East to the trash bin. Aaron Stein and Ryan Fishel argue that the U.S. Air Force needs to prepare for proxy war scenarios akin to Syria. The Defense Department undoubtedly should learn from its experience competing with Russia and Iran in Syria below the threshold of conventional war. But it can and should also learn lessons from U.S. operations in the Middle East for great-power conflict as well.

The war to defeat the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), known as Operation Inherent Resolve, presented one of the most permissive operating environments U.S. airpower could expect. Issues that emerged in this environment are likely to be far more acute against a more capable adversary. American military operations in the Middle East highlighted clear deficiencies in some missions that would be essential to winning a future great-power conventional war. U.S. forces should address the vulnerabilities identified during this conflict related to deliberate targeting, operating in contested airspace, and integrating air- and ground-based fires to prepare for future great-power conflict.

Preplanned Airstrikes Struggle to Keep Up With the Speed of Modern Warfare

As the U.S. military prepares for war against a great power, military leaders have re-emphasized developing offensive platforms and weapons systems to improve firepower. Currently, U.S. air operations are centered around an air operations center that preplans deliberate airstrikes as a part of a 72-hour air-tasking cycle. In Operation Inherent Resolve, however, the deliberate targeting process routinely took “from days to weeks.” This proved to be too slow to keep up with a highly adaptive adversary and rapidly changing battlefield.

The deliberate targeting process struggled due to the absence of an initial list of ISIL targets, insufficient numbers of intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft to simultaneously support ground operations and deliberate target development, and a stovepiped and undermanned intelligence process. Because ISIL had few fixed targets, such as buildings or airfields, U.S. forces tried to preplan strikes against headquarters; cash and weapons stores; and oil production, processing, and distribution operations. ISIL was able to stay ahead of U.S. forces’ deliberate targeting cycle by relocating mobile targets like oil trucks or regularly transferring weapons, cash, and fighters from one location to another before deliberate targets could be approved. ISIL also hid forces and assets among civilians to further complicate targeting.

In a great-power war, U.S. forces are unlikely to have the luxury of days or weeks to plan air and missile strikes if they want to stop a fait accompli and defeat invading Chinese or Russian forces. Unlike in Operation Inherent Resolve, U.S. forces will likely have an existing prioritized target list they can take off the shelf. But, after those initial strikes, it is not clear that a 72-hour deliberate targeting process will be fast enough to keep up with the adversary or be capable of supporting all-domain operations in the way that U.S. forces are envisioning. In a fast-paced, high-intensity conflict, unexpected adversary actions, battlefield developments, and damage inflicted on U.S. forces will likely render advance planning irrelevant or inexecutable. The air-tasking cycle was created to produce effective and efficient air operations, while minimizing the risk to U.S. forces. It has worked well against less-capable adversaries. But, in a war against a great power, U.S. forces will likely need to accept more risk and inefficiency if they want to survive, let alone have a chance of winning.

Moreover, if the American goal is to halt an attack, the most important target sets — such as ships, tanks, aircraft, air defenses, and missile launchers — are likely to be mobile and thus will need to be targeted dynamically. Yet, before U.S. forces can engage mobile enemy targets, they need to be able to find them, which historically has been a significant problem. There are reasons to believe that finding mobile targets would be more difficult in a high-end conflict than it was in the desert. Planners should assume that, like ISIL, Russia and China will use unmarked forces, camouflage concealment and deception, and mobility to disguise the identity and location of their forces. A combination of forward air controllers and forward command posts may allow the United States to find some mobile targets in Europe. But the U.S. forces will likely struggle to find targets in an adversary’s heavily defended homeland and in dense urban environments. A lack of air and information superiority may further complicate targeting in a future conflict with China, as American forces may struggle to accurately target military ships from range, wasting sophisticated cruise missiles on decoys in a cluttered maritime environment. Deliberate targeting is likely to play a peripheral role in air operations against a great power because of the large number of mobile targets, the pace of operations, and the urgency associated with accomplishing certain missions.

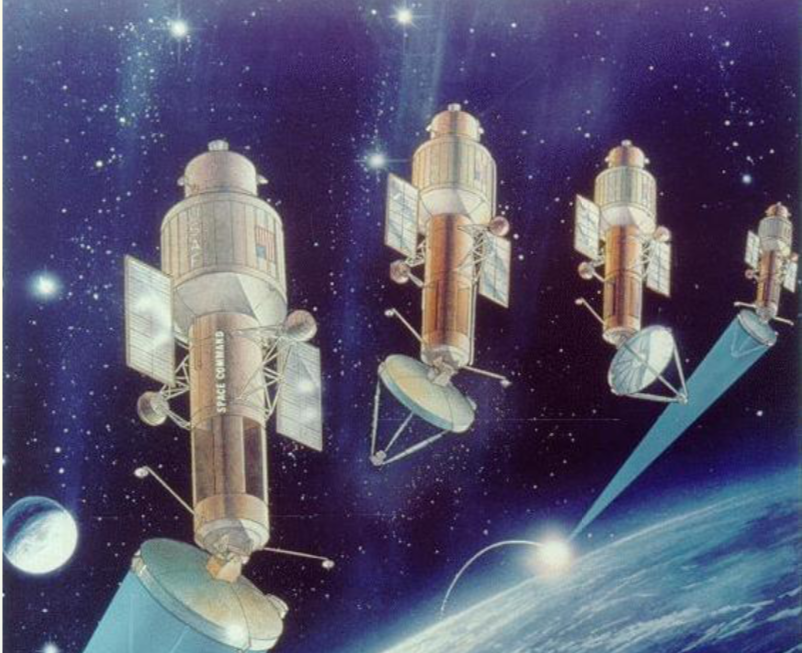

American Forces Are Not Prepared to Operate in Highly Contested Battlespaces

Preparation for future conflict with China and Russia is predicated on U.S. forces operating in a contested environment. But the recent U.S. experience in Syria in merely a congested air environment — rather than a contested one — illustrates just how difficult this will be for U.S. forces as they contend with different forms of physical and informational denial.

Unlike China or Russia, ISIL did not have the advanced capabilities to challenge American forces in the air, at sea, or in space. But U.S. forces did find themselves operating in close proximity to more-capable Russian, Syrian, and Iranian air forces in Syria during Inherent Resolve. Some U.S. troops found that they were unprepared and uncomfortable maneuvering around potentially hostile forces in a busy and congested air environment, where U.S. forces only had tacit approval to operate in Syrian airspace. This was further complicated by Russia’s deployment of sophisticated surface-to-air missiles, which posed a potential threat to U.S. and partner aircraft.

Years of operations without any air-to-air engagements, and in which almost every weapon released was approved at a high level and scrutinized after the fact, had left U.S. pilots initially reluctant to act in self-defense against emerging threats. While there were several air-to-air incidents, including U.S. shootdowns of a Syrian Su-22 Fitter attack aircraft and two Iranian-made Shahed 129 unmanned aerial systems, these only occurred after senior U.S. commanders stressed the importance of self-defense and initiative to troops. U.S. forces have become accustomed to needing approval before acting, which was appropriate and needed to protect innocent civilians in counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations. But the flipside is that this may have instilled a hesitancy that a great-power adversary could exploit.

Because Russia and China both have extensive integrated air and missile defense systems and mobile air defenses organic to their maneuver units, the United States will not have air supremacy at the outset of a conflict. This means that U.S. strike aircraft will not be able to loiter over an area hunting for targets without assuming great risk, and accompanied by aircraft to defend them. These U.S. forces should be authorized and prepared to undertake defensive and offensive operations because they will likely be challenged by adversary air defenses and air forces. In future great-power conflict, U.S. military personnel will need to become more risk-acceptant and empowered to act without receiving explicit approval from their commanders. This is especially true in a degraded communications environment, as commanders may not be reachable to provide authorization.

Continued.....

(485) 08-07-2021-to-08-13-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

(486) 08-14-2021-to-08-20-2021__****THE****WINDS****of****WAR****

____________________________________________

Posted for fair use.....

From Forever Wars to Great-Power Wars: Lessons Learned From Operation Inherent Resolve - War on the Rocks

Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a two-part series on airpower and Operation Inherent Resolve. The first article explores the evolution of

warontherocks.com

FROM FOREVER WARS TO GREAT-POWER WARS: LESSONS LEARNED FROM OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE

STACIE L. PETTYJOHN AND BECCA WASSER

AUGUST 20, 2021

COMMENTARY

Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a two-part series on airpower and Operation Inherent Resolve. The first article explores the evolution of airpower since Operation Desert Storm.

What lessons can be gleaned from recent U.S. military operations in Iraq and Syria that are relevant for a potential future war against a great-power adversary like China or Russia?

The U.S. Department of Defense is attempting to make the long overdue pivot from focusing on the Middle East to shoring up deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and Europe by improving its ability to prevail in large-scale combat against a great power. But it is important that the Pentagon does not relegate the lessons learned from its recent operational experience in the Middle East to the trash bin. Aaron Stein and Ryan Fishel argue that the U.S. Air Force needs to prepare for proxy war scenarios akin to Syria. The Defense Department undoubtedly should learn from its experience competing with Russia and Iran in Syria below the threshold of conventional war. But it can and should also learn lessons from U.S. operations in the Middle East for great-power conflict as well.

The war to defeat the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), known as Operation Inherent Resolve, presented one of the most permissive operating environments U.S. airpower could expect. Issues that emerged in this environment are likely to be far more acute against a more capable adversary. American military operations in the Middle East highlighted clear deficiencies in some missions that would be essential to winning a future great-power conventional war. U.S. forces should address the vulnerabilities identified during this conflict related to deliberate targeting, operating in contested airspace, and integrating air- and ground-based fires to prepare for future great-power conflict.

Preplanned Airstrikes Struggle to Keep Up With the Speed of Modern Warfare

As the U.S. military prepares for war against a great power, military leaders have re-emphasized developing offensive platforms and weapons systems to improve firepower. Currently, U.S. air operations are centered around an air operations center that preplans deliberate airstrikes as a part of a 72-hour air-tasking cycle. In Operation Inherent Resolve, however, the deliberate targeting process routinely took “from days to weeks.” This proved to be too slow to keep up with a highly adaptive adversary and rapidly changing battlefield.

The deliberate targeting process struggled due to the absence of an initial list of ISIL targets, insufficient numbers of intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft to simultaneously support ground operations and deliberate target development, and a stovepiped and undermanned intelligence process. Because ISIL had few fixed targets, such as buildings or airfields, U.S. forces tried to preplan strikes against headquarters; cash and weapons stores; and oil production, processing, and distribution operations. ISIL was able to stay ahead of U.S. forces’ deliberate targeting cycle by relocating mobile targets like oil trucks or regularly transferring weapons, cash, and fighters from one location to another before deliberate targets could be approved. ISIL also hid forces and assets among civilians to further complicate targeting.

In a great-power war, U.S. forces are unlikely to have the luxury of days or weeks to plan air and missile strikes if they want to stop a fait accompli and defeat invading Chinese or Russian forces. Unlike in Operation Inherent Resolve, U.S. forces will likely have an existing prioritized target list they can take off the shelf. But, after those initial strikes, it is not clear that a 72-hour deliberate targeting process will be fast enough to keep up with the adversary or be capable of supporting all-domain operations in the way that U.S. forces are envisioning. In a fast-paced, high-intensity conflict, unexpected adversary actions, battlefield developments, and damage inflicted on U.S. forces will likely render advance planning irrelevant or inexecutable. The air-tasking cycle was created to produce effective and efficient air operations, while minimizing the risk to U.S. forces. It has worked well against less-capable adversaries. But, in a war against a great power, U.S. forces will likely need to accept more risk and inefficiency if they want to survive, let alone have a chance of winning.

Moreover, if the American goal is to halt an attack, the most important target sets — such as ships, tanks, aircraft, air defenses, and missile launchers — are likely to be mobile and thus will need to be targeted dynamically. Yet, before U.S. forces can engage mobile enemy targets, they need to be able to find them, which historically has been a significant problem. There are reasons to believe that finding mobile targets would be more difficult in a high-end conflict than it was in the desert. Planners should assume that, like ISIL, Russia and China will use unmarked forces, camouflage concealment and deception, and mobility to disguise the identity and location of their forces. A combination of forward air controllers and forward command posts may allow the United States to find some mobile targets in Europe. But the U.S. forces will likely struggle to find targets in an adversary’s heavily defended homeland and in dense urban environments. A lack of air and information superiority may further complicate targeting in a future conflict with China, as American forces may struggle to accurately target military ships from range, wasting sophisticated cruise missiles on decoys in a cluttered maritime environment. Deliberate targeting is likely to play a peripheral role in air operations against a great power because of the large number of mobile targets, the pace of operations, and the urgency associated with accomplishing certain missions.

American Forces Are Not Prepared to Operate in Highly Contested Battlespaces

Preparation for future conflict with China and Russia is predicated on U.S. forces operating in a contested environment. But the recent U.S. experience in Syria in merely a congested air environment — rather than a contested one — illustrates just how difficult this will be for U.S. forces as they contend with different forms of physical and informational denial.

Unlike China or Russia, ISIL did not have the advanced capabilities to challenge American forces in the air, at sea, or in space. But U.S. forces did find themselves operating in close proximity to more-capable Russian, Syrian, and Iranian air forces in Syria during Inherent Resolve. Some U.S. troops found that they were unprepared and uncomfortable maneuvering around potentially hostile forces in a busy and congested air environment, where U.S. forces only had tacit approval to operate in Syrian airspace. This was further complicated by Russia’s deployment of sophisticated surface-to-air missiles, which posed a potential threat to U.S. and partner aircraft.

Years of operations without any air-to-air engagements, and in which almost every weapon released was approved at a high level and scrutinized after the fact, had left U.S. pilots initially reluctant to act in self-defense against emerging threats. While there were several air-to-air incidents, including U.S. shootdowns of a Syrian Su-22 Fitter attack aircraft and two Iranian-made Shahed 129 unmanned aerial systems, these only occurred after senior U.S. commanders stressed the importance of self-defense and initiative to troops. U.S. forces have become accustomed to needing approval before acting, which was appropriate and needed to protect innocent civilians in counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations. But the flipside is that this may have instilled a hesitancy that a great-power adversary could exploit.

Because Russia and China both have extensive integrated air and missile defense systems and mobile air defenses organic to their maneuver units, the United States will not have air supremacy at the outset of a conflict. This means that U.S. strike aircraft will not be able to loiter over an area hunting for targets without assuming great risk, and accompanied by aircraft to defend them. These U.S. forces should be authorized and prepared to undertake defensive and offensive operations because they will likely be challenged by adversary air defenses and air forces. In future great-power conflict, U.S. military personnel will need to become more risk-acceptant and empowered to act without receiving explicit approval from their commanders. This is especially true in a degraded communications environment, as commanders may not be reachable to provide authorization.

Continued.....

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/IOLN2MP45RCVLDHI2OME7Z3FKI.jpg)